Markets could get bumpy as monetary policy normalises, and as the pandemic’s destabilising impacts continue to ripple through the global economy. Philip Saunders and Sahil Mahtani explore the investment outlook across asset classes and regions.

The fast view

- Markets face a potentially difficult transition as monetary policy is normalised.

- Consider hedging against the risk that inflation moves higher than policymakers anticipate. Duration should be kept short.

- For defensive diversification, rather than traditional government bonds, consider cash, creditor-nation currencies and US dollars.

- Consider also shifting away from parts of the market that have done well since the Global Financial Crisis, like growth equities. The equities of companies with pricing power, and that start with reasonable valuations, are best placed if prices continue rising.

- Volatility may provide the chance to add exposure to longer-term thematic opportunities, such as those analysed in our Road to 2030 research project.

Global Outlook: Q&A with Philip Saunders

Philip Saunders, Co-Head of Multi-Asset Growth, assesses the outlook for global markets in 2022.

Date published: 23 November 2021

Authors:

Philip Saunders, Co-Head of Global Multi-Asset Growth

Sahil Mantini, Strategist, Investment Institute

01 Macro background: prepare for re-entry

Key points: The transition to normalised monetary policy makes the macroeconomic outlook uncertain. However, vaccine roll-outs should help underpin growth in 2022. China’s new willingness to tolerate weaker growth in the near term will weigh on regions that rely heavily on Chinese demand, like Europe. In contrast, the US is well positioned to sustain above-trend growth in 2022.

As every astronaut knows, re-entry can be the most dangerous part of a mission. Financial ‘normalisation’ – central banks’ return to conventional monetary policy after years of abnormally accommodative stances – may be a similarly difficult transition, potentially exposing markets to significant stresses in the year ahead.

But it was business as usual in 2021 from a policy perspective, with Western central banks sticking with super-easy policies. This was accompanied by a continuation of the ‘V-shaped’ recovery in markets and economies, despite some setbacks caused by new variants of COVID-19.

However, the dramatic recovery in demand has not been accompanied by an ability to supply it. Supply-chain disruptions have led to bottlenecks and sharply rising prices in many areas. Indeed, concern about inflation intensified as 2021 progressed, with market participants beginning to doubt that the surge in prices would prove as ‘transitory’ as the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and other central banks had suggested.

Inflation matters

Why the concern? The path of inflation matters because valuations across the asset-class spectrum assume a continuation of low real and nominal interest rates. After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, central banks were able to inject huge amounts of liquidity – often via unorthodox policies – without an inflationary backlash. The monetary and fiscal response to the COVID crisis has been on an altogether larger scale, and the impact in terms of asset-price inflation and cryptocurrencies is plain to see. But will central banks avoid having to tighten policy materially, deliberately weakening growth and causing asset prices to fall sharply, to prevent inflation expectations from becoming unanchored?

Vaccines may provide a shot in the arm

That’s not yet clear. At least we now have much better visibility on the process of social normalisation after the pandemic. We understand the disease now. And whereas zero-interest-rate policies persisted in 2021, ‘zero-COVID’ policies have been jettisoned – China being a notable hold-out – as it has become apparent that we are going to have to live with COVID and put our faith in mass vaccination. As immunisation programmes are rolled out more broadly, the world is opening up. This should underpin growth in 2022, especially in developing economies, many of which have so far lacked access to vaccines.

Monetary normalisation

The normalisation of monetary conditions, and the move away from zero-interest-rate policies, are yet to begin in earnest in the developed world. This is likely to add significant uncertainty throughout the year ahead. The Fed has already signalled its intention to taper its asset-purchase programme and end it by mid-year. It remains to be seen how other major developed-economy central banks will act.

In much of the emerging world, short-term interest rates have already begun to rise. But China has pursued a different course. It didn’t suffer as much from COVID-19 as other economies, due to its aggressive lockdown policy. So rather than quantitative easing, it deployed more conventional monetary, credit and fiscal measures. This mirrored the mini-cycles of Chinese policy loosening and tightening that characterised the post-GFC period.

