Who is racing ahead in the EV transition? Passenger cars have got a head start, but trucks – responsible for 8% of global GHG emissions – are key drivers in the journey to net zero.

How are winners emerging from the transition?

01 Riding electrification tailwinds

02 Policy catches up to the climate crisis

03 Going the distance: challenges facing the commercial EV transition

04 Is hydrogen the answer?

05 China leads the way in the electrification transition

06 Far reaching opportunities across the global universe

01 Riding electrification tailwinds

Collaboration is a key ingredient to success in the commercial EV transition.

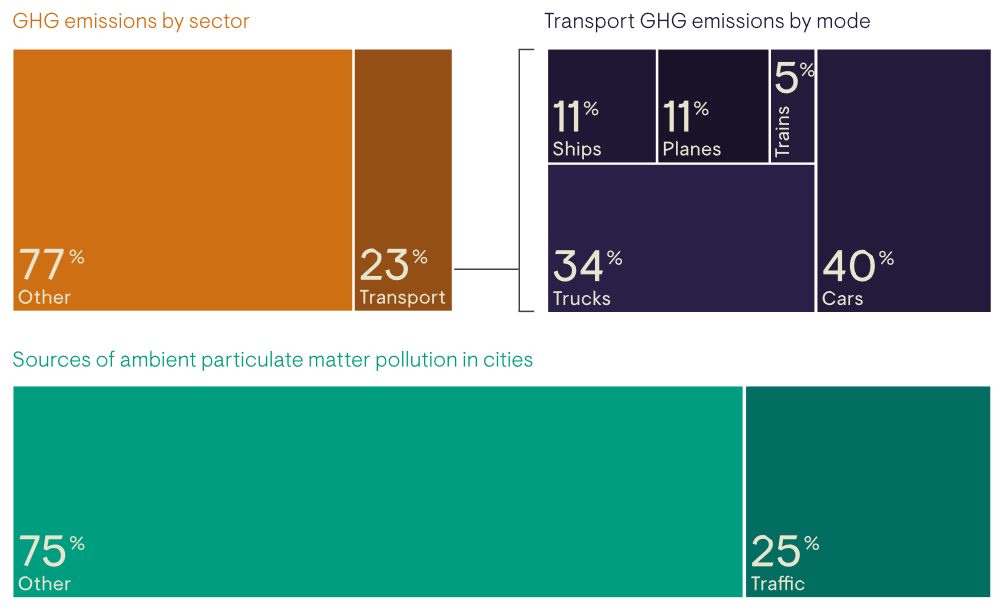

As the world moves towards a decarbonised future, the spotlight has centred on the electric car transition as the tangible evolution that will touch our everyday lives. However, it is often overlooked that commercial vehicles constitute the largest or second largest source of transport sector emissions in every major economy globally, according to the US Department of Energy. Trucks have a huge part to play, contributing around 8% of global GHG emissions (Figure 1). This is perhaps reflected in that trucking remains the dominant form of freight distribution in both the US (67% of the total) and the EU (75%)1 .

Figure 1: Trucks represent 8% of global GHG emissions

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, “Global Review of Vehicle Efficiency Standards”, 13th August 2019.

2020 marked a turning point for the industry, as the seven largest players in the European truck industry collaborated to announce that all new vehicle sales would be fossil-free by 2040. Broader adoption of battery-powered trucks is expected to become a reality in the near future, but other technologies are also being explored to achieve decarbonisation. Development of trucks powered by ‘green’ hydrogen – produced from renewables – is in its infancy, but it may provide a solution to decarbonise trucking before too long.

