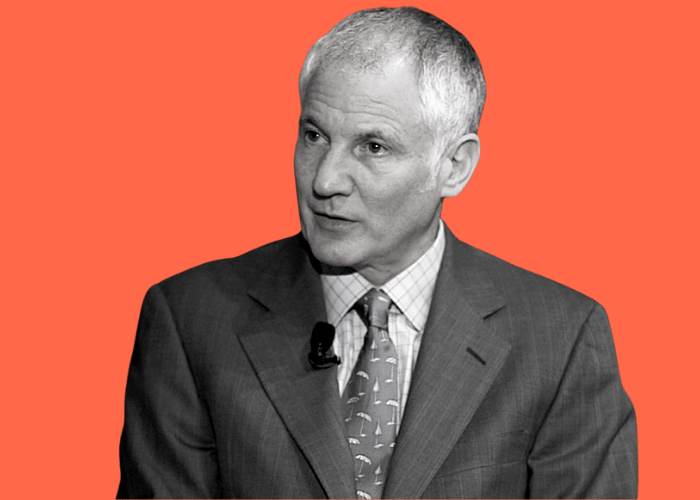

Perhaps the biggest threat to Chinese growth is the lack of education and skills of its people, said Stephen Kotkin, Professor in History and International Affairs at Princeton University speaking at FIS Digital 2021. In a presentation on investor risk and opportunity in China he argued that unless China can improve its education system, the country will remain in the middle-income trap. Kotkin questioned whether investors might seek growth in Asia outside of China.

Globalisation has helped low- and high-income countries, but surprisingly few middle-income countries have been able to climb into the higher bracket.

Countries like Spain, Portugal and Greece climbed higher with the support of the EU, others like Australia and Japan have done so via investing in their human capital. China, unlike neighbours in Taiwan or Singapore, has not invested in its people to the same extent with an estimated 70 per cent of the population uneducated and only 30 per cent passing through high school. Kotkin compared China’s challenges to Mexico which “hit a wall” because of a lack of investment in human capital, ending its growth story and triggering an investor exodus.

Kotkin said that China has grown fast without investing in its people and the government understands the challenge and risk afoot. It is now playing catch up with initiatives like introducing vocational schools in rural areas. Yet he said these initiatives have also struggled. These schools became a box ticking exercise rather than a solution to the shortfall in education, he said. China needs to invest in its human capital in other areas too. For example, poor diet and health in rural areas are a blight on productivity, he said.

In contrast, Kotkin said other challenges often linked to a potential brake on Chinese growth are now less likely. For example, China’s absence of secure property rights or the lack of freedom and transparency is now less likely to halt progress. Arguments that China’s SOEs are crimping productivity, or the economy will stall on weak investment in the private sector and over capacity have worn thin by new trends like state firms seeking private sector partnerships to make them more efficient, and private firms participating in industrial policy.

He also urged FIS 2021 delegates to not to be naïve, and understand that the Chinese regime would accept slower growth for more control.

ESG

Kotkin said that China will have capacity to navigate some aspects of climate risk via its strength in engineering and infrastructure, noting how China is now buying nuclear capacity from Russia. If infrastructure and engineering solutions manage to counter climate risk, China may not hit a wall he said. Moreover, China can navigate its demographic challenge by encouraging older people back into the workforce in the same way Japan has done. Under the communist regime, the retirement age is low; a substantial population in China are able bodied and retired, he said.

Kotkin said that investors will increasingly struggle to integrate ESG in China. China fails on governance standards in most ESG calculations, he said. That said, he counselled on the importance of not painting China with a single brush, noting that many Chinese companies score well on governance but the government scores badly.

He urged investors to explore the difference and said running away from China because of genocide will not only punish retirees back home with lower returns by not investing in companies that are doing the right thing – it will also punish Chinese workers and populations. Against the backdrop of ESG reticence, he also noted a scramble and ambition among Wall Street firms (Amundi, Goldmans and JP Morgan amongst others) to capture the Chinese savings market.

In a discussion that included a range of questions from investors, Jay Willoughby, chief investment officer at TIFF asked for insight into decoupling trends between the US and Chinese economies. Kotkin responded that some supply chains are already moving out of China, although this is also linked to trends around wages and supply chain diversification. By relocating supply chains in countries like Vietnam firms can still benefit from Chinese growth, he said.

At US pension fund CalSTRS, China strategy is a board level issue and governance a particular concern. The pension fund is also navigating federal legislation regarding pension fund investment in China. Geraldine Jimenez, director of investment strategy and risk at the pension fund noted how China’s shortfall in skilled workers and human capital challenges meant the country didn’t have enough qualified workers for a knowledge economy. One consequence could be the emergence of value-add economies in cities and coastal areas but struggling interior economies; she also noted that the change of stance on the one child policy has eased the demographic challenges.

Tony Broccardo, chief investment officer at the United Kingdom’s Barclays Bank Pension Fund has focused his China strategy on private, venture investment. Describing a very positive experience, he explained how the fund has invested in China alongside many US venture capital firms. Now, as China’s markets begin to open up, he said questions remain around market access for capital providers. Moreover, investment comes against the backdrop of a hardening of narrative between the US and China and the risk of western policy makers becoming a barrier to investment. Broccardo noted how investors are already having to make a choice and pick sides against the backdrop of growing tensions.

Fellow panellist Olivier Rousseau, executive director at France’s FRR, argued that China made strategic mistakes by not taking earlier action to reverse demographic challenges. He also questioned why China continues to pour money into infrastructure and not invest in education. Kotkin responded that part of the problem has come from the pace of Chinese growth.

He said it is easier to throw money into construction than build an education system. He concluded that in China’s cities the universities are impressive but got outside the cities, and education lacks all nourishment.