1Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research: Guide to CRE Office Debt: Mapping exposures and analyzing property performance. As of April 17, 2023.

2Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. CRE: Will This Time Be Different?” Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. As of April 10, 2023.

3CMBS Weekly: Deconstructing and Demystifying US CRE Exposure,” BofA Global Research. As of April 21, 2023.

4 “Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales, 4th Quarter 2012,” U.S. Census Bureau press release. As of February 15, 2013.

5 “CMBS Weekly: Deconstructing and Demystifying US CRE Exposure,” BofA Global Research. As of April 21, 2023.

6 Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, “Global Economics Analyst The Lending and Growth Hit From Higher Deposit Rates”. As of April 5, 2023.

7Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, “US Economics Analyst: Small Banks, Small Business, and the Geography of Lending,”. As of April 10, 2023.

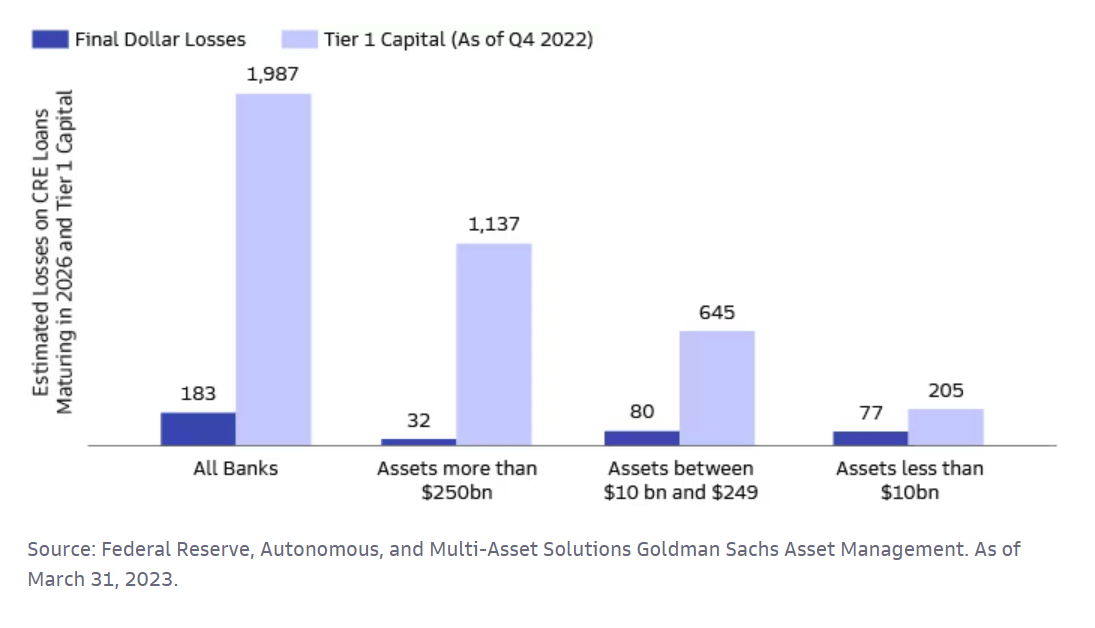

8US Federal Reserve, Autonomous and Goldman Sachs Asset Management Multi-Asset Solutions. As of March 31, 2023.

Disclosures

Risk Considerations

Investments in fixed income securities are subject to the risks associated with debt securities generally, including credit, liquidity, interest rate, prepayment and extension risk. Bond prices fluctuate inversely to changes in interest rates. Therefore, a general rise in interest rates can result in the decline in the bond’s price. The value of securities with variable and floating interest rates are generally less sensitive to interest rate changes than securities with fixed interest rates. Variable and floating rate securities may decline in value if interest rates do not move as expected. Conversely, variable and floating rate securities will not generally rise in value if market interest rates decline. Credit risk is the risk that an issuer will default on payments of interest and principal. Credit risk is higher when investing in high yield bonds, also known as junk bonds. Prepayment risk is the risk that the issuer of a security may pay off principal more quickly than originally anticipated. Extension risk is the risk that the issuer of a security may pay off principal more slowly than originally anticipated. All fixed income investments may be worth less than their original cost upon redemption or maturity.

When interest rates increase, fixed income securities will generally decline in value. Fluctuations in interest rates may also affect the yield and liquidity of fixed income securities.

Mortgage-related and other asset-backed securities are subject to credit/default, interest rate and certain additional risks, including extension risk (i.e., in periods of rising interest rates, issuers may pay principal later than expected) and prepayment risk (i.e., in periods of declining interest rates, issuers may pay principal more quickly than expected, causing the strategy to reinvest proceeds at lower prevailing interest rates).