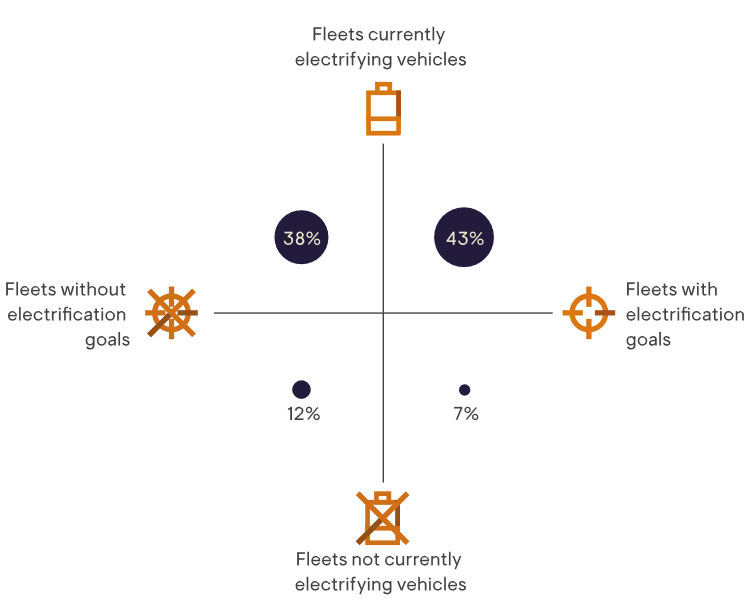

Looking at the nearer future, adoption of battery-powered electric vehicles is gathering pace. A recent survey of large commercial fleet owners in the US found that 81% were currently electrifying vehicles, while half of owners are pursuing explicit goals for EV adoption (Figure 2) . While individual order sizes remain small as customers adapt to the new technology, the next year or two could see significant progress towards mass production. Globally, multiple major OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) – such as Daimler, PACCAR and Volvo2 – have expanded their EV product lines and announced their intention to ramp up production of battery-run electric trucks through 2021 and 2022. Meanwhile, waiting in the wings are new entrants, such as Tesla and Hyliion, looking to grab market share from incumbents.

Figure 2: Fleet electrification goals and current EV adoption status

Note: Combined survey responses to the questions: “Does your organisation have an explicit goal for electrifying your fleet or reducing your fleet’s emissions?” and “Have you begun to transition any of your fleet vehicles to electric?”.

This graphic has been recreated by Ninety One.

Source: Lynn Daniels and Chris Nelder, “Steep Climb Ahead”, Rocky Mountain Institute, 2021.

However, disruption may not be a destructive force in the trucks industry. Rather than the margin-dilutive competition seen in the passenger auto sector, we believe that the trucking industry is adopting a collaborative approach to the EV transition. Participants are seeking a broad coalition (across both public and private sectors) to help spread the costs of the R&D and infrastructure build-out needed to accelerate adoption. Success in the commercial EV transition requires overcoming a different set of challenges from those facing passenger cars, such as customer acceptance, the creation of charging networks, servicing and so on. Collaboration between the biggest trucking participants makes overcoming such challenges more likely and importantly creates opportunities for investors in those companies that can race ahead in the EV transition.

1 Source: Eurostat, March 2020, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2019.

2 One of these stocks is held in 4Factor portfolios.

No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those achieved in the past, or that significant losses will be avoided.

This is not a buy, sell or hold recommendation for any particular security. For further information on specific portfolio names, please see the Important information section.

The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise.

02 Policy catches up to the climate crisis

While industry participants are collaborating, policy drivers give extra impetus to the decarbonisation transition.

The decarbonisation agenda has been propelled forward in Europe by the EU green stimulus package to aid the post pandemic recovery and reach the climate change objectives set out by the Paris Agreement. This includes the launch of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, which offers support for the provision of ‘recharge and refuel’ stations to promote clean technologies1. Europe’s turbocharged drive towards cleaner transportation is pertinent as transportation remains the only major economic sector in Europe in which emissions have increased since 19902.