A difference on this occasion is that policy tightening was initiated quicker and accompanied by more assertive macro-prudential policies, particularly in the property market. Chinese policymakers have evidently chosen to ‘fix the roof while the sun is shining’, using a positive growth environment and a surge in exports to introduce some potentially very significant policy adjustments.

China’s policy pivots

We refer to these policy shifts as China’s ‘five pivots’, and they represent the roll-out of President Xi’s policy priorities in the run-up to the twentieth Party Congress (scheduled for autumn 2022), at which he is likely to formally claim a third term as the General Secretary of the Party. State control is effectively being used to both reinforce and channel social and economic reform. The five pivots are:

- Curbing financial risks: This pivot led to the deleveraging campaign in 2018. It is also behind Beijing’s crackdown in recent years on shadow banking, local-government debt, peer-to-peer lending, cryptocurrencies and the caps on the leverage ratio for property developers.

- National security and self-sufficiency: The push on this front is captured by the catchphrase ‘dual circulation’, which refers to the goal of increasing reliance on the domestic cycle of production, distribution and consumption to drive China’s economy, rather than overseas markets and technologies. It is also reflected in the intense focus on technological independence and energy self-sufficiency.

- Anti-monopoly and regulation: 2021 has turned out to be a year of regulation. This pivot has led to crackdowns in various areas, such as education and the internet.

- Environment: This pivot gained notable momentum in September 2020, when President Xi said for the first time that China aims to achieve peak carbon by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

- Income/wealth distribution: The push on this front is captured by the term ‘common prosperity’. More specifically, the main theme here is ‘common prosperity for all and more equal wealth distribution’.

Clearly, the reaction functions of Chinese policymakers are changing in a material way. What is new is a willingness to allow growth rates to moderate in the medium term in pursuit of longer-term goals. They have been faster to tighten policy in this cycle and will probably be slower to loosen it than the consensus has been expecting. We believe that any significant loosening of policy is likely to begin in the first half of next year. However, the full impact of the prior policy tightening – which began in early 2021 – is now likely to be felt in the form of weaker domestic growth and in regions where there is a high dependence on Chinese demand. The latter include Europe, where that linkage is still not fully understood by market participants.

US growth will set the tone for tighter liquidity conditions globally

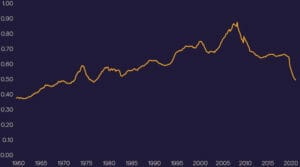

In contrast, the US is well positioned to sustain above-trend growth over 2022, even as growth in China and the eurozone slows. The US economy is relatively self-contained; consumers and corporates are flush with cash; banks are ‘under-lent’ (Figure 1); and supply constraints should gradually ease. Monetary conditions are also set to diverge, with the US finally moving to normalise monetary conditions while Europe remains stuck on hold and China eases.

In aggregate, given the continued dominance of the US in the global financial system, financial conditions overall will tighten, representing a material headwind for international markets. Financial normalisation – against a background of growth and policy divergence, and the distinct possibility of US inflation pressures persisting – is unlikely to be without bumps in the road, especially given elevated valuations across the asset-class spectrum.

Figure 1: US banks are ‘under-lent’

Ratio of US commercial bank loans to US money supply

Source: Richard Bernstein Advisors, Bloomberg, October 2021

02 Developed market government bonds: bumps ahead

Key points: Global liquidity conditions are likely to tighten internationally. Developed government bonds are expensive, and prospective longer-term real returns are poor given the interest-rate outlook.

We are already on notice that quantitative easing in the US will be tapered, and in all probability ended by June 2022 if not earlier. This will pave the way for increases in official interest rates. Our central case is that, although supply constraints should progressively moderate, price pressures are likely to remain uncomfortable for longer. This will force the Fed to normalise financial conditions more rapidly. Real rates will have to adjust from the current negative levels, and we ascribe a low probability to this being a smooth process.

