Resilience has become the buzzword of our time. Literally, it’s ubiquitous, it’s everywhere. The French language has a less cerebral word for it – resilience is a passe-partout; it works well in every context.

The Latin resilire means “to bounce back,” and it’s no surprise that with the advent of industrialisation in the early 1800s, it came to denote the elasticity or power of materials to return to their original shape after being stressed (“bend, don’t break”).

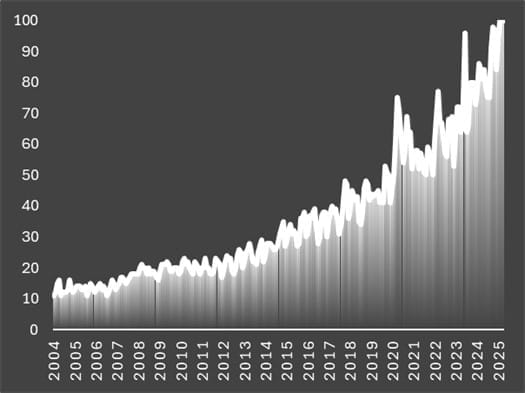

It remained confined to materials science for a while, entering psychology (to mean thriving despite challenges) only by the mid-1900s. By the 2000s, its evocative meaning had spread far and wide across various disciplines and contexts. The concept’s diffusion has grown tenfold since 2004, according to Google Trends.

There are likely many reasons behind the rise in interest in the concept. To us, one reason is particularly compelling because it provides a coherent macro picture: the system has become increasingly complex. Resilience, at its core, has a very defensive-reactive connotation and in a more complex world – with unprecedented pressure exerted on planet Earth – it makes perfect sense for humans to think about how to ‘bounce back’ from potential shocks ahead.

But there is no bouncing-back in the Anthropocene

We humans have become the dominant force shaping the planet, even to the point of outgrowing the biosphere [1]. We have grown so much that the emergent complexity is:

- eroding our agency, and

- amplifying systemic risk.

Consider perhaps the most systemic example – we feel increasingly vulnerable to climate change while simultaneously incapable of delivering the urgently needed reduction in global GHG emissions. We can recognise and verbalise what’s needed but struggle to enact it within the system.

So why are we struggling to enact the change that is needed? Either, because we believe the damage will not be so severe as to justify the cost of change. Or, because we believe our current system is resilient enough – sure, it will take some damage but we will change and adapt as we need to.

However science is warning us of irreversible tipping points and non-linear ripple effects within the broader ecosystem. In simple language, we may soon forget about the stable, normal (climate) state we thrived in.

Now, where are we expecting to bounce back from, or to, if irreversible states open out in front of us?

The concept of resilience assumes the recovery to some equilibrium trajectory or steady state at least, but climate change is a mean aversion process: “there is no mean, there is no average, there is no return to normal. It’s one way into the unknown”[2]. That’s definitely not an adaptable environment, let alone one where we could build an even better ‘bounced-back’ version of our system.

If it can’t be about recovery, it must be about transformation

Pointing to resilience in response to systemic risk means hoping for a mild systemic outcome – an inconvenient disruption while we repair the system. By implication, it means we are choosing to ignore the systemic outcomes which irreversibly break our system. And that means we are abdicating from the type of change we need – transformational or systemic change; in other words, at a minimum, abandoning our current economic system for a different one.

Resilience reveals unwavering faith in business as usual. We admit the ‘usual’ might be patched up here and there (eg leaving fossil fuels in the ground and going with wind and sunlight), but we don’t believe it needs to undergo any real test of transformation. It’s like anticipating potholes ahead, pulling over the car and replacing the tires and suspension, then getting back on the road – confident we’ll bounce our way through. But what if there’s no road left whatsoever to take us home? What if the only way forward is to rethink – or even entirely transform or ditch – our mode of transport?

As noted, resilience as a palatable concept has entered every imaginable human context, expanding our perceived capacity for determination and endurance in the face of adversity. The risk is that we forget that there is only one ultimate level of resilience that matters – planet Earth’s resilience.

What do we make of our cherished human resilience when one of the most internationally recognised scientists on global sustainability tells us that Earth is losing resilience?[3] Consider accelerating warming trends, record-breaking temperatures, unexpected anomalies, a potential shift in climate sensitivity, reductions in aerosol emissions, etc.

Resilience appears to be the quintessential form of adaptation when mitigation has failed. In other words, we will continue to tell each other about the greatness of human resilience so much that it will be the only strategy left to cope with climate change/systemic risk. But because recovery and adaptation without mitigation (a pillar of systems change) is doubtful at best, it will likely turn out to be an empty box in the face of a collapsing system.

Systems change demands the opposite: “break, don’t bend”

Let me wrap up with a play on words – for business as usual to continue, we need to bend without breaking. In this piece, I argued that the destabilisation caused by human activity on this planet, and the resulting climate change, leaves no room for bouncing back. Now, if we are to bend but not bounce, it likely means the bending will continue until we break – and that’s not what we want.

What we might actually want is to reasonably ditch business as usual and any tool that faithfully supports it, including the concept of resilience. We may want to break from business as usual and no longer compromise (bend) with a system that doesn’t work.

A system that simultaneously empowers and imperils us

I recently wrote about the Jevons paradox – or what I referred to as the “efficiency trap” – as an example of the double-edged dynamics that populate complex systems[4]. Similarly, human adaptability increasingly carries the seed of its own undoing. The following quote from Christopher Hitchens provocatively captures this idea: “We are an adaptable species and this adaptability has enabled us to survive. However, adaptability can also constitute a threat; we may become habituated to certain dangers and fail to recognize them until it’s too late”.

Andrea Caloisi is a researcher at the Thinking Ahead Institute at WTW, an innovation network of asset owners and asset managers committed to mobilising capital for a sustainable future.

[1] Human CO2 emissions weigh more than the biosphere and built mass (Global Carbon Project, Elhacham et al 2020)

[2] Mark Blyth, “There is no ‘getting back to normal’ with climate breakdown,” The Guardian, August 11, 2021

[3] Johan Rockstrom, Is the Earth losing resilience, and does it matter?, April 1 2025