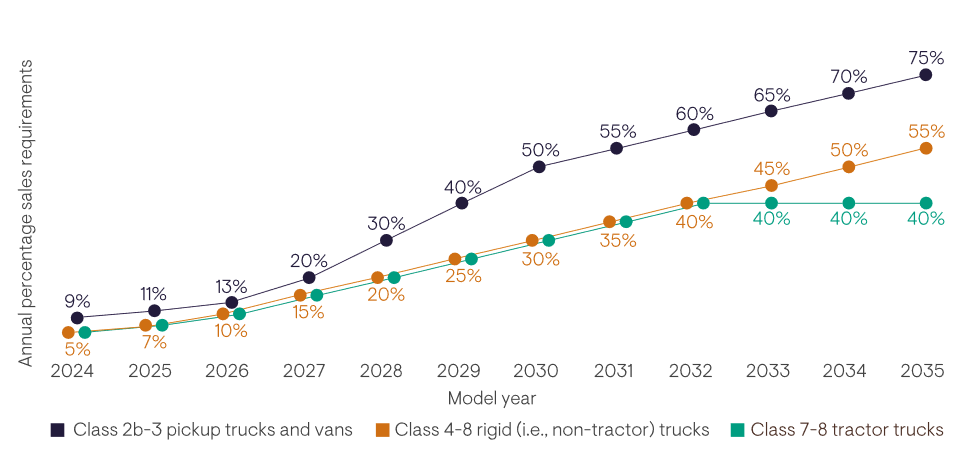

In the US, until recently most efforts to de-carbonise the trucking sector have been at state level. Last year, California adopted the ‘Advanced Clean Trucks’ rule, imposing mandated sales quotas for zero-emission trucks that manufacturers must meet from 2024 (Figure 1). A broader group of 15 states and Washington D.C. have pledged to make at least 30% of new medium- and heavy-duty truck sales zero emission by 2030 and 100% by 2050. The recent ‘American Jobs Plan’ unveiled by President Biden contains an eye-catching US$174 billion of investment in EVs. This includes plans to build a network of 500,000 chargers by 2030 and electrify the federal fleet, including the US Postal Service.

Figure 1: Phased mandated zero emissions sales quotas for manufacturers in California

Percentage schedule by vehicle group and model year

Source: International Council on Clean Transportation, July 2020.

1 Source: European Cluster Collaboration platform, “Flagship area: Recharge and Refuel”, 23 November 2020.

2 Source: European Environment Agency, data from May 2014 and December 2020.

The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise.

03 Going the distance: challenges facing the commercial EV transition

While destructive disruption characterised the passenger car electric transition, unique challenges for trucks are accompanied by distinct market characteristics.

We see a number of significant differences between the commercial and personal auto markets that will likely define the rate of EV adoption and the winners that emerge from the transition.

These are broadly that commercial vehicles:

- tend to have a greater focus on the economics of new truck purchases, with end-users taking into account the “total cost of ownership” (defined as the full cost of owning a vehicle, including initial purchase price, lifetime fuel costs, insurance, maintenance, and licensing).

- see much heavier day-to-day usage and thus buyers will have a preference for ‘tried and tested’ technology, typically waiting for millions of miles of testing prior to adoption.

- need a longer range and this is an important factor when assessing usage cases for commercial vehicles.

- require much more support, with uptime (time in use) a key determinant of fleet profitability. This necessitates extensive maintenance networks able to service vehicles.

The production of trucks also tends to differ from that of personal autos in that they are typically made to order, with far more customisable features (such as engine, transmission and weight distribution). Consequently, a much higher proportion of components will be supplied by third parties rather than being developed in-house. Therefore, companies’ own technology may not be key to defining the winners in the commercial EV transition. This reduces the risk of a squeeze on profits and cashflow from elevated investment in internal R&D, but it does introduce greater risks around product sourcing and supply chain concentration.

While there are challenges to overcome in the EV transition, distinct market characteristics have potential advantages for investors. Regional truck markets are relatively consolidated, with the EU, US, Indian and Chinese markets dominated by two to five players. Such companies have strong brand recognition and extensive service and maintenance networks that are difficult for new entrants to replicate. Market shares are relatively stable and competition on price is rare, which means less risk of disruption from new entrants and potential pressures on margins from price wars.

