This is the fourth part in a series of six columns from WTW’s Thinking Ahead Institute exploring a new risk management framework for investment professionals, or what it calls ‘risk 2.0’. See other parts of the series here.

In this thought piece, we turn back in time – not to imagine how outcomes might have been different under a risk 2.0 framework, but to deepen our understanding of what this new mindset reveals. Because of path dependency, it is likely that a world trained in risk 2.0 would have even evolved along entirely different trajectories. So, rather than asking “what if?”, we ask “what can we learn?”

Our inquiry is guided by two questions:

- What new insights emerge when past crises are reinterpreted through the risk 2.0 mindset?

- How do these insights help us recognise the limitations of risk 1.0 and better prepare for the risks of the present and future?

Historical examples of significant market falls allow us to consider whether there are flaws in risk 1.0 thinking that resulted in the nature, likelihood and/or severity of these events being underestimated.

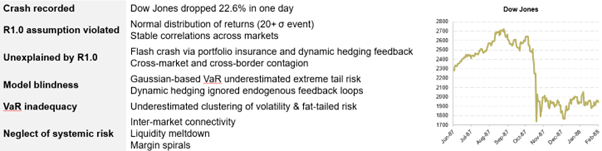

We applied a set of diagnostic criteria that exposed where traditional frameworks systematically fell short. These criteria were chosen because they highlight distinct but interlinked failures across assumptions, models, and system-level understanding:

- Crash recorded – describes the event which provides context for the testing framework that follows

- Risk 1.0 assumption violated – identifies the core theoretical assumptions that failed under stress (e.g., normal distributions, stable correlations, etc). It also highlights how simplifications embedded in risk 1.0 created blind spots under extreme conditions

- Unexplained by risk 1.0 – captures dynamics that risk 1.0 models could not account for (e.g., nonlinear feedback loops or contagion effects)

- Model blindness – reflects the inability of risk 1.0 models to adapt to emergent realities, leading to misplaced confidence in flawed measures. Demonstrates the disconnect between reductionist models and complex adaptive market behaviour

- VaR inadequacy – shows how VaR underestimated clustering, fat-tailed events, and compounding systemic pressures

- Neglect of systemic risk – exposes the absence of system-wide awareness in risk 1.0 (inter-market connectivity, liquidity spirals, contagion, etc)

Gaussian-based VaR models failed to anticipate extreme tail risks or the clustering of volatility that followed. Model blindness was exposed by confidence in reductionist models that ignored how collective actions could drive instability. Beneath it all lay a neglect of systemic risk: liquidity vanished, margin calls spiralled, and inter-market connectivity turned local stress into global contagion. Black Monday stands as an early warning of how complex dynamics can overwhelm static models – and why risk 2.0 demands adaptive, system-aware thinking.

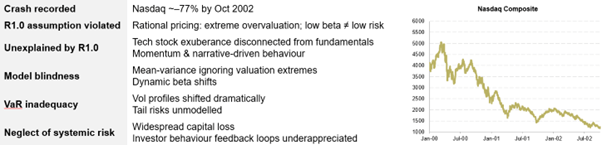

Through a risk 2.0 lens, the dot-com collapse reveals how belief in rational pricing masked deep behavioural and systemic distortions. By October 2002, the Nasdaq had fallen around 77%, exposing how risk 1.0 models equated low beta with low risk and ignored valuation extremes. Market exuberance became self-reinforcing, driven by momentum, narratives, and a collective faith in technological transformation.

Traditional mean-variance frameworks failed to capture how capital is concentrated in overvalued assets, nor how investor behaviour amplifies instability. Volatility regimes shifted abruptly, invalidating assumptions of stable risk premia, while VaR models ignored emerging tail risks.

The crash revealed feedback loops between capital loss, investor sentiment, and liquidity withdrawal – dynamics under-appreciated by risk 1.0.

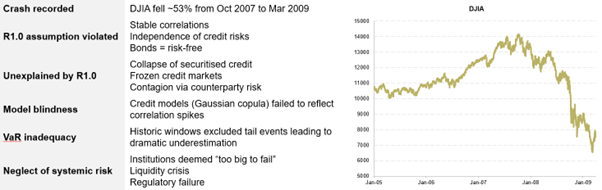

Viewed through a risk 2.0 lens, the Global Financial Crisis epitomises the collapse of risk 1.0 assumptions. Between October 2007 and March 2009, the Dow Jones fell roughly 53%, as beliefs in stable correlations and the independence of credit risks unravelled. Bonds once deemed risk-free became central nodes of systemic contagion.

Traditional models could not explain the freezing of credit markets or the cascading counterparty failures. The Gaussian copula framework missed correlation spikes and nonlinear stress dynamics. VaR, built on historical data, underestimated the magnitude and persistence of losses.

At the system level, “too big to fail” institutions turned from stabilisers to amplifiers, exposing the fragility of tightly coupled markets. Liquidity spirals and regulatory blind spots deepened contagion. The GFC became the germinal moment for the modern notion of systemic risk.

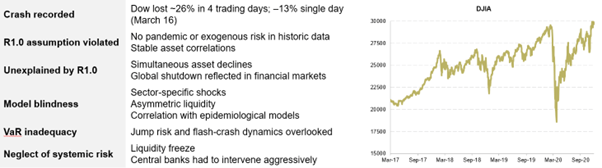

The COVID-19 shock was unlike anything risk 1.0 could imagine. In just four trading days, the Dow fell around 26% – including a 13% single-day drop on 16 March. No model built on historical financial data contained a pandemic scenario, and assumptions of stable correlations and sector diversification collapsed.

The simultaneous decline of risk assets worldwide reflected an economy in sudden global shutdown. Risk 1.0 models could not link epidemiological dynamics to market stress, nor capture the speed at which liquidity evaporated. Jump risk, flash-crash behaviour and asymmetric liquidity were all overlooked.

Like in other events considered, VaR frameworks underestimated both the magnitude and clustering of volatility, while systemic blind spots emerged as liquidity froze. Only massive central bank intervention prevented a broader financial seizure.

Seen through a risk 2.0 lens, the COVID crisis highlights how financial systems are deeply entangled with environmental, social, and real-world shocks.

The UK gilt crisis of 2022 revealed how even safe assets can become sources of systemic instability. Within six days, long-dated gilt yields rose about 1.5 percentage points, triggering margin calls and forced selling across LDI portfolios. Assumptions of stable rates, low volatility, and gilts as inherently low-risk assets collapsed almost overnight.

Traditional risk models failed to capture how rapid yield spikes could trigger collateral spirals and feedback loops between leveraged pension funds and the broader gilt market. Stress tests were anchored in mild historical scenarios, overlooking the extreme rate shocks of 2022.

The episode exposed the deep interconnections within the pension and LDI ecosystem – linkages under-recognised by risk 1.0. Only the Bank of England’s emergency gilt purchases prevented a full-scale liquidity crisis.

What can we learn?

Revisiting these crises through a risk 2.0 lens is not about judging the past, but about refreshing our field of vision. Each episode exposes how risk 1.0’s linear, model-centric view missed the adaptive, interconnected nature of real markets.

Risk 2.0 invites us to see and think in systems, shaped by behaviour, feedback, and design. Its strength lies less in prediction and more in awareness – the ability to recognise fragility before it becomes failure.

Andrea Caloisi is a researcher at the Thinking Ahead Institute at WTW.