This article is the third in a series about the recently released CFA Institute report, the Investment Professional of the Future. In the first article, we outlined the accelerating changes and disruption facing the investment management industry. And in the second, I shared a roadmap that investment professionals can use to navigate these disruptions.

Now we turn to a roadmap for investment firms. Specifically, the report recommends that firms enhance the employee experience, invest in empowering leadership, and become change-savvy.

Enhance the employee experience

Investment organizations that want to attract and retain outstanding professionals should develop a people-centered culture that makes employee well-being central to the firm’s practices and policies. As part of the research, 3,800 CFA Institute members and exam candidates were asked about which aspects of a company or organization is most important to them. The results are below.

The responses clearly demonstrate that investment professionals seek employers that can provide opportunities for both personal and professional growth, as 83 per cent of CFA Institute members and 89 per cent of exam candidates value firms that encourage and provide opportunities for training and development. Personal growth also embraces work-life integration, where new skills are valuable in both professional and personal situations. The second most important factor is working for an employer with an inclusive culture, meaning one that considers and appreciates their employees’ views and ideas.

The responses clearly demonstrate that investment professionals seek employers that can provide opportunities for both personal and professional growth, as 83 per cent of CFA Institute members and 89 per cent of exam candidates value firms that encourage and provide opportunities for training and development. Personal growth also embraces work-life integration, where new skills are valuable in both professional and personal situations. The second most important factor is working for an employer with an inclusive culture, meaning one that considers and appreciates their employees’ views and ideas.

Invest in empowering leaderships

In terms of leadership skills for the future, industry experts believe that the most important skill is the ability to articulate a vision and to motivate colleagues toward a shared purpose. A quickly changing environment makes this even more important, and communication is the key.

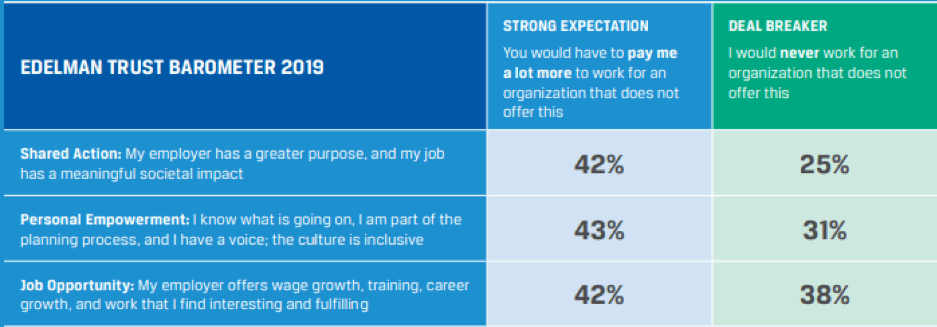

According to the 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer, employees across all industries have strong expectations that their jobs will provide purpose and have some meaningful societal impact, that their firm will have an inclusive culture where they have a voice in its planning and operations, and that their employer will provide opportunities for personal and professional growth. More than 40 per cent said they would need more financial compensation to give up any of these expectations, and about a third of those surveyed would never work for a firm that lacked these qualities.

These findings are relevant for investment organizations, which need more leaders and cultures that better engage the workforce. Specifically, employees, clients, and society more broadly are looking for leaders who:

These findings are relevant for investment organizations, which need more leaders and cultures that better engage the workforce. Specifically, employees, clients, and society more broadly are looking for leaders who:

- Speak out and communicate about the values important to stakeholders and other important issues that may be outside the boundaries of the business

- Speak with legitimacy within their area of knowledge and for appropriate stakeholders

- Are empathetic and understand who they are addressing

- Have the leadership courage necessary to convey the need for change and motivate others to facilitate it

- Are clear, consistent, and authentic about putting organizational values into action

It is particularly important that leaders are clear, empathetic, and sincere when communicating with employees about new topics that are becoming more important due to the continuous and increasingly rapid changes to the industry. This includes the future of work in the organization and in the industry.

Some roles and positions are likely to be displaced by technology and other disruptors, and employees will need guidance on how to approach the new working environment and ongoing career management. Firms must also be focused on their employees’ need for meaning and significance in their work. Employees want to work on teams and for firms where they are respected and where their contributions are noted and valued. Leaders must also have much higher levels of emotional intelligence to understand and revere the whole-life needs of employees.

Become change savvy

Just as individuals must become tech-savvy, organizations must be change-savvy. Our research found that the following are the largest concerns of industry leaders related to looming changes for investment professionals:

- Industry consolidation driven by streamlining and a focus on cost-cutting

- How artificial intelligence (AI) + human intelligence (HI) will require people to perform new roles and tasks and to perform traditional roles differently — and in some cases how AI will displace jobs

- The impact of technological and other industry changes on organizational culture

There is a high level of trepidation about how organizations will manage through these transitions or change their processes to leverage the human-machine collaboration.

Despite the level of unremitting change in the industry, the purpose of the investment industry will continue and concern itself with increasing the wealth and well-being of society, although the strategies and tools that firms use to realize it will vary significantly.

Bob Stammers, CFA, is the director of investor engagement at the CFA Institute and a member of the Future of Finance team at CFA Institute.