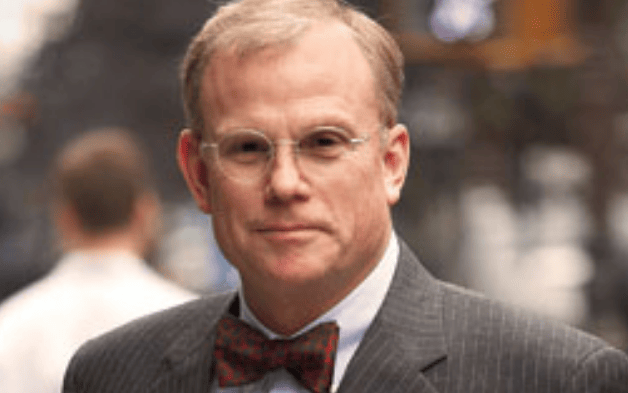

With the US-China trade war turning into what looks to be a grave and possibly permanent collapse in relations between the two super powers, institutional investors will reap their biggest gains from dislocation, according to Stephen Kotkin, professor of history and international affairs at Princeton.

The China investment challenge has always been to capture the aspirational middleclass. But while it is a great play for institutional investors, it’s limited in how many people have been able to pull it off, he said at a roundtable sponsored by Deerpath Capital Management.

“You have the aspirational middleclass on the one side of the investment and then hedging against massive dislocation on the other side,” he said.

“The big money that’s going to be made in China is going to be made from the dislocation, that’s the real big money.”

Speaking on the impact of a deepening trade war on asset prices, the Princeton historian said “That’s the one [geopolitical risk] we’re talking about today. Because the destructive potential is so vast, you can’t put a price on it.”

Kotkin warned that the trade war is part of a larger strategy by the US to destabilise the Chinese communist regime, adding that the belated confrontation with China will continue well after any trade deal is signed. “This is permanent now,” he said.

A burning issue for the US is the universally-held view that China would integrate into the US-led global order and look more like a developed democracy.

The academic said this is wishful thinking as China has no intention of opening up its political system.

However, he noted the panic this realisation has caused, prompting the Trump administration to demand a reset of the US-China relationship.

“The Trump administration achieved a total transformation of the conversation in the US by turning China into an adversary that must be confronted,” he said.

“He’s done it in his clumsy way and he’s not fully aware… but he’s done it.”

A suicide mission!

Kotkin, a renowned specialist in communist regimes, pointed out that Trump has decided to test the resilience of the Chinese communist regime.

“This is why the market doesn’t understand what to do. It hasn’t really understood Trump from the beginning and the risk that Trump could cause a meaningful shock.”

“On the other hand, who’s to say that China is really as strong as we think it is,” he argued, adding that despite breath-taking economic innovation, Beijing doesn’t act confidently.”

Investors at the roundtable were keen to hear more from Kotkin about how the fractious relationship between the world’s two biggest economies will play out and how robust the communist regime truly is.

In his view, the China challenge will remain even if the current regime collapses, since it would inevitably be replaced by a nationalist, potentially xenophobic right-wing authoritarian regime.

“Every time communism has tried to liberalise and open up, it’s liquidated itself. Those people who expected the Chinese communist regime to fully liberalise and to transform itself into a democracy or rule of order didn’t study communist history.”

Critically, he added, Xi Jinping won’t allow communism to be destroyed as it was in the Soviet Union.

“We’re looking for them to open things up politically and legally and if they do so they’ve destroyed themselves, it’s a suicide mission. So, the likelihood of that happening is low in my opinion.”

Kotkin also told the investors that the west can’t rise to the China challenge by crying foul or by punishing; it can only rise up to the task by competing effectively and responsibly.

“We don’t see that right now; we see the opposite on almost all fronts. Trump is confrontational but not competitive.”

Gary Gabriel, the CIO of State Super, asked about the chances of the two countries forging a good trade deal. Like his peers, Gabriel was keen to know the inside story – whether the two super powers are trying to get more favourable terms or whether they plan to overturn the current order.

Although China is a clear beneficiary of the US–led international order, Kotkin conceded it is hard to tell.

“There’s arguments inside US intelligence agencies on this point, there’s no consensus and that’s because inside China, there’s also no consensus on this question. They’re debating it themselves but the answers are very different.