“Range anxiety” ramps up a gear

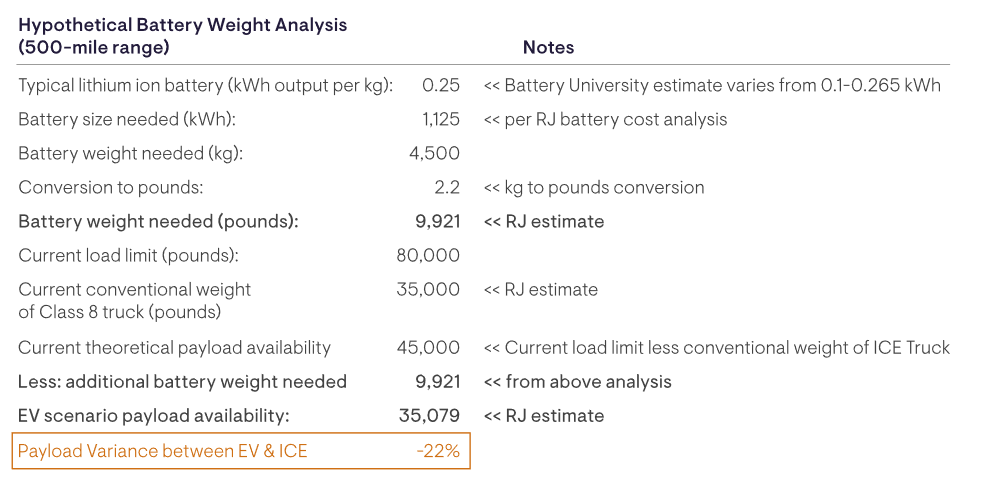

A challenge the personal and commercial auto sector share is “range anxiety”, but this is more complex for trucks. Current battery technology is not yet able to offer the 500-700 mile range required for long-haul trucking. While manufacturers can in theory extend range by stacking multiple batteries, weight then becomes the constraining factor. Based on current technology, US investment bank Raymond James estimates a battery weight of 10,000lbs would be needed to reach 500 miles of range, reducing the available commercial payload by over 20% versus a diesel engine (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Battery weight creates a payload challenge for EV trucks

Source: Battery University, Environmental Protection Agency, Raymond James (RJ) estimates, “Shifting Gears from Boom & Bust Pre-Buys to an Underlying Desire for New Equipment”, 20 November 2019. EV= electric vehicle. ICE= internal combustion engine.

Larger batteries require more powerful charging stations to keep charge times down. Truck stops and fleet yards that service Class 8 heavy-duty trucks1 require enough power supply for ultra-chargers of 1.7MW or more per charger, compared with most powerful direct current (DC) fast chargers currently available in the 350-500kw range2. Infrastructure needs to be expanded and upgraded to meet such high charging requirements. Some health regulations limit human interaction with high voltage electrical feeds, which makes the development of robotic charging infrastructure important.

Such substantial charging requirements could result in stresses to grid capacity. The reliability of charging infrastructure is crucial for commercial transportation, requiring large backup generators. To give some idea of the scale of the necessary potential build-out, there are currently only 5,000 DC fast-charging stations in the US out of a total of nearly 42,000 EV charging stations3. This compares with a Class 8 population of around 3.4 million4. While President Biden has pledged to build a network of 500,000 EV chargers by 2030, it is not yet clear what proportion would be suited to charging commercial vehicles. Collaborative efforts between governments and industry participants are key to overcoming challenges such as these.

1 Class 8 trucks are defined in the US as trucks over 33,000lbs in weight.

2 Source: Lynn Daniels and Chris Nelder, “Steep Climb Ahead”, Rocky Mountain Institute, 2021.

3 Source: Alternative Fuels Data Center, April 2021.

4 Source: truckinginfo.com, January 2019.

The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise.

04 Is hydrogen the answer?

Hydrogen could fuel our decarbonised future. How could such fuel-cell systems offer a solution for trucks?

