Globalisation isn’t dead. It’s just being radically re-oriented, with Asia – the Orient – as its centre of gravity. That poses some crucial questions for investors.

Contents

01 Preamble

02 From where we stand: perspectives on globalisation

03 How globalisation got to where it is now

04 De-Americanisation and the wider context of globalisation

05 The changing world of globalisation: Asia’s gravitational pull

06 Going with the flow? Key questions for investors

07 Podcast: exploring China’s rise with strategist Michael Power

01 Preamble

A Google search for ‘Globalisation is dead’ highlights a revealing divide. Western journals and think-tanks often agree. Their equivalents elsewhere rarely do.

Even in most of the Western death notices, there is nuance. But many concur with Adam Tooze’s assessment in The Guardian that “the broader vision of the flat world of globalisation is dead”1.

The idea of globalisation’s demise long pre-dates Donald Trump’s trade schism with China in the run-up to the 2020 election, and his subsequent dubbing of COVID-19 “the China virus”. As The Economist put it, “Even before the pandemic, globalisation was in trouble”2. So too was the philosphy that defended it, globalism – though only in the West.

Back in 2016, in the wake of Trump’s election victory, journalist Paul Mason correctly sensed the tone of the coming four years, noting “Globalisation is dead, and white supremacy has triumphed”3. The two ideas are not often connected. But with the Trump experiment over, it can now be seen that the version of world order – economic order included – centred on the ‘white man’ and more broadly the West is drawing to a close.

“The version of world order centred on the ‘white man’ and more broadly the West is drawing to a close.”

Talk of the order’s passing escalated during the Trump presidency. By 2018, it had become central to the US political debate. In a speech in Houston, Trump said: “You know what a globalist is? A globalist is a person that wants the globe to do well, frankly, not caring about our country so much.” He went on to describe what he saw as the political philosophy that opposed globalism: “You know what I am? I’m a nationalist, okay? Nationalist. Nothing wrong. Use that word.”

But not everyone agrees that globalisation is an idea whose time has come and gone. Far from it. Beyond the West, many believe it is simply evolving – and fast – to a new structure in which Asia will be the centre of gravity. For investors, the implications are likely to be profound.

1 ‘The death of globalisation has been announced many times. But this is a perfect storm’, The Guardian, June 2020.

2 ‘Has covid-19 killed globalisation?’, The Economist, May 2020.

3 ‘Globalisation is dead, and white supremacy has triumphed’, The Guardian, November 2016.

02 From where we stand: perspectives on globalisation

Many in the West think globalisation is finished and being replaced by a fragmented world order. Elsewhere, they think it is merely re-orienting.

Academic articles chronicling globalisation’s journey over the past three decades are in a strikingly different vein to Francis Fukuyama’s ‘End of History and the Last Man’, published in 1992. Writing not long after the Berlin Wall had fallen, Fukuyama definitively declared that liberal democracy had beaten communism and from then on democratic capitalism would be the political order of choice.

In this triumphalist prognosis, there was a sense of permanence about the pattern that future political orders would likely take. Fukuyama has since heavily qualified his thesis. But back then, he was looking forward, describing what he saw as the start of a settled world following the end of communism. By contrast, ‘the death of globalisation’ discussion looks backward, seeking to understand the end of a known world and its succession by an era of unsettled, and unsettling, questions. Two are often posed: is liberal democracy the best political system?; and, is capitalism the most productive economic order?

These questions raise doubts over the staying power of the political and economic philosophies that Fukuyama thought would endure. It is perhaps ironic that one of the many proposed successors of globalisation – indeed, one of the solutions proffered for dealing with the fall-out of its supposed demise – is that which Fukuyama predicted was dead and gone: socialism. The fact that less-than-democratic, only-partially-capitalist China is the big winner of the past two decades flatly contradicts Fukuyama’s forecast.

Fragmented we stand?

Those writing globalisation’s obituary have always felt something else would come next. Michael O’Sullivan, discussing his book ‘The Levelling’ in The Economist1, posits that a new, less integrated order will replace globalisation. His forecast is increasingly shared in the West: the emergence of a more fragmented world rotating around multiple axes. Macro strategist Nader Mousavizadeh calls this fragmented world of globalised enclaves an “archipelago” that will henceforth be far more complex and difficult to navigate.