An investment in Real Estate Investment Trusts (“REITs”) involves certain unique risks in addition to those risks associated with investing in the real estate industry in general. REITs whose underlying properties are focused in a particular industry or geographic region are also subject to risks affecting such industries and regions. The securities of REITs involve greater risks than those associated with larger, more established companies and may be subject to more abrupt or erratic price movements because of interest rate changes, economic conditions, tax code adjustments, and other factors.

General Disclosures

Economic and market forecasts presented herein reflect a series of assumptions and judgments as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change without notice. These forecasts do not take into account the specific investment objectives, restrictions, tax and financial situation or other needs of any specific client. Actual data will vary and may not be reflected here. These forecasts are subject to high levels of uncertainty that may affect actual performance. Accordingly, these forecasts should be viewed as merely representative of a broad range of possible outcomes. These forecasts are estimated, based on assumptions, and are subject to significant revision and may change materially as economic and market conditions change. Goldman Sachs has no obligation to provide updates or changes to these forecasts. Case studies and examples are for illustrative purposes only.

THIS MATERIAL DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER OR SOLICITATION IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE OR TO ANY PERSON TO WHOM IT WOULD BE UNAUTHORIZED OR UNLAWFUL TO DO SO.

Prospective investors should inform themselves as to any applicable legal requirements and taxation and exchange control regulations in the countries of their citizenship, residence or domicile which might be relevant.

This material is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or an offer or solicitation to buy or sell securities. This material is not intended to be used as a general guide to investing, or as a source of any specific investment recommendations, and makes no implied or express recommendations concerning the manner in which any client’s account should or would be handled, as appropriate investment strategies depend upon the client’s investment objectives.

Index Benchmarks

Indices are unmanaged. The figures for the index reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends, as applicable, but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Investors cannot invest directly in indices.

The indices referenced herein have been selected because they are well known, easily recognized by investors, and reflect those indices that the Investment Manager believes, in part based on industry practice, provide a suitable benchmark against which to evaluate the investment or broader market described herein.

This information discusses general market activity, industry or sector trends, or other broad-based economic, market or political conditions and should not be construed as research or investment advice. This material has been prepared by Goldman Sachs Asset Management and is not financial research nor a product of Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research (GIR). It was not prepared in compliance with applicable provisions of law designed to promote the independence of financial analysis and is not subject to a prohibition on trading following the distribution of financial research. The views and opinions expressed may differ from those of Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research or other departments or divisions of Goldman Sachs and its affiliates. Investors are urged to consult with their financial advisors before buying or selling any securities. This information may not be current and Goldman Sachs Asset Management has no obligation to provide any updates or changes.

Views and opinions expressed are for informational purposes only and do not constitute a recommendation by Goldman Sachs Asset Management to buy, sell, or hold any security. Views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation and may be subject to change, they should not be construed as investment advice.

Past performance does not guarantee future results, which may vary. The value of investments and the income derived from investments will fluctuate and can go down as well as up. A loss of principal may occur.

United Kingdom: In the United Kingdom, this material is a financial promotion and has been approved by Goldman Sachs Asset Management International, which is authorized and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority.

European Economic Area (EEA):This material is a financial promotion disseminated by Goldman Sachs Bank Europe SE, including through its authorised branches (“GSBE”). GSBE is a credit institution incorporated in Germany and, within the Single Supervisory Mechanism established between those Member States of the European Union whose official currency is the Euro, subject to direct prudential supervision by the European Central Bank and in other respects supervised by German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufischt, BaFin) and Deutsche Bundesbank.

Switzerland: For Qualified Investor use only – Not for distribution to general public. This is marketing material. This document is provided to you by Goldman Sachs Bank AG, Zürich. Any future contractual relationships will be entered into with affiliates of Goldman Sachs Bank AG, which are domiciled outside of Switzerland. We would like to remind you that foreign (Non-Swiss) legal and regulatory systems may not provide the same level of protection in relation to client confidentiality and data protection as offered to you by Swiss law.

Asia excluding Japan: Please note that neither Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Hong Kong) Limited (“GSAMHK”) or Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. (Company Number: 201329851H ) (“GSAMS”) nor any other entities involved in the Goldman Sachs Asset Management business that provide this material and information maintain any licenses, authorizations or registrations in Asia (other than Japan), except that it conducts businesses (subject to applicable local regulations) in and from the following jurisdictions: Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, India and China. This material has been issued for use in or from Hong Kong by Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Hong Kong) Limited, in or from Singapore by Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. (Company Number: 201329851H) and in or from Malaysia by Goldman Sachs (Malaysia) Sdn Berhad (880767W).

