In a market where the number of products with an ESG or impact label are soaring, expert impact investment consultants, Ben Thornley and Jane Bieneman, outline best practice processes for due diligence and monitoring to guide investors to more precise impact labeling and stronger impact management practices.

“A fund’s name is often one of the most important pieces of information that investors use in selecting a fund,” said SEC Chairman Gary Gensler in recent remarks about a new set of proposed rules aimed at tackling misleading or deceptive fund names.

Many asset owners are well aware of the challenges of differentiating between the growing number and variety of institutional-quality products coming to market with an “ESG” or “impact”-sounding label.

According to one estimate, there are at least 800 registered funds in the US alone, with more than $3 trillion in combined assets, that claim to be committed to achieving certain ESG or impact goals. In a 2020 survey from the GIIN, two-thirds of respondents named “impact washing” as the top impact investing challenge facing the market. Regulators are increasingly concerned about the integrity and transparency of impact-labeled products, with rules currently in development to ensure that fund managers disclose their approach to ESG or impact and are able to back up their claims.

The question raised by each of these developments is how to determine which funds are authentic in their impact commitments, and which are most likely to achieve their social or environmental goals.

Asset owners with a track record of making impact investments are actively building dedicated teams and tools to answer this question. The Tideline team has worked with a number of these pioneering allocators, helping to establish industry best practices that other investors can learn from in their own journeys as impact investors.

We have found that impact funds typically undergo standard financial diligence and, in parallel, a two-fold process to: (1) determine the appropriate sustainability classification and whether the “impact” label is being properly applied; and (2) assess the robustness of a manager’s impact claims and practices.

This article explores these two processes in more detail to offer the investment community a guide for more precise impact labeling and stronger impact management practices.

What is an impact fund?

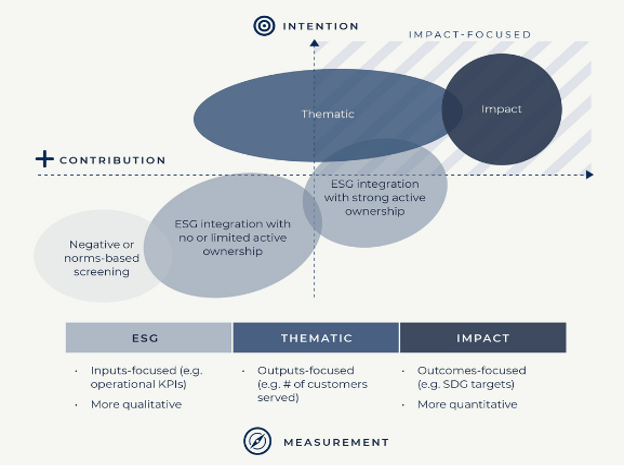

While there is no singular approach to identifying an authentic “impact investment,” it is helpful to anchor the definition in the three “pillars” of impact investing: intention, contribution, and measurement.

An “impact investment” is generally accepted as having a high degree of:

• Intentionality – Explicitly targeting social or environmental outcomes alongside financial returns, such as the UN Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs);

• Contribution – Playing a differentiated role to enhance the achievement of the targeted social or environmental outcomes; and

• Measurement – Monitoring and reporting impact performance based on measurable inputs, outputs and outcomes.

This breakdown aligns well with the SEC’s proposed labeling and disclosure system in the US, with impact strategies clearly differentiated from ESG-integrated strategies and ESG-focused strategies due to their intention to achieve a specific ESG impact. Impact funds would also be expected to disclose how the fund measures progress towards the specific impact, including the KPIs used and the relationship between the intended impact and financial return.

Experienced asset owners are looking for similar levels of transparency and disclosure.

To assess intentionality, LPs are asking questions like: “Which SDGs are the focus of the fund’s impact strategy? Does the strategy target very precise social or environmental outcomes or broad-based positive results?”

To understand contribution, investors are interested in the manager’s efforts to enhance impact performance, such as by engaging directly with investees or by providing relatively scarce capital.

Impact measurement might be assessed by asking: “Which types of KPIs will be reported? Does the approach focus on ESG factors (e.g., whether a microfinance institution follows market standards related to responsible lending), or impact outputs (e.g., the number of microfinance loans issued), or outcomes (e.g., quality of life improvements resulting from having received a microfinance loan)?”