Hydrogen fuel-cell systems may offer a solution to the potentially intractable battery-related issues for long-haul freight. Hydrogen truck manufacturer Nikola is targeting a 900-mile range for its Nikola Two model, with a full tank comparable in weight to diesel alternatives1. Filling up the tank should also be easier and safer than with battery electric alternatives, as surplus spillage turns to water.

Commercial hydrogen production is currently largely for non-transportation uses, such as ammonia production and oil refining. Around 95% is generated from natural gas and coal2, but hydrogen could eventually be a pollution-free energy source. Solar and wind power can be used in conjunction with electrolysers to create emission-free hydrogen (‘green’ hydrogen). Conversion of electricity to hydrogen could take place either off-site and be piped in, or via on-site electrolysers at the fuelling station (Figure 1).

Figure 1: From energy creation to energy consumption across the hydrogen value chain

Source: Nikola website, April 2021.

Significant investment in hydrogen fuel-cell development and the infrastructure required to power fleets will be needed over the coming decade. We are encouraged by signs that manufacturers are in many instances looking to adopt a collaborative approach to this investment, helping to spread the burden of significant upfront investment. Notable examples of JVs in fuel-cell development include Daimler-Volvo, Toyota-PACCAR and Nikola-Iveco. H2Accelerate, a collaboration between manufacturers (Daimler, Volvo and Iveco) and fuelling infrastructure providers (OMV and Shell)3 to support synchronised investments into hydrogen adoption was announced last year. A decade long rollout is expected to begin with groups of customers willing to make an early commitment to hydrogen-based trucking.

1 Source: Nikola, April 2021.

2 Source: International Renewable Energy Agency, “Hydrogen: A renewable energy perspective”, September 2019.

3 One of these stocks is held in 4Factor portfolios.

No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those achieved in the past, or that significant losses will be avoided.

This is not a buy, sell or hold recommendation for any particular security. For further information on specific portfolio names, please see the Important information section.

The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise.

05 China leads the way in the electrification transition

The global nature of decarbonisation efforts in transportation highlights the depth of this structural trend and why it’s key to take a global lens to investment opportunities.

Asian OEMs have a head-start on their Western peers when it comes to fuel-cell technology. Toyota delivered its first hydrogen-powered truck to the Port of Los Angeles in November 2019. Meanwhile, Hyundai delivered the first 50 trucks of a 1,600 truck order to customers in Switzerland last year.