Australia: This material is distributed by Goldman Sachs Asset Management Australia Pty Ltd ABN 41 006 099 681, AFSL 228948 (‘GSAMA’) and is intended for viewing only by wholesale clients for the purposes of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). This document may not be distributed to retail clients in Australia (as that term is defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)) or to the general public. This document may not be reproduced or distributed to any person without the prior consent of GSAMA. To the extent that this document contains any statement which may be considered to be financial product advice in Australia under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), that advice is intended to be given to the intended recipient of this document only, being a wholesale client for the purposes of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Any advice provided in this document is provided by either of the following entities. They are exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence under the Corporations Act of Australia and therefore do not hold any Australian Financial Services Licences, and are regulated under their respective laws applicable to their jurisdictions, which differ from Australian laws. Any financial services given to any person by these entities by distributing this document in Australia are provided to such persons pursuant to the respective ASIC Class Orders and ASIC Instrument mentioned below.

* Goldman Sachs Asset Management, LP (GSAMLP), Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC (GSCo), pursuant ASIC Class Order 03/1100; regulated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission under US laws.

* Goldman Sachs Asset Management International (GSAMI), Goldman Sachs International (GSI), pursuant to ASIC Class Order 03/1099; regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority; GSI is also authorized by the Prudential Regulation Authority, and both entities are under UK laws.

* Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. (GSAMS), pursuant to ASIC Class Order 03/1102; regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore under Singaporean laws

* Goldman Sachs Asset Management (Hong Kong) Limited (GSAMHK), pursuant to ASIC Class Order 03/1103 and Goldman Sachs (Asia) LLC (GSALLC), pursuant to ASIC Instrument 04/0250; regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong under Hong Kong laws

No offer to acquire any interest in a fund or a financial product is being made to you in this document. If the interests or financial products do become available in the future, the offer may be arranged by GSAMA in accordance with section 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act. GSAMA holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 228948. Any offer will only be made in circumstances where disclosure is not required under Part 6D.2 of the Corporations Act or a product disclosure statement is not required to be given under Part 7.9 of the Corporations Act (as relevant).

Canada: This presentation has been communicated in Canada by GSAM LP, which is registered as a portfolio manager under securities legislation in all provinces of Canada and as a commodity trading manager under the commodity futures legislation of Ontario and as a derivatives adviser under the derivatives legislation of Quebec. GSAM LP is not registered to provide investment advisory or portfolio management services in respect of exchange-traded futures or options contracts in Manitoba and is not offering to provide such investment advisory or portfolio management services in Manitoba by delivery of this material.

Japan: This material has been issued or approved in Japan for the use of professional investors defined in Article 2 paragraph (31) of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Law by Goldman Sachs Asset Management Co., Ltd.

Bahrain: This material has not been reviewed by the Central Bank of Bahrain (CBB) and the CBB takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the statements or the information contained herein, or for the performance of the securities or related investment, nor shall the CBB have any liability to any person for damage or loss resulting from reliance on any statement or information contained herein. This material will not be issued, passed to, or made available to the public generally.

Kuwait: This material has not been approved for distribution in the State of Kuwait by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry or the Central Bank of Kuwait or any other relevant Kuwaiti government agency. The distribution of this material is, therefore, restricted in accordance with law no. 31 of 1990 and law no. 7 of 2010, as amended. No private or public offering of securities is being made in the State of Kuwait, and no agreement relating to the sale of any securities will be concluded in the State of Kuwait. No marketing, solicitation or inducement activities are being used to offer or market securities in the State of Kuwait.

Oman: The Capital Market Authority of the Sultanate of Oman (the “CMA”) is not liable for the correctness or adequacy of information provided in this document or for identifying whether or not the services contemplated within this document are appropriate investment for a potential investor. The CMA shall also not be liable for any damage or loss resulting from reliance placed on the document.

Qatar: This document has not been, and will not be, registered with or reviewed or approved by the Qatar Financial Markets Authority, the Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority or Qatar Central Bank and may not be publicly distributed. It is not for general circulation in the State of Qatar and may not be reproduced or used for any other purpose.

Saudi Arabia: The Capital Market Authority does not make any representation as to the accuracy or completeness of this document, and expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss arising from, or incurred in reliance upon, any part of this document. If you do not understand the contents of this document you should consult an authorised financial adviser.

