Dutch pension giant APG Asset Management has built a three-pronged framework for public infrastructure investments, linking each prong to the government’s level of control and guiding its own ownership and cash flow decisions.

It has become increasingly relevant as global asset owners face pressure to invest domestically, with politicians turning to private capital to fund national priorities amid growing budget deficits.

In the UK, the 17 largest workplace pension providers have pledged to invest at least 10 per cent of their defined contribution assets in private markets (half of that is earmarked for the UK) by 2030, under the Mansion House accord which is touted to release up to £50 billion in capital.

Real assets in particular are under the spotlight due to their connection with key economic and social issues including housing, energy and digitisation. Their importance is exemplified by the Future Fund’s move to partially internalise its direct infrastructure and property investments in Australia this June, opening doors to defence-related investments and other areas of national priorities where there is a lack of manager coverage.

A report by the International Centre for Pension Management (ICPM) found infrastructure investors share a common gripe when dealing with the public sector: they argue governments often struggle to articulate the desired outcomes, investment timelines or exit strategies, which could lead to poorly structured projects or unrealistic expectations.

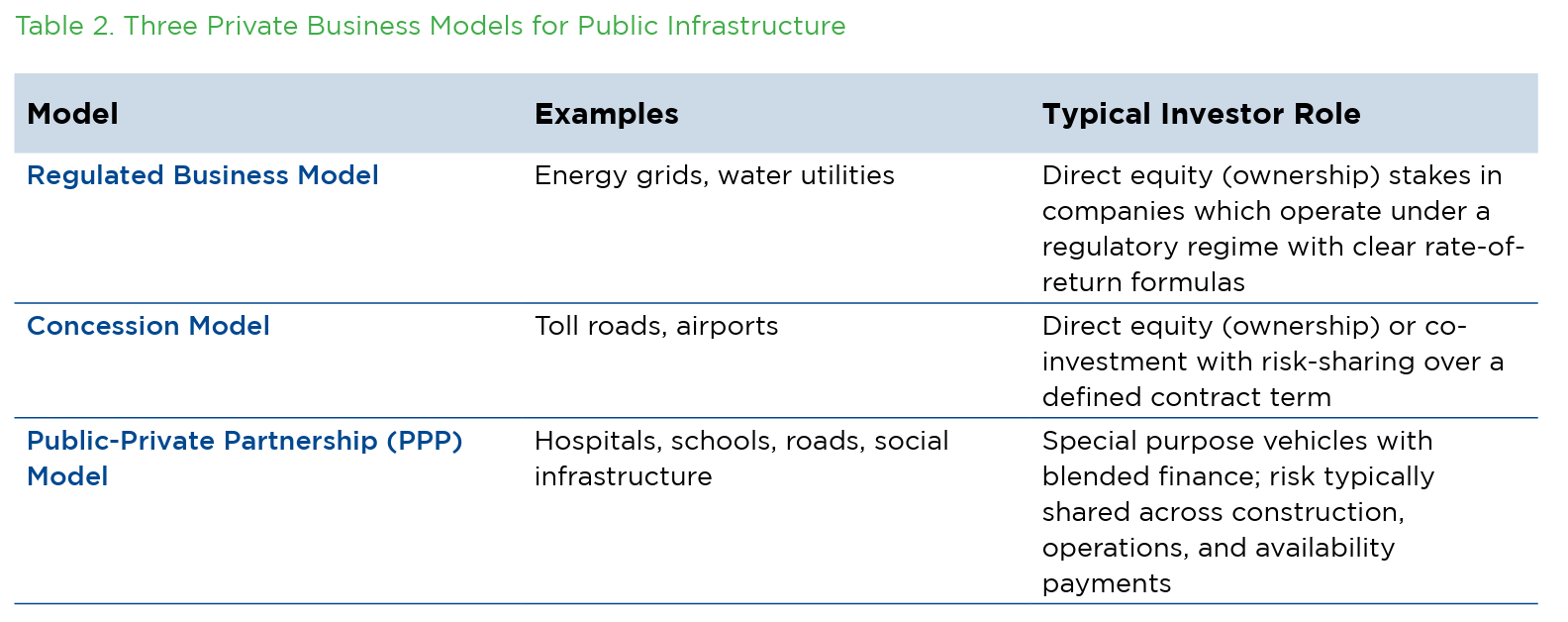

APG is addressing this ambiguity by segmenting its public infrastructure investments into three models – regulated business, concession and public-private partnership (PPP) – which have different degrees of involvement from the government.

For example, investors can own the assets indefinitely in the regulatory business model but only for a pre-defined period in the concession model. The government retains asset ownership in the PPP model while allowing private investors to develop or operate the asset, leading to a higher degree of control.

In terms of cash flow, while private investors make an upfront payment to the government and try to recoup the cost via ongoing revenue in the regulated business model (such as consumer energy bills), they receive a fixed remuneration over time from the government under PPP for developing and operating the asset.

One asset owner surveyed by the ICPM report noted the discrepancy between short political cycles and long-term investment horizons as a key challenge.

Aligning the expectations between public and private sectors early would help make sure the project falls inside the “investible window” – defined as a set of sound legal, financial, and governance conditions that must simultaneously exist for an investment to fulfil the fiduciary duty, the report said.

Having institutional investors assess investments in a robust way will only benefit governments and attract investors.

Ultimately, the key to incentivising domestic investments is a structural one, and only if governments acknowledge the institutional constraints that asset owners work with can they design projects that would attract capital, the report said.

“Patriotic appeals and mandates are not the solution. Institutional capital is not deterred by a lack of interest but by a lack of fit,” the ICPM report said.

Staying vigilant

The report also outlined that even when contractual frameworks and governance mechanisms appear sound, success is never guaranteed with the shadow of troubled projects like the UK’s Thames Water still looming large.

On paper, Thames Water counts typical infrastructure traits including stable and predictable cash flows that are attractive to investors, but its practice of using an over-leveraged balance sheet to pay dividends pushed the company to the edge of insolvency. Canada’s OMERS wrote off its entire 31.7 per cent stake, which was valued at £990 million ($1.32 billion) at the end of 2021, among other investors who took significant losses including BCI and PGGM.

The ICPM report emphasised the importance of having a sound governance structure when managing operationally complex infrastructure projects, which means establishing a special purpose entity (SPE). It protects investor rights by overseeing significant corporate actions such as material asset dispositions, ensuring clear exit pathways and mitigating equity dilution risks.

Investors should also rigorously self-assess their alignment with different domestic investment projects, starting with aligning their fund types with project briefs, the report said.

For example, large corporate pension funds tend to be more compatible with risk-averse projects due to liability needs and should look for briefs with clear return prospects and liquidity, while avoiding “early-stage or politically sensitive investments”.

Large public pension and sovereign wealth funds can be early investors in commercially viable projects provided they have strong governance, while development and infrastructure banks have a crucial role in de-risking projects and providing institutional guarantees.