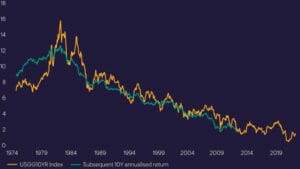

The withdrawal of asset purchases – which have been running at about US$120 billion a month as part of the Fed’s response to the COVID crisis – implies a reset along the yield curve to the natural market-clearing levels. The Fed now owns over 54% of 10-20 year maturity treasuries, the buying of which has had the deliberate effect of suppressing long-term interest rates. As things stand, bonds are at historically expensive valuations, and prospective longer-term real returns are poor under most scenarios (Figure 2). The combination of firm economic growth and the removal of the Fed’s support suggests higher long-maturity US Treasury bond yields.

Although short-term interest rates diverge between countries, developed government bond markets tend to be highly correlated beyond maturities of about five years, with the US Treasury market setting the tone. So we can expect liquidity conditions to tighten internationally.

Figure 2: Future returns on US government bonds look weak

Current 10-year yields and subsequent 10-year total returns on US government bonds (1-10 years) (%)

Source: Bloomberg, October 2021

03 Currencies: back the greenback

Key points: The US dollar has the potential to extend its rally in 2022. In contrast, Chinese policymakers are likely to let the renminbi weaken. Tighter international liquidity conditions may weigh on emerging market currencies, particularly the major debtor nations.

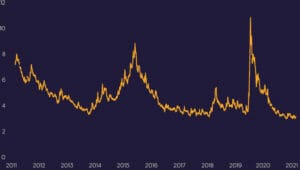

The US dollar didn’t weaken to anything like the extent many commentators were expecting in 2021. Although the greenback is expensive on valuation grounds, it remains well below its pre-COVID levels (Figure 3). With growth and monetary policy set to diverge materially in 2022, the US dollar has the potential to extend its rally. Real interest rates should rise in absolute and relative terms, and returns on capital in the US should continue to act as a magnet for global capital. True, the US current-account deficit is likely to widen to record levels in these circumstances, which could eventually become problematic, but the correlation between current-account deficits and US-dollar weakness has generally been low.

We expect weaker growth to limit the eurozone’s ability to follow the US along the path of financial normalisation. Meanwhile, Chinese policymakers are likely to respond to emerging economic weakness by allowing the renminbi to weaken, as will probably be the case for currencies elsewhere in Asia. A stronger US dollar suggests tighter international liquidity conditions, which in turn is not supportive of emerging market currencies generally, and particularly those of the major debtor nations.

Finally, the Japanese yen is cheap. While monetary conditions in Japan are unlikely to tighten much, as a creditor-nation currency, the yen remains an attractive source of defensive exposure versus European currencies in the event of a more severe general market set-back.

Figure 3: The US dollar is below its pre-COVID level

Trade-weighted US dollar index

Source: Visual Capitalist, 2019. Please note that this figure has been redrawn by Ninety One.

04 Credit: will the fallen angels rise?

Key points: Tighter monetary policy and higher US Treasury yields will be headwinds for credit markets where credit spreads are at historic lows, but default rates should stay low and rating upgrades should continue. This may especially benefit credits downgraded during the pandemic. Investors should expect more dispersion in performance as inflationary pressures and supply-chain disruptions impact sectors in different ways.

Credit spreads reached new lows in 2021, due to a combination of positive economic momentum and supportive market technicals. In 2022, tighter monetary conditions and higher US Treasury yields are likely to be headwinds for credit, resulting in an asymmetric risk profile for the asset class. However, other credit-market fundamentals should remain broadly supportive. Default rates should be pegged close to historical lows in developed markets and rating upgrades should continue, particularly for those names downgraded during the pandemic. Indeed, many of the ‘fallen angels’ of 2020 have the potential to be the rising stars of 2022. Finally, market technicals should remain relatively balanced, with supply moderating from high levels.

Importantly, we expect dispersion in credit markets to increase from record lows, particularly as inflationary pressures, supply-chain disruptions and labour shortages create headwinds for certain sectors. With minimal scope for further credit-spread compression, credit selection will be key in 2022. Resilient carry ideas are likely to be the sweet spot, offering a balance of attractive returns while providing good downside protection should market volatility resurface. Accordingly, we continue to see value in areas such as structured credit, loans and select parts of the high-yield market.