These materials are presented to you by Goldman Sachs Saudi Arabia Company (“GSSA”). GSSA is authorised and regulated by the Capital Market Authority (“CMA”) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. GSSA is subject to relevant CMA rules and guidance, details of which can be found on the CMA’s website at www.cma.org.sa.

The CMA does not make any representation as to the accuracy or completeness of these materials, and expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss arising from, or incurred in reliance upon, any part of these materials. If you do not understand the contents of these materials, you should consult an authorised financial adviser.

United Arab Emirates: This document has not been approved by, or filed with the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates or the Securities and Commodities Authority. If you do not understand the contents of this document, you should consult with a financial advisor.

South Africa: Goldman Sachs Asset Management International is authorised by the Financial Services Board of South Africa as a financial services provider.

Israel: This document has not been, and will not be, registered with or reviewed or approved by the Israel Securities Authority (ISA”). It is not for general circulation in Israel and may not be reproduced or used for any other purpose. Goldman Sachs Asset Management International is not licensed to provide investment advisory or management services in Israel.

Jordan: The document has not been presented to, or approved by, the Jordanian Securities Commission or the Board for Regulating Transactions in Foreign Exchanges.

Colombia: Esta presentación no tiene el propósito o el efecto de iniciar, directa o indirectamente, la adquisición de un producto a prestación de un servicio por parte de Goldman Sachs Asset Management a residentes colombianos. Los productos y/o servicios de Goldman Sachs Asset Management no podrán ser ofrecidos ni promocionados en Colombia o a residentes Colombianos a menos que dicha oferta y promoción se lleve a cabo en cumplimiento del Decreto 2555 de 2010 y las otras reglas y regulaciones aplicables en materia de promoción de productos y/o servicios financieros y /o del mercado de valores en Colombia o a residentes colombianos.

Al recibir esta presentación, y en caso que se decida contactar a Goldman Sachs Asset Management, cada destinatario residente en Colombia reconoce y acepta que ha contactado a Goldman Sachs Asset Management por su propia iniciativa y no como resultado de cualquier promoción o publicidad por parte de Goldman Sachs Asset Management o cualquiera de sus agentes o representantes. Los residentes colombianos reconocen que (1) la recepción de esta presentación no constituye una solicitud de los productos y/o servicios de Goldman Sachs Asset Management, y (2) que no están recibiendo ninguna oferta o promoción directa o indirecta de productos y/o servicios financieros y/o del mercado de valores por parte de Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

Esta presentación es estrictamente privada y confidencial, y no podrá ser reproducida o utilizada para cualquier propósito diferente a la evaluación de una inversión potencial en los productos de Goldman Sachs Asset Management o la contratación de sus servicios por parte del destinatario de esta presentación, no podrá ser proporcionada a una persona diferente del destinatario de esta presentación

European Economic Area (EEA): This marketing communication is disseminated by Goldman Sachs Asset Management B.V., including through its branches (“GSAM BV”). GSAM BV is authorised and regulated by the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (Autoriteit Financiële Markten, Vijzelgracht 50, 1017 HS Amsterdam, The Netherlands) as an alternative investment fund manager (“AIFM”) as well as a manager of undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (“UCITS”). Under its licence as an AIFM, the Manager is authorized to provide the investment services of (i) reception and transmission of orders in financial instruments; (ii) portfolio management; and (iii) investment advice. Under its licence as a manager of UCITS, the Manager is authorized to provide the investment services of (i) portfolio management; and (ii) investment advice. Information about investor rights and collective redress mechanisms are available on www.gsam.com/responsible-investing (section Policies & Governance). Capital is at risk. Any claims arising out of or in connection with the terms and conditions of this disclaimer are governed by Dutch law. In Denmark and Sweden this material is a financial promotion disseminated by Goldman Sachs Bank Europe SE, including through its authorised branches (“GSBE”). GSBE is a credit institution incorporated in Germany and, within the Single Supervisory Mechanism established between those Member States of the European Union whose official currency is the Euro, subject to direct prudential supervision by the European Central Bank and in other respects supervised by German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufischt, BaFin) and Deutsche Bundesbank.

Japan: This material has been issued or approved in Japan for the use of professional investors defined in Article 2 paragraph (31) of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Law (“FIEL”). Also, Any description regarding investment strategies on collective investment scheme under Article 2 paragraph (2) item 5 or item 6 of FIEL has been approved only for Qualified Institutional Investors defined in Article 10 of Cabinet Office Ordinance of Definitions under Article 2 of FIEL.

321743-OTU-1824161