As NZ Super nuts out growing pains in processes and technology, it has made some recent decisions to change its governance route. Among them is the appointment of two co-CIOs who will lead the investment team together with collaborative decision-making and shared accountability. In a wide-ranging interview, co-CIOs Brad Dunstan and Will Goodwin tell Top1000funds.com about the fund’s “co-delegation” model, how its total portfolio approach will evolve under their leadership, and where it is hunting for new alpha sources.

New Zealand Super has long been touted as a fund with best-practice governance and recognised globally as a strong and transparent investor. But with only 24 years under its belt, it is still a young organisation. As it nuts out growing pains in processes and technology, the fund has made some recent decisions to change its governance route.

One of those changes is the appointment of dual decision-makers at the top of the investment team, with Brad Dunstan and Will Goodwin appointed co-chief investment officers in December 2024, which transitioned the fund to a “co-delegation” model defined by collaborative investment decision-making and shared accountability.

“It’s a little bit in vogue,” Goodwin says in a wide-ranging interview with Top1000funds.com, citing Canada’s OTPP and the Netherlands’ APG, which both have a co-CIO structure.

For functional reporting lines, Dunstan heads up the public markets, internal active strategies such as strategic tilting, and implementation and rebalancing, while Goodwin’s responsibilities include private markets, external mandates, direct investments, and the data analytics team.

It is a change initiated by chief executive Jo Townsend, who has been in the role since April 2024, to ensure a diversity of investment opinions on the senior leadership level, rather than a single dominant voice.

“We do have separate sets of delegations, and there are operations that I don’t need to be across, if he’s doing a large rebalance or some repositioning in the strategic tilting program [for example]. And likewise, he doesn’t need to be aware of what appointed managers are doing,” Goodwin says.

Where the dual decision-making kicks in is with decisions around new manager appointments or large transactions. Goodwin says that is when both CIOs are involved from the first screen, through the confirmatory due diligence, and the final tick of approval.

“It’s a model of being aware and being sufficiently involved across the whole portfolio but also keeping the right level of separation of power,” Goodwin says.

It’s when there is a difference of opinion that the rubber hits the road, and one thing that both CIOs agree on is that when there is a difference of opinion, compromise is not always the best outcome.

The CIOs are supported by contributions from the investment committee and other senior professionals, but ultimately if they can’t agree, “we do not progress”, Goodwin says.

“We spend a lot of time communicating what we’re doing and hopefully giving the team confidence. But it’s important that they know as well that they can’t just – I’m not saying they would – curry favour with one of the CIOs and the other one will just have to suck it up,” he says.

When disagreements arise, it’s all about having a frank conversation with each other, says Dunstan, because “agreeing not to do something is equally a decision as doing something”.

“You actually have someone there to bounce ideas with… we get some pretty robust discussions, but I feel we get better decisions,” he says.

Rapid growth

The fast growth of NZ Super, with assets under management forecast to double every eight to 10 years, means a need to scale up its investment capabilities. However, Dunstan says the fund is not going on a hiring spree to expand its 79-person investment team anytime soon.

“[We want to] make sure that the team doesn’t necessarily have to grow because the fund grows, so we are setting ourselves up to be more scalable than we have been previously,” he says, adding that the fund already has systematised and automated workflows in many public markets active strategies, from trade execution and settlement to portfolio construction.

Another challenge that comes with growth is the need to evolve its TPA framework. The fund practices what both CIOs call “one of the purest forms” of TPA, which is defined by an unrelenting focus on total fund outcomes, integrated decision-making, more dynamic portfolio adjustments, and risk factor exposures.

Being nimble and agile hasn’t been an issue when NZ Super was a small fund, but now it needs to have a more “pragmatic” mindset, Dunstan says.

“A pure TPA model means that if we don’t like real estate, we’re going to own none of that… You could also have a whole lot of real estate in your portfolio, and if you think real estate is a poor investment going forward, you could sell it all,” he explains.

“When you’re $200 billion, you can’t really say, I’m going to have $15 billion worth of real estate and no real estate team, and firing and hiring people every five years as markets move around.”

New alpha

Goodwin sees the diversification of alpha sources as a priority to evolve the TPA under the co-CIO leadership. Strategic tilting, which has been the fund’s biggest value-add driver over the past decade, will remain a cornerstone. But NZ Super is seeking to strengthen four other active risk pillars: beta implementation, internal credit strategies, real assets, and private equity and other alternatives.

“If you look over the last couple of decades, a lot of larger funds than us have had strong success in infrastructure. We’ve been relatively underweight infrastructure, that’s fine, it doesn’t suit our portfolio, and we actually haven’t suffered,” he says.

“But you also have to be aware of if we missed something… so making sure the team is thinking about that and not just resting on our laurels is really important.”

NZ Super has added 1.57 per cent alpha per annum and returned 9.92 per annum in the past two decades, according to its annual results as at June 30, 2025. Reflecting its focus on the long term, it uniquely reports on a 20-year moving average time frame.

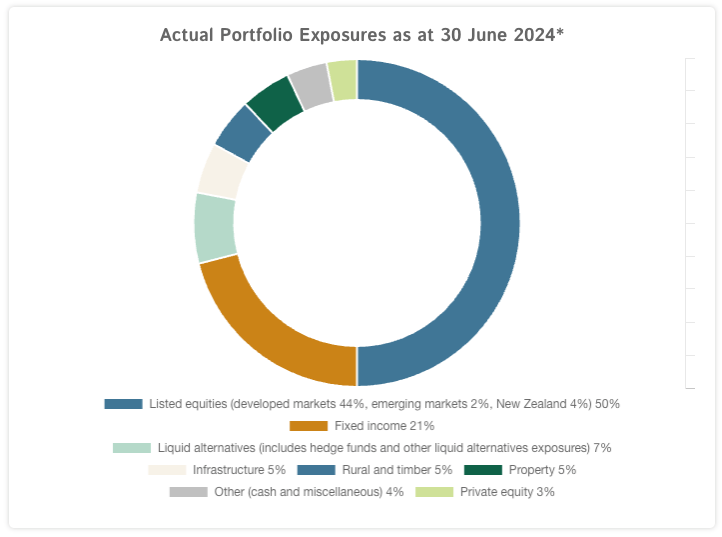

The fund doesn’t disclose its actual portfolio exposures until its annual report gets published in October, but a spokesperson confirmed the fund had increased its listed equity exposure by 4 per cent since June 30, 2024, with fixed income declining slightly and all other asset classes steady.

Within strategic tilting, Dunstan says while the model has stayed consistent in the past five or six years, the assumptions that feed into the model, such as different currencies’ risk premia, are constantly reviewed.

“The model evolves, but not a huge amount of new [long-term valuation] signals go in. It’s more scrutiny of the data and the assumptions around the existing signals… We will review the assumptions every two years,” he says.

“The program is systematic and we don’t want to be worried about and responding to short-term volatility, because it undermines the whole basis on which the program is built,” Goodwin adds. “We want to harvest the volatility and trade off it, but not seek to change our fair value, unless something material has happened.”

In preparing for a more complicated investment environment ahead, Dunstan says NZ Super will “prioritise what’s important to us”, including understanding macro factors and weatherproofing its portfolio accordingly, as well as adhering to its sustainability roadmap.

“[These include understanding] how the world is changing, how we model the world, and these linkages between, say, inflation and interest rates, and do we still believe in those going forward,” he says.

“Having a really good understanding of how our portfolio reacts in different environments will be important.”