Figure 4: Credit spreads are at historic lows

ICE BofA US High-Yield Index option-adjusted spread (%; not seasonally adjusted)

Source: US Federal Reserve, October 2021

05 Emerging markets: strong foundation, despite headwinds

Key points: Emerging markets are in a relatively strong position, and growth in 2022 should be supported by the continued reopening of economies. However, less accommodative financial conditions and weaker Chinese growth will be material headwinds.

Emerging markets face two major headwinds: tighter global financial conditions and weaker Chinese growth. However, emerging economies are in a better position to deal with rising global interest rates relative to 2013 and 2018. This is because most of them have already raised domestic rates, reflecting greater caution about inflation risks than policymakers in developed economies.

Combined with favourable inflationary base effects, this has given emerging markets a real-interest-rate buffer against higher global rates. In addition, emerging market growth will be supported by a continued re-opening of economies, the return of tourism, increased private capital expenditure and the restocking of goods. Finally, external imbalances – historically the Achilles’ heel of many emerging economies – are much less prevalent, especially as terms of trade have remained very supportive.

Weaker Chinese growth threatens to reduce demand sharply for raw materials and it introduces a high degree of uncertainty to the outlook. This may be a significant overhang for emerging market debt and currencies in the first half of 2022, with the potential to drive emerging market risk premia higher. But we will learn more about the magnitude of the downturn, and the Chinese policy response to it, as the year progresses. China has considerable scope to ease policy to support growth, but, given Beijing’s new priorities, it is unlikely that the response will match Chinese authorities’ actions in 2008/9, 2011 and 2015.

The year ahead will also feature some political uncertainty, with presidential elections in Brazil, Colombia and the Philippines. All of them could result in significant changes in policy. Finally, in 2022 we expect that the recent trends towards environmental, social & governance (ESG) and ESG-related investment will continue to gather pace. ‘That carries with it both opportunities and risks, as investors become increasingly discerning about countries’ policies and frameworks (see Peter Eerdman’s outlook for the emerging market debt asset class. See also the emerging market regional outlook by Grant Webster and Archie Hart).

Figure 5: Emerging market rates have reacted to Fed messaging much more than developed market rates

1-year forward real policy rates (%)

Source: Bloomberg, October 2021

06 Equity markets: from heady cocktail to… hangover?

Key points: 2022 could be a more challenging year for developed equity markets. ‘Long-duration’ stocks are the most exposed, given the potential for higher interest rates. Regionally, US and European stocks are both expensive, but the latter are more exposed to growth risks. Asia ex-Japan equities are well into a de-rating process already, and pockets of long-term value have begun to emerge.

With liquidity tailwinds turning into headwinds, 2022 promises to be a more challenging year for developed equity markets. In 2021, a heady cocktail of low interest rates and continuing liquidity injections, coupled with high and rising margins and strong earnings, represented a perfect combination for the asset class. We now enter a period of heightened uncertainty.

In the US, the trajectory of financial normalisation is likely to be determined by the Fed’s need to keep inflation expectations from becoming unanchored – the more negative the inflation outcome, the faster the normalisation process will be and the greater the risk of policy mistakes.

Another inflation-related uncertainty is the impact of higher costs on corporate margins and earnings. History suggests that, so long as demand remains constructive, corporates should be able to pass on rising input costs, thus protecting margins. However, this will largely be contingent on current supply issues, which threaten to undermine the ability of companies to achieve sufficient operating leverage, being resolved quickly. Headline market valuations provide little in the way of a cushion. Long-term capital-market return assumptions have been driven down to levels that imply very modest future returns. However, intra-market valuation spreads remain wide, and as a result pockets of valuation opportunity remain, particularly among higher-quality companies with more modest top-line growth profiles. Selectivity will be key.