As an aside, one can argue that, until the late 1980s, the world was already divided into blocs, both politically and economically. While the Western archipelago might have been dominant, it was not universal. And not every part of the world was drawn into a single bloc even after the fall of the Soviet system. Much of Africa and parts of Latin America, the Middle East, and South and Central Asia continued to follow their own paths.

But three events in rapid succession transformed the global economic map: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Rao’s Indian liberalisation programme in 1991 and Deng Xiao Ping’s Southern Tour in 1992. They led to an acceleration in the trade connectivity between the various spheres of economic interest, re-involving Russia and the Eastern Bloc, India and China more closely in global trade flows. However, increased capital connectivity was only to happen at a far slower pace and, in China’s case, only under very controlled circumstances.

Not dead, but moving on

Exactly what order might now succeed the form of globalisation as heretofore defined in the West, that which evolved after 1989, is perhaps best glimpsed by looking beyond the rising trade barriers of much of the West, where even the EU now preaches ‘strategic autonomy’.

In other parts of the world, the prevailing sense is that globalisation is not dead but moving on from the ‘white-man’ vision of globalisation. Even some Western nations – notably a post-Brexit Great Britain, or ‘Global Britain’ as Boris Johnson calls it – appear to acknowledge this: hence the UK’s reqest to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Rafik Nayed, writing an opinion in Arabian Business suggests, “Globalisation is evolving, not dying – just look to the Middle East”2. Or as the title of an article by Parag Khanna sums it up in Nikkei Asia, ‘The next wave of globalisation: Asia in the cockpit’3. Nikkei Asia’s Editorial Board titled its cover story of 18 January 2021 ‘The Age of Re-Globalisation’.

“Our thesis is that globalisation is being re-oriented into a global trading pattern in which the West, and especially the US, is no longer in the cockpit. Asia is.”

This evolving globalisation will likely alter its form, its function and, most importantly, its geographic centre of gravity. Our thesis is that globalisation is being reconfigured; or – in both meanings of the word – re-oriented. It is being transformed into an updated global trading pattern in which the West, and especially the US, is no longer in the cockpit. Asia is. The big question facing global investors is, with commercial trade patterns recentering on Asia, what will be the knock-on effects on capital flows which, for the time being, are still very much centred on the West.

To answer it, it helps to understand how globalisation has evolved to date, and why attitudes towards it are now so different in different parts of the world.

1 ‘Globalisation is dead and we need to invent a new world order’, The Economist, June 2019

2 ‘Opinion: globalisation is evolving, not dying – just look to the Middle East’, Arabian Business, May 2020.

3 ‘The next wave of globalization: Asia in the cockpit’, Nikkei Asia, January 2021.

03 How globalisation got to where it is now

Globalisation has had a high cost for some. But many still see advantages in a globalised trading system.

There are many facets to globalisation, so much so that the term has come to mean very different things to different people. And, as noted above, its meaning is evolving. But while globalisation had its early critics, until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 its most common definitions had an almost mechanical character, describing its traits without passing judgement. The characteristics cited most frequently were:

- It involved the spread of all aspects of commerce across nations almost everywhere.

- While the trade in goods unsurprisingly received the most attention, it also included trade in technology and information services, as well as the location of employment opportunities, sometimes even triggering cross-border movement of labour.

- The main practitioners of globalisation were the multinational corporations, especially (but not only) those located in the West.

- It frequently resulted in complex global supply chains, involving outsourcing of production to contract manufacturers – finished-product suppliers located in lower-labour-cost countries than the end-consuming country.