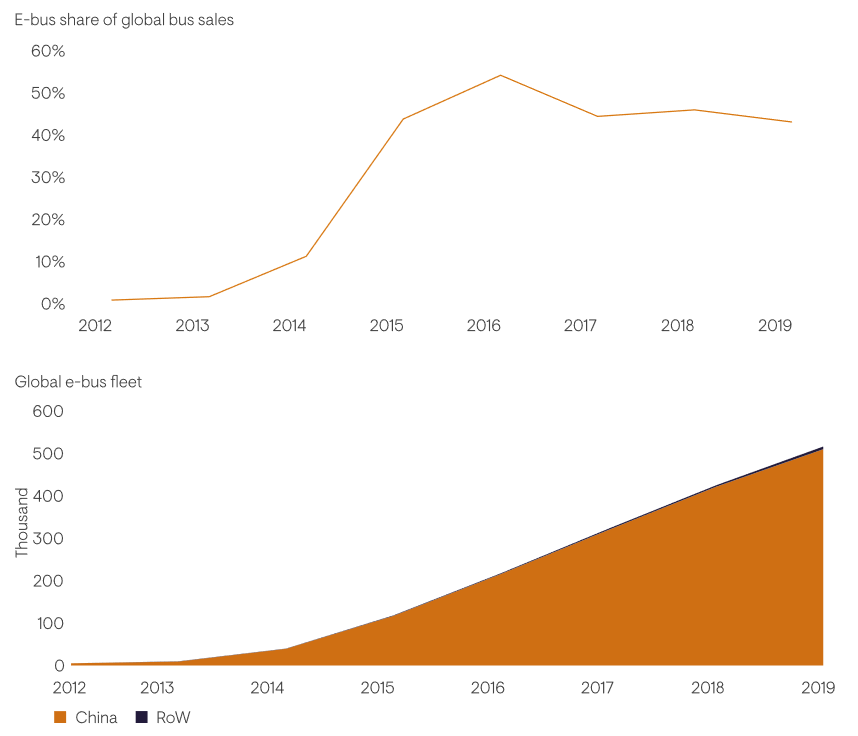

While broader Asia leads the way on hydrogen fuel-cell technology, China as the world’s largest auto market is well positioned for the EV transition, supported by government policy and declining battery costs. The global e-bus fleet has grown 93 times over seven years to over 516,000 in 2019 (Figure 1). The Chinese market is expected surpass the 1 million e-bus mark by 2023 and reach 1.3 million by 20251.

Figure 1: China dominates the electric bus market

Source: BNEF, Bloomberg Intelligence, “Electric Vehicle Outlook 2020, Bloomberg New Energy Finance”, 19th May 2020.

Outside of China, EV adoption is also expected to accelerate in the next decade. 26 major cities globally have now signed the ‘C40 Green and Healthy Streets and Clean Bus Declaration’, committing to procure only zero-emission buses from 2025. Multiple European cities have adopted or are trialling EV refuse trucks. Paris, for example, has had electric trucks since 2011. US municipalities have generally been slower to adopt EV in the absence of clear policy drivers towards this transition, but this is changing as discussed earlier, particularly with the support of the Biden administration.

The global nature of these efforts highlights the depth of this structural trend and why it’s key to take a global perspective when it comes to investment opportunities. While the urban transport of cities is becoming increasingly electric, similarly manufacturers are introducing electrification across their product chain to meet carbon-free goals and improve profitability.

1 Source: Wood Mackenzie, “The growing global e-bus landscape in China and beyond: E-bus and infrastructure forecast for China, Europe and the US”, 16 September 2019.

No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those achieved in the past, or that significant losses will be avoided.

This is not a buy, sell or hold recommendation for any particular security. For further information on specific portfolio names, please see the Important information section.

The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise.

Transition to ‘equipment as a service’

The shift to EV means truck manufacturers will increasingly be paid by distance travelled. Buying a truck outright is a significant capital expenditure (typically US$100-150,000 per truck), with demand levered into the economic cycle. Moving to an ‘equipment as a service’ model, could involve customers leasing the battery and charging infrastructure, while paying for certain services (such as driving and service & maintenance) on a per usage basis.

Truck manufacturers have historically traded at a discount to other industrials due to their elevated cyclicality. If they can smooth out their revenue stream by replacing a volatile capex cycle with more stable service revenues, we believe the market will reward them with higher earnings multiples. Such a transition can also increase customer “stickiness” as customer owners will become more tied to manufacturer battery/fuel-cell systems. More truck owners will take out extended service contracts with the manufacturer post the warranty period, especially as they will not have the in-house expertise to service the battery nor the company-specific software.

Volvo leads the way

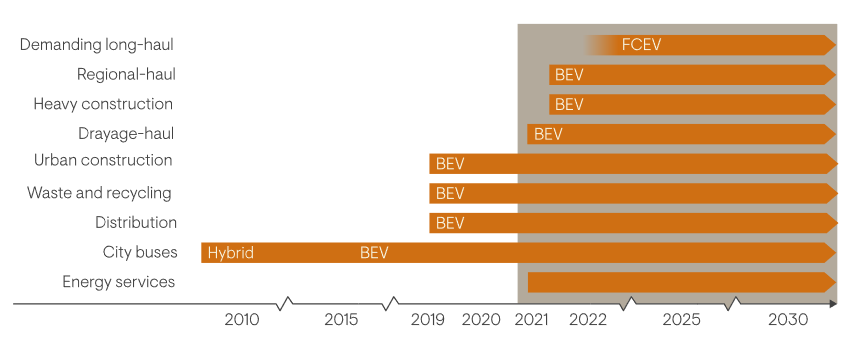

European manufacturer Volvo1 appears to be well-placed for success in the EV transition, with a major product rollout from this year to work towards its target of 100% fossil-free sales by 2040. It started with its buses over a decade ago and has filtered this through the product chain from electric refuse trucks to heavy-duty trucks and construction equipment. From this year onwards, Volvo Trucks will sell a complete range of battery-electric trucks in Europe for distribution, refuse, regional transport and urban construction operations.

