This is the third part in a series of six columns from WTW’s Thinking Ahead Institute exploring a new risk management framework for investment professionals, or what it calls ‘risk 2.0’. See other parts of the series here.

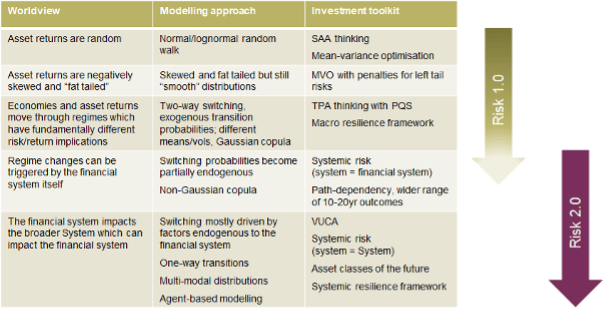

In this piece we explore the spectrum of “world views” that could be embedded in an investor’s risk mindset and the associated risk practice that would be consistent with each of them, with the aim of identifying where the “jump” from risk 1.0 to risk 2.0 occurs.

Asset returns are random (risk 1.0)

The simplest worldview that is of some practical use would be that the returns on all asset classes are a random walk (ie independent through time) and drawn from normal or lognormal distributions that are correlated with each other in a given time period.

This formulation is aligned with the mindset of Markowitz (1952) from which risk practices including mean-variance optimisation and Capital Asset Pricing Model emerged.

Asset returns are negatively skewed and “fat-tailed” (risk 1.1)

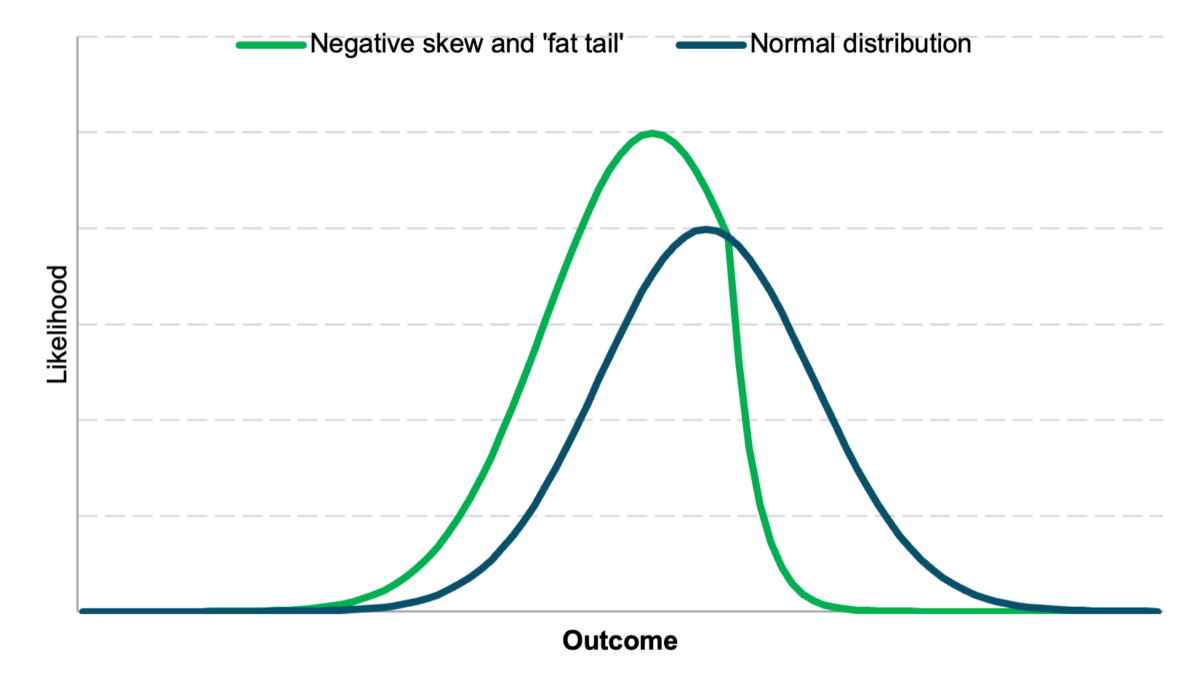

Most undergraduate finance courses teach that asset returns are typically negatively skewed and “fat-tailed”. This means:

- adverse outcomes are more extreme than positive outcomes; and

- extreme market movements are more likely than is predicted by a normal distribution.