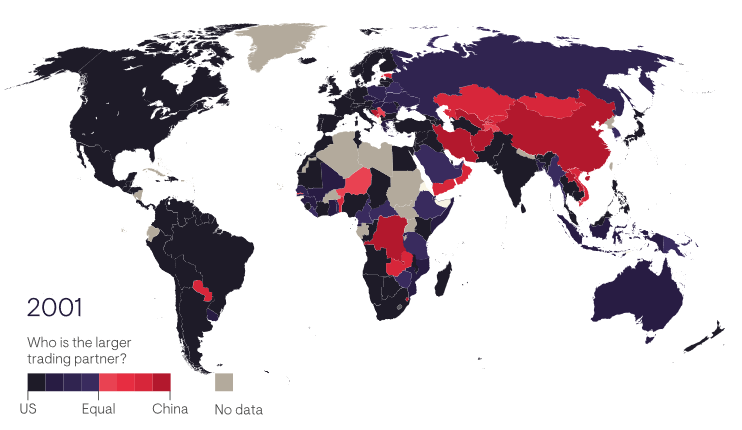

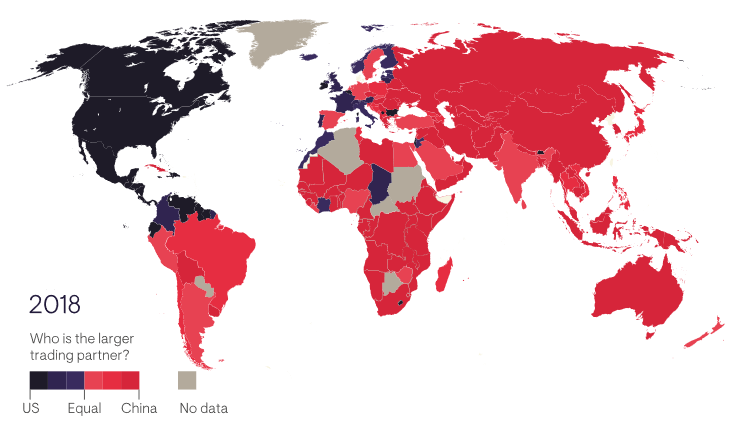

As longer-term global trade patterns shifted decisively following China’s 2001 joining of the WTO (see maps below), and visibly accelerated in the decade after the GFC, globalisation morphed into a much bigger phenomenon as its second-level implications – social, cultural, legal and especially political ones – came to be more fully and widely understood.

Digitalisation quickened globalisation’s spread, as well as increasing its reach into the remotest of places. Automation and even artifical intelligence entered the equation, further muddying the waters of intra-country labour costs. (China is by far the world’s largest buyer of industrial robots.)

A more balanced appraisal

Initially, the media focused on the gains from globalisation – employment opportunities for Asian workers who, in turn, made cheaper goods for Western consumers being the ‘win-win’ that was widely noticed. But before long the losses were registered too, in particular the steep decline in blue-collar, manufacturing jobs in the West. And where jobs were not lost, a cap on wage growth often resulted. The ‘China price’ turned from being a blessing of cheap goods to a curse of low wages for many Western workers. There was much more to globalisation than this summary but, as reflected in Western political rhetoric, this was the essence of it.

This growing antipathy towards globalisation in the West was far from universal. The negative fall-out for Main Street was obvious even as Wall Street stayed focused on globalisation’s commercial advantages. Since multinationals did well from globalisation – through rigorously constructed, cost-effective supply chains, often reinforced by a parallel process of minimising tax bills through transfer pricing and other profit-shifting behaviour involving low-tax nations, such as Apple’s use of Ireland – many investors doggedly defended it: it increased pre-tax and post-tax profits of the companies that practiced it and their share prices rose as a result. This was the world of Davos Man, a term coined by Samuel Huntingdon. Davos Man, he wrote, had “little need for national loyalty, viewed national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully were vanishing, and saw national governments as residues from the past whose only useful function was to facilitate the elite’s global operations”1.

That this further exacerbated both income and wealth inequality, especially in consuming countries, was countered by getting-richer investors who claimed it was a price worth paying. Donald Trump was later to eulogise a soaring Dow Jones, even though its rise was in large part supported by a trend he strongly opposed: globalisation. In doing so, he was ironically finding common cause with the globalist Davos Man.