Figure 1: Volvo’s timeline for its EV transition

Source: Volvo Capital Markets Day, November 2020. BEV= battery-electric vehicle. FCEV= fuel-cell electric vehicle.

The company sees a significant opportunity to increase profits from the transition to EV with revenue per vehicle expected to be 40-50% higher than on an ICE vehicle on similar margins. EV integration creates a potential step change in service contract penetration and elongates such contracts. By 2030, Volvo expects half of its revenues to be from services and solutions, increasing the stability of earnings. We think this could drive share price performance as investors ascribe a higher multiple to this earnings stream.

Far reaching opportunities across the global universe

The challenges that need to be overcome in order to succeed in the commercial EV transition, such as technology, infrastructure and higher refuelling/charging needs, translate into opportunities inside and outside of the industrials space. The manufacturers that collaborate to capture funding and drive change are better placed to succeed given the significant capital expenditure required to meet infrastructure requirements. A company’s ability to shift internal R&D spend to making the transition will be key, and collaboration on projects and outsourced component manufacturing facilitates this.

With European policy supportive of the evolution towards a greener continent, many of the secondary companies participating in this change are headquartered or listed in Europe. For example, Schneider Electric and Alfen provide electrical charging infrastructure, while Siemens has pioneered e-Highway technology in partnership with Scania2 for trucks to be hooked up to overhead electric rails in Germany. The use of hydrogen technology is at a nascent stage, limited to pilot projects mostly located in Europe, but spanning different industries. More traditional battery manufacturers are already participating heavily in the electric transition with increased appetite for their products. Wuxi Lead Intelligent Equipment1 is one example, as the lead supplier in EV battery equipment in China with close to 20% market share.

Opportunities for investors to gain exposure to the electrification transition in commercial transportation across sectors are emerging. For truck companies, the transition could evolve their business models to ‘equipment as a service’, creating more stable revenues and longer-term margin improvement, both share price catalysts. Given the push towards decarbonisation is a global phenomenon, we believe taking a global approach enables investors to capture the primary as well secondary winners of this structural transition. The ability to screen opportunities systematically, combined with in-depth fundamental research, allows the 4Factor process to seek out the potential winners and exploit opportunities. We believe those companies with flexible business models, strong financial positions and innovative strategies are best placed to succeed.

Important Information & Disclosures

General risks. The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise. Where charges are taken from capital, this may constrain future growth. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. If any currency differs from the investor’s home currency, returns may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Investment objectives and performance targets are subject to change and may not necessarily be achieved, losses may be made.

1 This stock is held in 4Factor portfolios.

2 Some of these stocks are held in 4Factor portfolios.

No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those achieved in the past, or that significant losses will be avoided.

This is not a buy, sell or hold recommendation for any particular security. For further information on specific portfolio names, please see the Important information section.

All investments carry the risk of capital loss.

Important Information

This communication is provided for general information only should not be construed as advice.

All the information in is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete. The views are those of the contributor at the time of publication and do not necessary reflect those of Ninety One.

Any opinions stated are honestly held but are not guaranteed and should not be relied upon.

All rights reserved. Issued by Ninety One.

Specific Portfolio Names

References to particular investments or strategies are for illustrative purposes only and should not be seen as a buy, sell or hold recommendation.

Unless stated otherwise, the specific companies listed or discussed are included as representative of the Fund. Such references are not a complete list and other positions, strategies, or vehicles may experience results which differ, perhaps materially, from those presented herein due to different investment objectives, guidelines or market conditions. The securities or investment products mentioned in this document may not have been registered in any jurisdiction. More information is available upon request.