Transparency is discussed so much that the word almost seems to suffer semantic satiation in policy and politics, but transparency is not for transparency’s sake.

Public pensions and other private capital investors know that the real goal of transparency is measurement for the sake of good governance, benchmarking, forecasting, and more.

A few pensions have demonstrated extraordinary results as a result of equal effort, no doubt. However, improved data standards for incoming reporting and a benchmark for pension disclosure is the two-part solution that will usher in constructive transparency.

Until then, pensions must contend with significant variation with incoming reporting and differences in statutory reporting requirements for their disclosures – differences that potentially create additional burdens on pensions. A two-part solution that is like two sides of the same coin is needed to bring comparability and consistency to the incoming and outgoing reports. Fortunately, there are a few pioneering efforts to accomplish just that.

Incoming data

As a former pension fund employee, the struggle for consistent and comparable data is something I came to understand well. The operations and reporting teams at countless asset allocators, pensions included, spend significant time and resources to collect and “scrub” investment data.

The level of time and resources required to make incoming data consistent and comparative is not equivalent to the expected task difficulty, but the devil is in the details – or more specifically, the lack thereof.

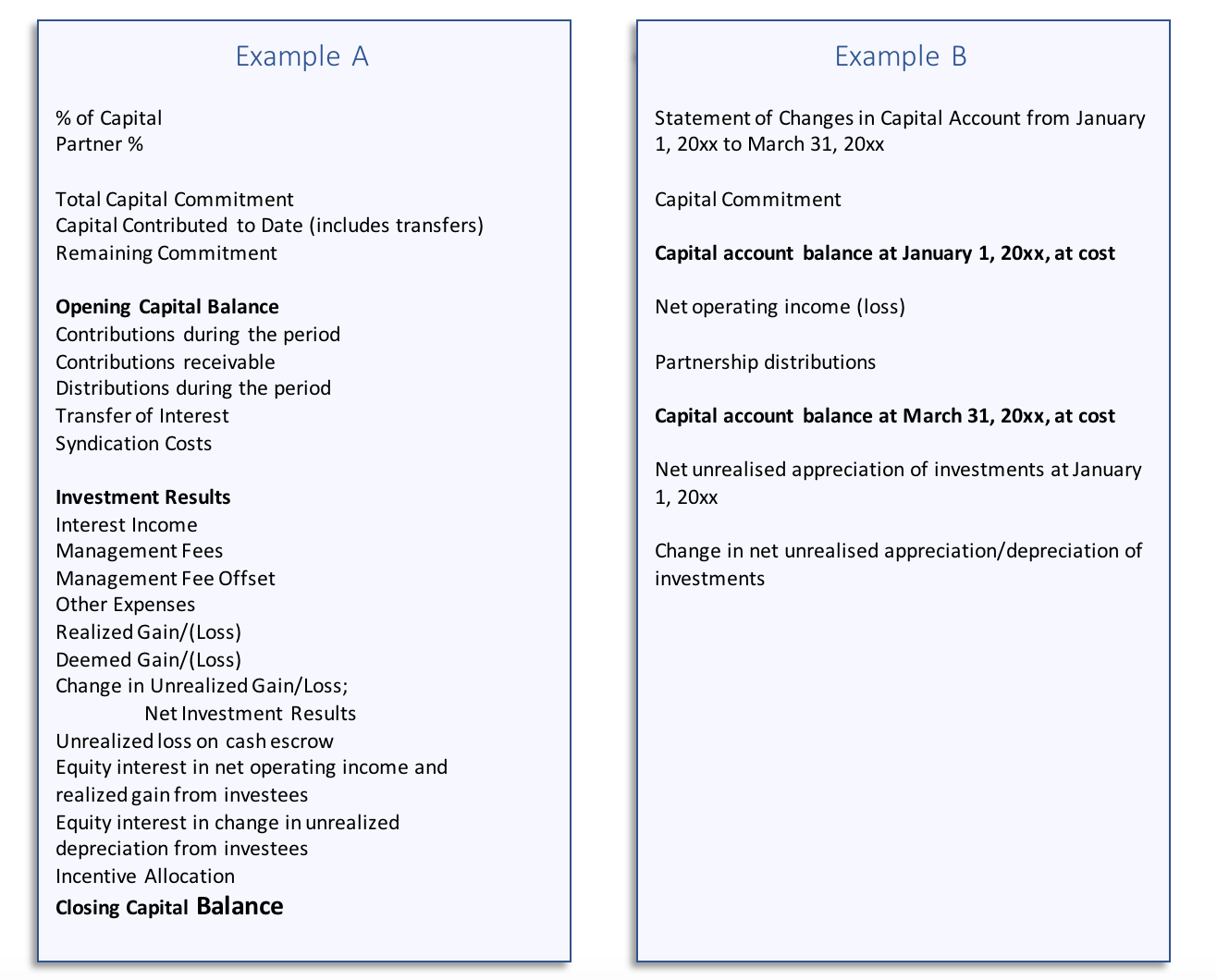

Automation is elusive because investor statement formats differ and the individual data points tend to be “apples to oranges” when it comes to comparability which hinders a simple data collection and aggregation. (See below for a comparison of two actual statement formats).

Banks, technology, and service providers have invested millions for PDF-scraping, AI, machine learning, and more to speed up the data collection and aggregation. However, incoming data needs an accepted global data standard (data tags) so that electronic reporting files can be automated easily and far more efficiently than PDFs or spreadsheets. The inefficiencies of the inputs, translate to uncertainty in the outputs.

Examples A and B are taken, line by line, from two private equity general partners’ (GPs’) quarterly capital account statements or “NAV statements” to their investors. Example A is very granular, while Example B is more summarised. Both statements communicate the same high-level information to the limited partner (LP). However, for example are they both net of allocated incentive (aka carried interest)? It is not clear in this example, and combining data from hundreds of different statements can make the same differences add up if the data is “apples-to-oranges”.