- negative skew is a natural feature of certain asset classes (eg corporate bonds, insurance-linked securities) and trading strategies (eg carry strategies, short volatility)

- market responses to bad news (fear) tend to be more significant than to positive news, ie “the market goes up by the escalator but down by the elevator shaft”.

The corresponding risk practice could include:

- adopting non-normal (but still smooth/continuous) distributions to represent asset return outcomes to better reflect likely downside risk outcomes (eg CVaR)

- greater focus on risks that actually matter (ie mission impairment) and less focus on short-term volatility

- incorporating higher moments into optimisation processes, eg defining a utility function that factors skew and kurtosis into portfolio evaluation.

Economies and markets exhibit different regimes (risk 1.x?)

A further evolution of the risk mindset would be to recognise that economies and asset markets move through regimes which have materially different risk and return implications. This could, for example, be expressed via a “good” environment (high return, low volatility, diversification works) and a “bad” environment (negative return, high volatility, diversification fails).

Additional enhancements to risk practice that would be consistent with this include:

- allowing for characteristics of asset returns to be time-varying rather than stationary

- allowing for economies and markets to “switch” between two or more regimes with pre-determined probabilities

- creating dependencies between asset classes that reflect real-world economic relationships in these regimes (eg property returns should reflect changes in bond yields as the latter are an input to valuation processes)

- assuming asset returns are autocorrelated/mean reverting (vs assuming independence through time).

Beyond modelling aspects, other areas of risk practice that have evolved over time include:

- development of forward-looking scenarios to define regimes and stress test portfolios

- use of risk factors or return drivers to understand portfolio diversity and likely robustness to different economic regimes

- use of multiple lenses/dashboards and qualitative considerations to inform investment decisions with less reliance on quantitative optimisation.

Regime changes triggered by the financial system (risk 1.9x/risk 2.0?)

What has been described up to this point represents best-in-class current risk practice which embeds an important underlying assumption – that “shocks” to economies and markets are exogenous (externally driven). However, as was observed in the Global Financial Crisis, shocks causing system-wide effects can originate from within the financial system (ie shocks can be endogenous as well as exogenous).

A first important step towards a risk 2.0 mindset is therefore to recognise that regime changes can be triggered by the financial system itself due to the behaviour of agents within the system. In addition, these regime changes are usually “accumulating in the background”. This adds a belief that economies and markets are complex adaptive systems, which should lead to more significant changes in risk practice than described previously. In particular:

- switching probabilities are partially uncertain at the outset and respond to the prevailing regime

- more sophisticated representations of interconnectedness within the financial system than correlation matrices

- incorporation of path dependency – if regime changes are accumulating in the background this means that Markovian models that only “look at” the current state of the system are insufficient

- widening the distribution of 10/20 year outcomes beyond conventional models that assume risk on an annualised basis reduces with the square root of time.

The financial system is part of a broader System (risk 2.0)

An important limitation of the risk mindset described above is the focus on the financial system in isolation. In reality, the financial system is a part of the broader (capital-S) System which has “nested” boundaries around society, the human environment and then the planet itself. Importantly, actions of agents in the financial system can impact the broader System (eg climate change, inequality) which in turn can have impacts on the financial system (this is commonly referred to as “double materiality”).