Set against these potential negatives, the risk of recession – the primary cause of bear markets – still seems remote. The US economy in particular appears primed for further expansion, even if supply constraints and spiking oil prices cause growth to decelerate in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022. Consumer and corporate balance sheets are strong and banks have considerable scope to re-leverage.

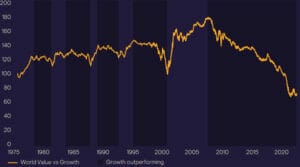

We are unconvinced that it is especially useful to talk in terms of the conventional equity style labels. But if we must, ‘long-duration’ stocks are evidently the most exposed. They have been the primary beneficiaries of declining interest rates in the period of so-called secular stagnation in the West, and their valuations are the most extended. Indeed, many ‘growth stocks’ in particular would appear to have been lifted excessively by the common tide (Figure 6). However transitory the current burst of inflation proves to be, our medium-term expectation is that the US inflation rate will be somewhat higher on average than it was in the post-GFC period. Real rates are set to rise quite materially and, as remarked on earlier, the removal of quantitative easing will free the longer end of the US yield curve to adjust. The best defence against the risk of inflation continues to be pricing power, the most valuable characteristic companies can possess in an inflationary environment, together with a reasonable starting valuation.

Figure 6: Growth has outperformed value since the GFC

Relative performance of MSCI Value Index vs. MSCI Growth Index (a down-sloping line indicates growth outperformance, and vice versa)

Source: Bloomberg, October 2021

It is probably too early in the current profit cycle to advocate conventional defensives. In any event, some of these assets are set to experience interest-rate headwinds if our central case is correct. In light of this, earnings disappointments are likely to be punished severely.

Regionally, although the US equity market is expensive by most measures, its higher level of self-sufficiency makes it less exposed to growth risks, particularly those posed by a weaker China. The US also contains the greatest concentration of companies with true pricing power. This is one of the reasons it has proven resilient, despite its seemingly high valuation relative to other regions, even as inflation expectations began to rise in the latter part of 2021. We are mindful that negative developments regarding US corporate taxes could cause a short-term set-back. However, they have not had a lasting impact on markets in the past.

Europe ex-UK equities are both trading on high valuations and more exposed to weaker Chinese demand. Quality European stocks with genuine sustainability credentials, a rare area of genuine European technological leadership, may be better placed than average to mitigate short-term cyclical headwinds. We believe allocating to them is likely to be a more fruitful strategy than buying European financials based on a rates view, as the required industry consolidation in European banks continues to be a story of hope rather than expectation.

In Asia ex-Japan, equities are already well into a de-rating process, reflecting the impact of Chinese tightening. What we lack is earnings visibility in the region, as well as clarity on Chinese monetary policy and the impact of the ‘five pivots’. Nevertheless, pockets of long-term value have begun to emerge, such as in the aggressively de-rated Chinese internet stocks. Even though the effects of China’s new policy priorities are yet to become fully apparent, the valuations of a number of stocks have moved way in excess of a reasonable assessment of the potential hit to profitability – suggesting this may be a good time to consider a modest reallocation to the area. The Chinese government is treading a fine line between respect for capitalism’s dynamism and innovation, maintaining an adequate level of control, and a genuine regard for consumer protection. We do not believe those who suggest this is the end of controlled capitalism as we have known it for 30+ years in China. Absent another more draconian round of regulatory tightening, we think the resultant increase in the cost of capital in this space may prove to be a positive development, squeezing out profitless growth companies with questionable business models. We advocate selectively building positions in cash-generative companies with proven business models that are not reliant on the liquidity environment to fund their growth. That said, we would caution against a wholesale shift into the space ahead of the demonstrable liquidity support that has tended to precipitate inflections in Chinese investor sentiment.

07 Commodities: a materially different environment

Key points: After surging materials prices in 2021, copper, nickel and iron ore appear most exposed to sharp corrections. However, commodity prices may settle higher than before the pandemic. Energy prices are likely to stay higher, at least through the winter. In an uncertain environment, gold stocks may be a useful diversifier.