“There are a large interest groups pushing to overturn and there are large interest groups pushing for the deal. So that’s why it tugs back and forth.”

Out of options

The Princeton scholar’s bottom line is that China’s power has to be accommodated in some fashion and that is problematic for the US because it will have to offer concessions.

Yet, on issues like Taiwan – and any moves towards formal independence –there’s no middle ground, he said.

“It’s unlikely the US will walk away from the South China Sea.”

Notably, at the worst possible time, mainland China has introduced the possibility of an extradition law for Hong Kong which means that anybody arrested in there can be extradited to Beijing.

What adds to investor turmoil, Kotkin warned, is that the China watchers, on both sides of the fence, don’t know the answer because the actors themselves don’t know the answers.

For Kotkin, the far bigger problem is that efforts to manage the prolonged stand-off are not working. To the US, China looks like the big malefactor and to China the US looks like the bully.

Richard Batey senior manager, macro strategy, investments, at AustralianSuper and Nader Naeimi, head of dynamic markets and senior portfolio management at AMP Capital, were keen to know if punishing China with a trade war would raise the risk of a serious political conflict. Both noted China’s heightened power in south-east Asia.

Kotkin spoke of the arrogance displayed by the Chinese authorities but said Beijing failed to back that up with the confidence required for a serious military confrontation.

“That tells you that there are limits to how confrontational the Chinese are going to get vis-à-vis the US. So, the Chinese have some options but those are not the same options as a confident power would have.”

Participants then discussed how much China had to lose by risking serious conflict – especially given China’s success – which set it apart from Russia and Iran.

A direct conflict would increase the risk of the regime collapsing, argued David Macri, CIO, at Australian Ethical. Consequently, given the US muscle, his feeling is that a deal is likely on terms favourable to the US”

Tim Macready, CIO of Christian Super, remarked that despite President Xi’s move to consolidate the power and lengthen his own political lifespan, there comes a date when that ends either because of internal forces or his death.

Mark Burgess, chair of HESTA’s investment committee, weighed into the debate by saying investors needed to consider that the damaged relationship between US-China has become a populist theme.

In his view, the now bipartisan issue could become so embedded in the US-Chinese psyche that politicians on all sides will play this theme for a long time.

Noting that all populists tend to find a thread of something that resonates, he likened this to opening pandora’s box.

“If I was the Chinese, I’d be worried about this because it gives enough momentum inside the system for them to effectively become a replacement, say, for Russia.”

Returning to an earlier theme, Kotkin said geopolitics, generally speaking, has very little importance for investors.

“However, he added, when great powers confront each other that’s not day-to day politics. “That’s world-shattering potential, although not world shattering inevitable.

The historian then steered the conversation back to Beijing’s long-term political strategy.

In the event of a trade deal, he went on to say, the big question for investors is whether they can trust that deal to hold for two years, five years, 10 years, 20 years.

“The problem is the uncertainty over this relationship is now semi-permanent. Even though there are calculations that can help reduce risks in the short term, it is really hard for long term investors; it’s a different environment entirely.”

Deerpath Capital founder, James Kirby, from picked up this point, arguing that the direct effect of further trade tariffs or prolonged conflict will be negative which raises some interesting decisions on what discount rate to use when evaluating new projects. A higher cost of capital, in turn, has the effect of reducing investments,’ Kirby said.

“I think that’s a real issue today and it’s going to continue until people feel like this high level of geopolitical uncertainty has been somewhat resolved.”

His comments were echoed by Mark Walker, CIO of UK’s Coal Pension Trustee Services, who also raised the topic of the strength of the US dollar versus the renminbi.

“Is this entire part of the world going to end up trading in renminbi,” queried Walker. Is it a financial weapon or not?”

Kotkin downplayed this by underlining the depth of the US capital markets. He expects more trade in Chinese currency, especially bilaterally, but no change of the international financial system as a result.

Brendan Hallet, from New South Wales Treasury Corporation, expects financial market volatility to pick up as political uncertainty grows and becomes more mainstream,

The roundtable concluded that geopolitics is very hard to build into investment portfolios and it doesn’t matter until it does and at which stage it is too late.