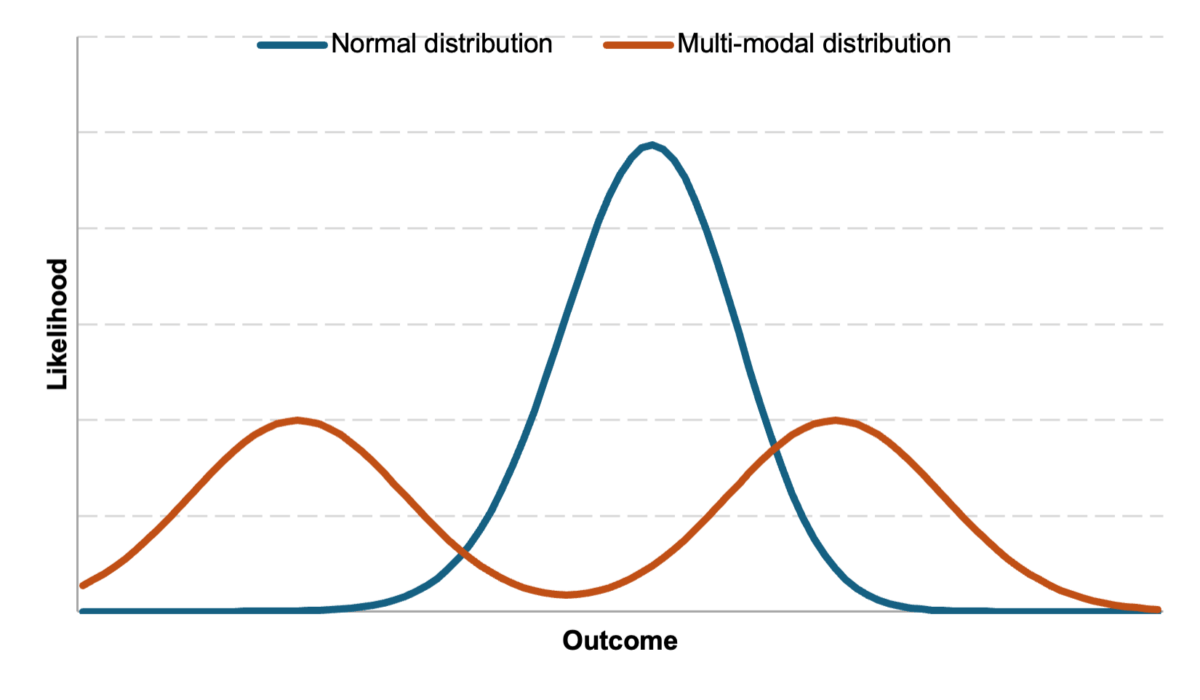

A second related evolution is incorporating “tipping points” which once crossed are very difficult, or impossible, to reverse, ie these can result in permanent transitions of economies, society and environment. Crossing tipping points can trigger systemic risks which result in permanent impairment or stranding of certain sectors of the economy. This is very different to a large fall in markets due to (for example) an economic shock, as these losses are permanent and not subsequently made up.

This suggests that further significant shifts in risk practice are required including:

- greater use of qualitative risk measures as there is a natural limit to the usefulness of quantitative models in the measurement and management of systemic risks which are highly non-linear and largely irreducible.

- the use of multi-modal or discontinuous distributions, as the outputs from different systemic risk scenarios are likely to be very differentiated in terms of economic, social and environmental (and therefore financial asset return) outcomes.

- incorporation of “one way” transitions and absorbing states into risk models to represent tipping points can cause mission impairment – this increases the importance of thinking about risk in time series rather than cross-section due to the “irreversibility of time”.

- shifting focus from portfolio-level risk management to system-level risk mitigation, as it is highly unlikely that:

- the impact of systemic risk on portfolios can be reduced through asset allocation as systemic risks are pervasive; and/or

- that a portfolio can be constructed that is robust to a range of systemic risk scenarios as systemic risks are generally highly non-linear

- development of dashboards to monitor the accumulation of systemic risks to allow strategic adaptation of the portfolio as the probability of different scenarios and crossing of tipping points changes over time.

The table below summarises the journey from risk 1.0 to risk 2.0 in terms of changes in world view and the resulting investment toolkit. We conclude that the shift from risk 1.0 (or risk 1.x) to risk 2.0 is both transformational (rather than incremental) and can only be partially achieved by the use of quantitative models.

Jeff Chee is global head of portfolio strategy at WTW.