A strategy high on intention, contribution and measurement would be appropriately labeled an impact investment. We have found that these core characteristics are also useful to identify ESG and other sustainability-related products. As described in Tideline’s recent report, “Truth in Impact: A Guide to Using the Impact Investment Label”, we have been using a labeling framework with clients for several years built on the understanding that each pillar can be independently dialed up or down for a particular strategy, providing a way to differentiate among sustainable investments more broadly.

Tideline’s Framework for Impact Labeling

For example, a renewables investor may have a clear goal of mitigating climate change by reducing carbon emissions (i.e., a high level of intention), but take a somewhat passive approach to engaging with management on the topic (i.e., a low or medium degree of contribution). Using our framework, that strategy would be labeled a “thematic” rather than an “impact” investment – a very important distinction for allocators to understand.

Tideline’s labeling framework also recognizes that, when asset owners say they are looking for investments with impact, they are often seeking a broader set of “impact-focused” opportunities encompassing of certain ESG and thematic approaches, as well as more narrowly defined “impact investments”.

While LPs may be interested in the larger universe of sustainable investments, however, they still want clarity on the impact approach they are investing in, including the specific social or environmental outcomes expected and how they will be achieved. For example, the pioneering work of PGGM is a useful model of an exacting approach to impact classification. PGGM mapped its entire portfolio to the Avoid-Benefit-Contribute (ABC) Framework developed by the Impact Management Project (IMP), which distinguishes a manager’s intentions to broadly avoid harm, to benefit the full range of a company’s stakeholders generally, and/or to contribute to specific and measurable sustainability solutions.

How are impact practices assessed?

The second step to underwriting an impact fund requires a tool akin to a scorecard.

Tideline has developed many of these impact rating mechanisms and, while each differs based on an asset owner’s unique goals and processes, they often boil down to an examination of impact strategies and practices.

Impact strategy considerations might include: the link between the investment strategy and impact objectives, the evidence supporting that connection, and the alignment of impact objectives with specific targeted outcomes.

In a recent case study co-authored with Tideline, J.P. Morgan Private Bank outlined its criteria to evaluate underlying fund investments for its $150 million Global Impact Fund (GIF). To assess a manager’s “strategic intent,” one of four impact dimensions in its rating framework, GIF scores: measurability and alignment of a fund’s impact objectives with GIF’s priority impact themes (30%); robustness of the evidence base supporting the manager’s impact objectives (40%); and differentiated impact value-add (30%).

On the question of impact practices, this is where the market has achieved greatest consensus, converging on the Operating Principles for Impact Management (Impact Principles), a framework capturing best practices for managing impact throughout the investment process, such as having a consistent approach to comparing impact results across investments, aligning incentives with impact performance, and managing ESG and impact risks.

Verifications of alignment with the Impact Principles, such as those provided by Tideline’s sister company BlueMark, are helping reveal areas of strength as well as potential areas of improvement at a market level. By aggregating findings, we now have independent benchmarks to differentiate between “Leading Practices” and “Learning Practices” among different types of impact investors, which is a game changer in enhancing the market’s institutional viability.

For example, BlueMark’s research found that specialist impact-only asset managers (i.e., those only managing impact products) generally outperform diversified asset managers (i.e., those managing both impact and traditional funds) when it comes to managing for impact in the latter stages of the investment process, with stronger practices to ensure impact beyond exit and to systematically review impact performance and incorporate any lessons learned. (See BlueMark’s 2022 ‘Making the Mark’ report)

As for assessing impact performance, tools have been slower to emerge due to the difficulty of tracking and comparing impact performance across such a broad swath of potential KPIs (i.e., emissions reduced vs. jobs created). However, there is progress here also, led by organizations like the GIIN and BlueMark, the latter of which recently published its proposed ‘Key Elements of Impact Performance Reporting’ and is currently overseeing a pilot project with Impact Frontiers to verify GP alignment with these elements.

The hallmarks of a robust institutional investment market — consensus, consistency, and discipline – provide the necessary basis for benchmarking, transparency and accountability. With the benefit of an increasingly robust taxonomy for classification and the tools for assessing impact strategies, practices, and performance, asset owners will be well placed to invest for impact with confidence.

Ben Thornley is managing partner and Jane Bieneman is senior advisor at Tideline the specialist impact investment consultant.

Jane Bieneman will speak at the Top1000funds.com Sustainability in Practice event at Harvard University from September 13-15. The event is only open to asset owners.