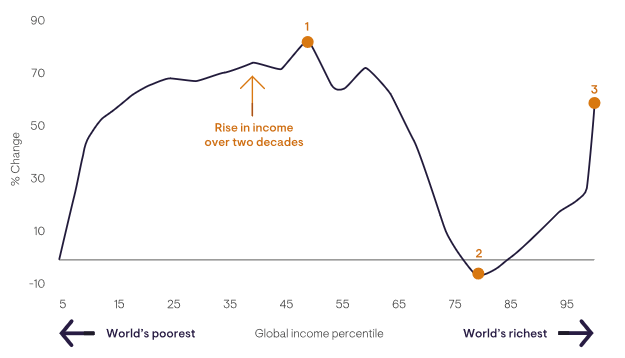

Branko Milanovic’s now famous ‘elephant’ chart summarised this process. Industrial workers in the emerging world (mostly Asia) did well in terms of rising incomes from 1988-2008 ( point 1 on the chart) even as their equivalents in the developed world did not (2). The very rich – epitomised by ‘Wall Street’ – prospered regardless (3).

Figure 1: Change in real income between 1998 and 2008

Source: Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, BBC. Please note that this chart has been redrawn by Ninety One.

Unsurprisingly, even before Donald Trump moved to the centre stage of politics, everyday Western usage of the ‘globalisation’ word had started to be imbued with negative connotations. Today, many middle-class Westerners, especially those who have been economically ‘left behind’ as a result of its implementation, regard globalisation as a swear word born of twenty-first century business practices. The mob that invaded the Capitol on 6 January 2021 specifically noted that they were there to rid the US political structure of its globalists. And as writer William Pesek noted of the recent flash mob of little-guy retail investors upending Wall Street, a “Reddit uprising” was beating “Davos Man at his own game”2.

A more sanguine perspective

For its part, the non-Western world is generally more sanguine about the idea of globalisation. It has brought ample employment opportunities in these countries, even if those employed could not initially afford their own output. As Chinese workers quipped 20 years ago, “We make TVs; Americans watch them”. Today, no consumers buy more TVs than the Chinese.

“On balance, Asia views globalisation positively. But this is hardly surprising, since Asia has been its principal geographic beneficiary.”

On balance, Asia views globalisation positively. But this is hardly surprising, since Asia has been its principal geographic beneficiary. Like the cause of ‘free trade’ – and the two are interconnected, for globalisation has been likened to the specialisation doctrine at the heart of free trade taken to its logical conclusions – supporting globalisation has become the mantra of the countries that benefit from it most.

As President Xi Jinping recently said at the Singapore Davos 2021 – that the location of Davos was shifted to Singapore is in itself revealing – China will continue to promote economic globalisation and advance technology and innovation. China, he said, is further committed to following through on its policy of opening up and will continue to promote trade and investment liberalisation. There are none so zealous as the converted. Apart from the winners.

1 ‘Dead Souls: The Denationalization of the American Elite’, Samuel Huntington, The National Interest, March 2004.

2 ‘Reddit uprising beats Davos Man at his own game’, Nikkei Asia, 1 February 2021.

04 De-Americanisation and the wider context of globalisation

Globalisation America-style may be dying; but a less US-centric version could take its place.

The process by which Western, and especially American, multinationals were to benefit from globalisation was grafted onto a world where the US stood tall across many spheres. Even prior to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, militarily the world was uni-polar and the US was its hegemon. After 1991, without even a Russian pretender to America’s throne, there was no doubt about it: the US ruled the roost.

The US had by far the largest economy. Its capital markets were the weightiest, its companies were the most valuable and world trade was dominated by dollar-invoicing. The yield on the 10-year US Treasury bill determined the global cost of mobile capital. No country matched the US’s technological prowess, and its R&D spend eclipsed everyone else’s. The US had the world’s best universities. And the world’s richest (mostly) men were mostly American. With these advantages, it was natural for US multinationals to define the rule-set that was to govern globalisation in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century.

“Globalisation America-style may indeed be dying; but this does not mean a less US-centric version of globalisation will not take its place.”

But now, in the 2020s, part of the contention that ‘globalisation is dying’ arises because its path forward is no longer overwhelmingly defined by American preferences and reinforced by American national strengths. Globalisation America-style may indeed be dying; but this does not mean a less US-centric version of globalisation will not take its place.