Examples A and B are taken, line by line, from two private equity general partners’ (GPs’) quarterly capital account statements or “NAV statements” to their investors. Example A is very granular, while Example B is more summarised. Both statements communicate the same high-level information to the limited partner (LP). However, for example are they both net of allocated incentive (aka carried interest)? It is not clear in this example, and combining data from hundreds of different statements can make the same differences add up if the data is “apples-to-oranges”.

Outgoing data

All pensions investing in private capital contend with the inefficiencies described above and then depending on their jurisdiction, their requirements for disclosure can vary just as much.

Working for a US public pension, I found that nearly every other public pension in the US had a slightly different approach to their disclosures.

US public pensions prepare comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) following the Governmental Accounting Standards Board guidelines, of course; however the disclosures for detailed investment costs were not specifically prescribed, and practices varied greatly.

A significant portion of my time each year was devoted to performing analysis and preparing responses to inaccurate comparisons of investment fees, incentive (such as carried interest), and expenses made in the press, reports, and research. Our operations team did an exceptional job of identifying management fees, allocated incentive and performance fees, as well as fund expenses but in the media, our fund was often portrayed as having substantially higher costs only because our disclosure was more transparent. The extra efforts were unavoidable but terribly inefficient.

The reality of inconsistency from incoming investment data and the different expectations for pension disclosures mixed with various disclosure practices among their peers creates a not-so-perfect storm for pensions. However, the Global Pension Transparency Benchmark’s launch[1] may be our industry lighthouse for disclosure practices, and the Adopting Data Standards Initiative seeks to solve for the incoming data hurdles. I am committed to both.

The Adopting Data Standards Initiative

ADS seeks to develop industry standards that will facilitate digital reporting in the free market for efficiency and transparency in the GP-LP relationship with an informed and realistic expected adoption timeline. The proposed ADS data standards (coming 2021-2022) in financial reporting will provide a solid foundation for the free market to solve for all market participants’ higher technology and analytical needs. ADS is a global non-profit, to develop #notanothertemplate, but electronic data reporting standards. Data standards can best be described as a common reporting language of data tags, or labels, and accepted definitions that the industry can utilise to exchange reports electronically in a consumable format that works with any commercial technology or platform: data interoperability.

Lorelei Graye, is president of the Adopting Data Standards Initiative and an advisory board member of the Global Pension Transparency Benchmark.