The combination of abundant liquidity, a surge in demand and supply disruptions created an extraordinary environment for commodities in 2021, many of which experienced outsized price gains (Figure 7). All three of these drivers are set to moderate significantly in 2022. Within metals, copper, nickel and iron ore appear most exposed to sharp corrections, particularly given Chinese property-market weakness. There is a reasonable chance, however, that prices will settle at a higher floor than was the case pre-COVID. For steel and aluminium, the prospects look brighter in the Western world as China reduces exports to conserve power and reduce emissions.

Energy prices have also been on a tear, underpinned by severe demand and supply imbalances. Liquid natural gas prices jumped to new all-time highs in 2021, and energy prices will likely remain at higher levels through the winter season, especially if cold weather hits, but should settle down during the spring. However, oil prices could be boosted by increased transportation demand as air travel opens up, and because OPEC seems reluctant (perhaps unable) to increase production much faster. The continuing withdrawal of capital from the oil sector, driven by financial institutions’ climate-change priorities, threatens a disorderly energy transition over the medium term, with energy prices remaining high and displaying considerable volatility.

The path from here is uncertain and – with governments trying to normalise financial conditions and growth prospects diverging internationally – it remains challenging to forecast precisely what issues may arise in 2022. But it seems easier to forecast that there are likely to be issues. In such an environment, and with inflation pressures persisting, gold’s appeal should increase once again after a dull year for the precious metal. At current levels, gold-mining stocks look attractive on both valuation and fundamental grounds, and may be useful for investors looking to diversify their portfolios.

We would also highlight that efforts to tackle climate change will continue to be felt in commodity markets in 2022 and beyond. Much uncertainty persists about the pathway to net zero from here, but we know at least that decarbonisation will be mineral intensive, because the world is switching from a fossil fuel-based power system to one which is essentially metals-based. Wind turbines, for instance, are 70% steel, while copper is required to generate and carry the electricity. It adds up to a complex backdrop for materials markets. We believe there will be many opportunities for commodity investors as the energy transition progresses, but they will not always be obvious. And those looking to capture them need to be active and careful, because supply/demand balances are volatile and long-term structural themes will continue to crash into short-term stocking cycles.

Figure 7: Commodities have rarely been so expensive (though resources stocks are well below highs)

Prices of fossil fuels and metals/mined commodities as a percentage of global GDP

Source: Bernstein Research (based on BP Statistics, Bloomberg, IMF, Bernstein estimates (2021) and analysis), November 2021

08 Geopolitics: too much to lose

Key points: Geopolitical risk is a consideration for investors for the first time since the Cold War. However, we think China has everything to gain from playing a long game, which reduces the risk of major geopolitical flashpoints in 2022.

With the ‘Chimerica’ model broken and the Biden administration pursuing an aggressive policy to frustrate China’s rise, geopolitical risk is a consideration for investors for the first time since the Cold War. Where Biden’s approach differs from Trump’s is in the consistency with which it is being pursued. The effect of this has been to accelerate reform on a number of fronts in China, most notably in technological innovation and more generally in China’s pursuit of self-sufficiency in certain sectors. Investors have begun to mull a serious escalation of geopolitical tensions between the US and China as a rising tail risk. We beg to differ. Unlike during the Cold War, today’s global economy is highly inter-connected. China’s exports to the US are booming and US corporates have been notably slow to shift their supply chains away from China. China itself is addressing some very significant domestic structural challenges and seems to have everything to gain from playing a long game.

09 Road to 2030: evolution

Key points: One year into the new decade, we provide an update on Road to 2030, our project to analyse the major trends driving markets and investment outcomes. We discuss how our views have evolved on: the rise of China; climate change; technological disruption; debt; and demographics.

In Road to 2030, our thematic asset-allocation project which we shared for the first time last year, we set out what we think will be the major global trends driving markets and investment outcomes this decade. With one-tenth of the journey to 2030 now behind us, here is how our thinking regarding our five structural macro themes has evolved.

1. The rise of China: When we first looked at this theme, it was clear that China was undergoing three distinct transformations. First, a shift from fixed-asset investment to consumption; second, a shift up the value chain as China seeks technological independence in select areas; and third, China’s outward economic expansion. The US response to this, focused on security and competition, is a crucial overlay to the global impact of these transformations.