US-centric globalisation typically focused on the supply side, indeed overly so – in particular, how China had become the ‘factory of the world’ and everyone else increasingly dependent on ‘Made in China’. (When the COVID pandemic erupted, the US woke up to realise that roughly 90% of its PPP supplies and even antibiotics came from China.) But a parallel feature that helped define the patterns of globalisation, which has gone underappreciated, has been the distribution of absolute levels of consumption. Not only does the US still have an economy that is some 50% larger than second-placed China, over 70% of US GDP is accounted for by consumption. Even today, American consumption alone is still larger than China’s total GDP. Chinese production would not have prospered so had it not been met by Western – and especially American – consumption.

China’s rise

This is changing very fast. China’s nominal US dollar GDP is growing far faster than the US’s, increasing by over 10% in 2020 alone, with over 70% of that rise being in currency effects. Naturally, the size and value of China’s consumption pool is growing too. And even within China’s GDP, consumption as a share of total GDP is rising.

Why is this important? For the 2000-2020 period, the core (but of course not only) flow of trade globalisation has been the sourcing and importing of products by American companies in and from Asia, often from contract manufacturers; these goods were then sold to American consumers. Before COVID, Walmart alone was responsible for 5% of trans-Pacific trade, nearly all of it from Asia to America. Chinese exports to the world beyond America piggy-backed upon this core flow.

In the coming decade, the geographic patterns of consumption – and especially its growth – will change fundamentally. According to research group Brookings, during the 2020s, 90% of the billion people expected to join the middle-classes will do so in Asia. Western multinationals will no doubt cater to a share of this growth. But Asian multinationals, and not only Chinese players, will service most of it. This one detail more than any other will help define the character of globalisation going forward: it will be constructed upon the foundation no longer of American but of Asian demand. That it will still also be serviced in large part by Asian production makes this supply and demand yin and yang especially powerful. The additional fact that this growth will occur largely without incurring significant debt, at either the national or the personal level, will make it doubly so.

05 The changing world of globalisation: Asia’s gravitational pull

China’s rise means that, by 2030, the geometry of trade globalisation will be vastly different from today.

How much China has changed the global trade map is best illustrated in the ‘before’ and ‘after’ maps below. The start date is 2001, when China entered the WTO. The world was largely blue, with the US dominating bilateral trade patterns. By 2018 it was mostly red, as China had supplanted the US.

Figure 1: How China changed the global trade map

Source: Lowy Institute calculations, IMF Direction of Trade Statistics database. Please note that this figure has been redrawn by Ninety One.

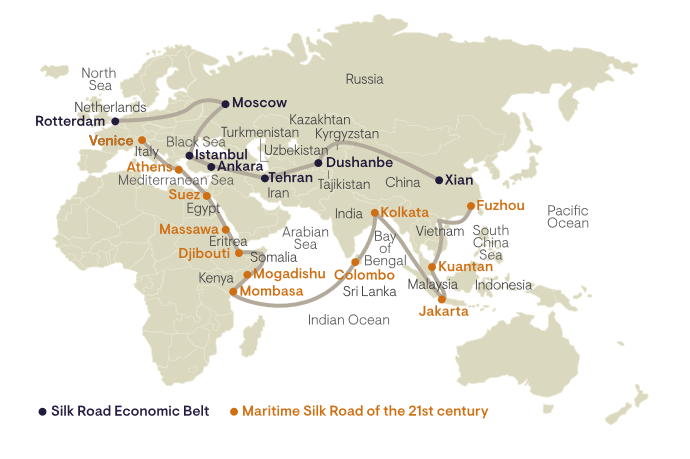

No map reinforces this transformation more than that of the ‘One Belt, One Road’ – or BRI, for ‘Belt & Road Initiative’ – geo-economic vision now being implemented by Beijing.

Figure 2: Trade routes for the Belt and Road initiative

Source: www.mapsofworld.com. Please note that this figure has been redrawn by Ninety One.

Now add in the following forecasts:

- By 2030, China’s economy will have likely eclipsed that of the US in size.

- By 2030, the world’s largest free-trade zone, the newly formed RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), which is centred on the East Asian time zone, will see its share of global GDP rise from 30% in 2020 to 50% by 2030.

- As noted before, in the coming decade, Brookings predicts that of the 1 billion people joining the middle class worldwide, 90%+ will be in Asia. In the US and Europe, middle class numbers may actually decline outright.

“The bottom line is that by 2030 the geometry of trade globalisation will be vastly different from that with which the West is familiar.”

The bottom line is that by 2030 the geometry of trade globalisation will be vastly different from that with which the West is familiar.

- Goods supply chains globally will increasingly not just lead from Asia but into Asia as well, as already happens with natural resources.

- Asia will be the world’s principal finished-goods producer.

- The critical change will be that Asia’s principal customer will be itself.

06 Going with the flow? Key questions for investors

As well as re-orienting regionally, globalisation will increasingly be defined by capital flows as well as trade.

There are two big questions for investors:

- What will the evolution of globalisation mean for the pattern of capital flows globally in the coming decade?

- Will the pattern which emerges undermine or refashion the Americanisation of global capital which the world has known since 1945?

The globalisation of capital by 2030 will likely see a much larger share of border-crossing capital destined for Asia, be it to fixed income or equity instruments. And, with Asia’s middle classes ballooning, that flow from outside Asia will likely be supplemented by flows from within a savings-rich Asia being applied to an investment-opportunity-rich Asia. Already Hong Kong’s share transactions outnumber London’s four-to-one.

Central to the destination of these flows, be they international or regional, will be China and its trio of interconnected capital markets, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen. India will be the second-largest destination. Singapore will likely cement its claim as the capital of private wealth in the region, the Switzerland of Asia.

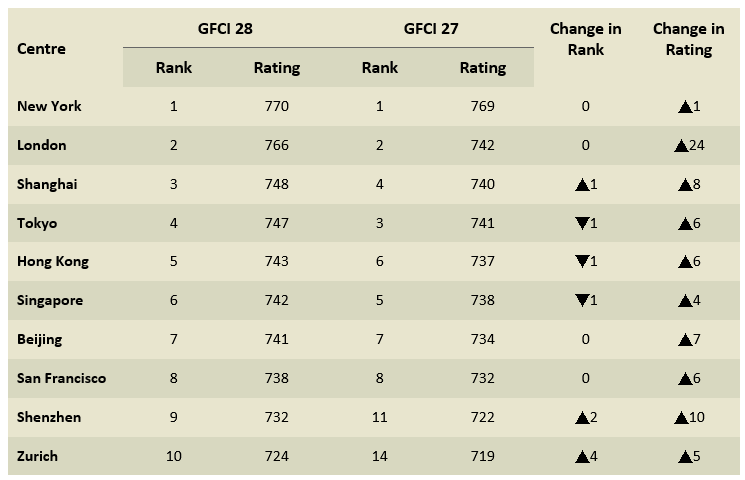

Just how influential Asian – and especially Chinese – capital markets have already become is writ large in the 2020 Global Financial Centre Index. In the top 10, China has four entries, the US has two and no other nation has more than one. Regionally, East Asia has six, the Americas two and Europe two, neither of which are inside the EU.

Figure 1: Asia ranks as largest region in the Global Financial Centre Index in 2020

Source: Longfinance.net, 2021.

By 2030, China’s capital markets – though by no means a carbon-copy of what is defined as ‘best practice’ in the West today – will be a known quantity: more transparent, better regulated and less bureaucratic than in 2021. Foreigners will ask far fewer of the “But can I trust Chinese markets?” type of questions by 2030. Of India, likewise. Though as yet to topple the primacy of the US dollar in the world of capital, the renminbi and the rupee will also by then be well-known quantities.

One skill that investors already practice today but which will be of paramount importance by 2030, will be currency management. In parallel, investors will also pay a lot more attention to comparative country risk assessment than they do even today.