Since we launched Road to 2030, China’s move up the value chain has continued unabated, even sped up, as the vast funds (over US$1.5 trillion) China intends to direct towards investment in semiconductor technologies, among others, show (see our recent work with Professor Chris Miller on Chinese technology policy). Xi Jinping has continued to highlight China’s reliance on outside nations for certain core technologies as a vulnerability.

Meanwhile, China’s shift towards a consumption-based economy has arguably been postponed (Figure 8); at least, this is what the 14th Five Year-Plan (2021-2025) promises – to keep the portion of the economy devoted to investment and consumption roughly the same. The US response has taken a more strategic bent through the AUKUS submarine alliance, which has only become more relevant after China’s hypersonic missile test in October 2021. Within China, it is now clear that the main story is not economic reform or political control, but both. The big-picture goals are to improve the quality of life for China’s people, and establish a more centralised, national-security-directed state.

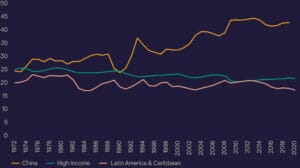

Figure 8: China’s investment spending is unlikely to pivot towards consumption in the near-term

Gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP)

Source: Bloomberg, October 2021

2. Climate change: The key distinction in the climate-change theme is between physical risks — changes to the planet — and transition risks as businesses and households alter their behaviours. Climate-change modelling is complex, but it is generally agreed that the main physical risks over the next decade are extreme weather events rather than permanent changes in the environment. Transition risks are therefore the key investment risk — and opportunity — until 2030.

Globally, annual spending on decarbonisation is still at least US$2 trillion short of that required (a gap the investment industry has a major role in closing). Efforts to address climate change have continued to gather momentum, with many more countries and companies adopting net-zero transition commitments and plans in 2021. But we still believe the world remains merely at the foothills of a multi-trillion dollar investment spree over the coming decades, and that there is a major opportunity for investors to both generate returns and make a meaningful contribution to tackling the climate problem. The key challenges are to avoid the public backlash against environmental spending that is occurring in some Western nations, as well as localised approaches to decarbonisation that further disadvantage the poorest countries.

3. Technological disruption: Our key insight here is that technology is not a sector, but an enabler for new and existing businesses. We have therefore divided this theme into five functional areas. First is better healthcare, by which we mean more preventive therapies and new, potentially cheaper, treatments. Second is the growing abundance of goods and services. Third is the shift to a more flexible workplace. Fourth are innovations in personal mobility. Finally, we believe states are going to take a much more activist stance on their economies.

Invention and innovation are two different things. Inventions can occur at any time, but periods when innovations on these inventions diffuse widely and lead to technological shifts occur only periodically. These periods of technological diffusion often require strong economic growth, since that is when businesses and governments are in a position, and have a need, to invest. Given current high rates of growth and the shortages in semiconductors and all manner of other materials and goods, we may be in just such a period. Businesses are actively looking for new technologies to reduce their cost bases, and there is talk of an uptick in productivity growth from the sluggish levels of the past decade. The recent success of Tesla, which is worth more than all the other companies in the auto sector (at the time of writing), shows that the same drivers of technological growth (data, network effects and so on) in one area become decisive in markets previously thought of as traditional. That is the definition of diffusion.

4. Debt: The last four decades have seen an explosion in public and private debt around the world, facilitated by declining real and nominal interest rates and latterly by quantitative easing. Unexpected events like COVID-19 have accelerated the debt build-up, and there has been a shift in the attitudes of policymakers towards using fiscal spending to address the energy transition and inequality. As a result, debt stabilisation has taken a backseat to other priorities, certainly relative to the 2010s when austerity measures were pursued by a number of countries.