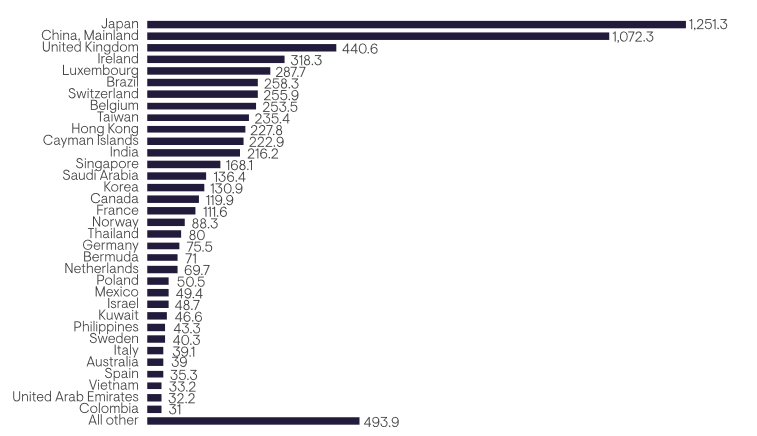

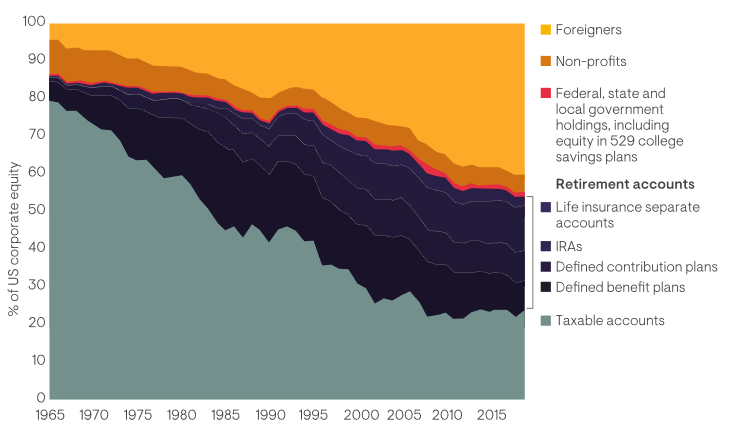

Since 1989, globalisation has been mostly about the globalisation of trade, and only to a lesser degree the globalisation of capital. The big exception to this has been the continued willingness of the non-US world to fund US current-account deficits with capital flows. The result is very evident in US bond and equity markets (as highlighted in figure 2). The US equity market is now some 40% foreign owned (see figure 3 below).

Figure 2: Foreign holdings of US Treasuries as at September 2020

.

Figure 3: Ownership of US corporate stock, 1965-2019

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Financial Accounts of the United States;” Tax Policy Center calculations. Please note that this chart has been redrawn by Ninety One.

07 Podcast: exploring China’s rise with strategist Michael Power

China’s rise is re-orienting the patterns of international trade, posing some challenging questions for investors long used to a Western-dominated global economy. Investment strategist Michael Power argues that, to understand how the world is changing, it’s essential to learn to look at the world through Chinese eyes. In these conversations, he explores how China is uprooting the status quo, and what that means for portfolios.

Michael Power. Re-Orientation Podcast Part 1

Duration: 9m36s

Michael Power. Re-Orientation Podcast Part 2

Duration: 9m45s

Disclosures and important information

General risks. The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise. Where charges are taken from capital, this may constrain future growth. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. If any currency differs from the investor’s home currency, returns may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Investment objectives and performance targets are subject to change and may not necessarily be achieved, losses may be made.

Specific risks

Currency exchange: Changes in the relative values of different currencies may adversely affect the value of investments and any related income. Emerging market (inc. China): These markets carry a higher risk of financial loss than more developed markets as they may have less developed legal, political, economic or other systems.

General Risks

All investments carry the risk of capital loss. The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise and will be affected by changes in interest rates, currency fluctuations, general market conditions and other political, social and economic developments, as well as by specific matters relating to the assets in which the investment strategy invests. If any currency differs from the investor’s home currency, returns may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those achieved in the past, or that significant losses will be avoided.

This is not a buy, sell or hold recommendation for any particular security. For further information on specific portfolio names, please see the Important information section.

———————————————————————————————————————–

All investments carry the risk of capital loss.

Important Information

This communication is provided for general information only should not be construed as advice.

All the information in is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete. The views are those of the contributor at the time of publication and do not necessary reflect those of Ninety One.

Any opinions stated are honestly held but are not guaranteed and should not be relied upon.

All rights reserved. Issued by Ninety One.