Eventually, however, we think the fiscal measures put in place by the pandemic will seem disproportionate as the economy normalises, and a combination of measures are likely to be implemented to stabilise these high debt levels: financial repression; competitive devaluations to boost exports; more austerity and taxation; reform and growth; macroprudential policies; helicopter money; and private debt forgiveness. Stabilising debt has of course been nobody’s focus during the pandemic, and as a result debts have mounted. It will become clearer over the coming year what countries’ strategies are for stabilising debt levels.

5. Demographics: We have split this vast and important topic into the impact of demographic trends on government budgets, on GDP and some idiosyncratic effects. As people age, pension liabilities will increase, as will healthcare costs, squeezing non-welfare spending. Older people are likely to dominate the political agenda and new products will emerge to address old-age care.

Our thinking on this theme has not changed much. We are convinced that demographics are in general deflationary, though there are short periods when demographics can become marginally less deflationary — as we anticipate in the US over the coming decade, supporting the case for US outperformance. Budgets delivered over the last year have emphasised the new roles of security and welfare in state spending. For example, healthcare spending is now 40% of UK day-to-day spending, a figure that will continue to rise. COVID has brought working-age labour-force participation down, but of course it is expected to rise again as conditions normalise.

China’s recent census (preliminary results were released in May 2021) appears to have been a catalyst, at least in terms of timing, for a host of reforms to make it easier for families to have children, including curbs on video games, after-school tutoring and (crucially) high property prices. As Western countries deal with the challenges of mass migration and the decline of fertility rates, perhaps China’s solutions will come to be theirs as well.

10 Conclusions

Markets face a potentially difficult period of transition. Risk premia across asset classes currently build in little in the way of a buffer as we enter a period of considerable uncertainty.

It is possible that inflation fears will subside relatively quickly as actual and artificial shortages moderate – the cure for high prices is, after all, high prices. This would provide central banks with greater room for manoeuvre. But if inflation pressures prove to be more persistent, the risk of the Fed being exposed as ‘behind the curve’ (i.e., as raising rates more slowly than prices are rising) is considerable.

The good news is that the current growth and profits cycle has probably not run its course; the pool of unengaged liquidity on private-sector balance sheets is substantial; and the willingness of governments to increase fiscal spending, despite high debt levels, has undergone a notable transformation in response to the COVID shock. Spending on the energy transition and to address inequality are the common themes here.

What should investors do? As noted in the fast view, we suggest the following:

- There is a strong case for rebalancing strategic allocations away from parts of the market that have done well since the Global Financial Crisis, like growth equities.

- The equities of companies with pricing power, and that start with reasonable valuations, are best placed if prices continue rising. Duration should be kept short.

- There is a high probability that volatility will provide the chance to add exposure to longer-term thematic opportunities.

- While hedging against more negative inflation outcomes makes sense, it should be remembered that the prices of many real assets are a function of the same forces that have driven conventional financial assets to their current levels.

Specific risks

Currency exchange: Changes in the relative values of different currencies may adversely affect the value of investments and any related income. Derivatives: The use of derivatives is not intended to increase the overall level of risk. However, the use of derivatives may still lead to large changes in value and includes the potential for large financial loss. A counterparty to a derivative transaction may fail to meet its obligations which may also lead to a financial loss.

Equity investment: The value of equities (e.g. shares) and equity-related investments may vary according to company profits and future prospects as well as more general market factors. In the event of a company default (e.g. insolvency), the owners of their equity rank last in terms of any financial payment from that company. Emerging market (inc. China): These markets carry a higher risk of financial loss than more developed markets as they may have less developed legal, political, economic or other systems.

General risks

All investments carry the risk of capital loss. The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise and will be affected by changes in interest rates, currency fluctuations, general market conditions and other political, social and economic developments, as well as by specific matters relating to the assets in which the investment strategy invests. Environmental, social or governance related risk events or factors, if they occur, could cause a negative impact on the value of investments.

Important Information

This communication is provided for general information only should not be construed as advice.

All the information in is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete. The views are those of the contributor at the time of publication and do not necessary reflect those of Ninety One.

Any opinions stated are honestly held but are not guaranteed and should not be relied upon.

All rights reserved. Issued by Ninety One.