Aware Super, one of Australia’s largest superannuation funds, engaged McKinsey as part of the development of its next five-year strategy which the fund presented to the board in March. The fund is the product of fund mergers (First State Super, VicSuper and WA Super ) – a signature feature of the Australian pension marketplace. As it develops its next five-year plan a key initiative is how to deal with growth from an internal organisational perspective and in investments as it plans for an organisation that could double in size.

Chief investment officer, Damian Graham, is spending less time on investment strategy and financial market implications and more on organisational strategy and people management.

“It’s a lot about ensuring the investment function is well organised, is appropriately structured and that you have the right resources. It’s a lot about people management, organisational strategy and stakeholder management,” Graham says.

Indeed, it’s the shape and mechanics of Aware’s investment teams along with the fund’s approach to investment partnerships, the internalisation of certain investment functions as well as decisions around direct and co-investing partnerships where Graham has been spending a lot of time.

This plan will likely differ from other investment implementation plans designed by the group to date based on the fact it assumes the fund could be managing twice the amount of assets as the A$145 billion it has under administration today.

“As we move to A$200 billion and beyond we have to test our approach, structure and operating platform to support future growth,” Graham says . Aware is building an investment framework and strategy to comfortably accommodate A$300 billion by 2026.

Aware engaged consulting firm McKinsey to conduct a process which included discussions and comparisons with pension and sovereign funds around the world as part of constructing its five-year strategy which it delivered to its board in March. It is now working on the first phase of implementation.

“We wanted to test our operating platform and capabilities against global best practice to allow us to deliver strong returns on a long-term basis and to do it sustainably and at lower cost,” Graham explains.

Cost comes through scale, which will come organically as well as potentially inorganically via mergers and fund acquisitions, Graham acknowledges.

But cost can also be controlled through improvements to strategy and investment structures, he adds.

“We want to reduce cost to member materially… It is that duel objective of strong returns and also controlling the members costs,” Graham says, highlighting that Aware’s most popular MySuper growth option currently costs members in the low 70 basis points.

Pushing further down the path of internalisation will result in efficiencies for the fund, a feature of Aware’s five-year plan, Graham explains.

Internalising continues

Aware has a plan to increase the proportion of its internally managed assets from 20 per cent currently to 40 per cent across all of its portfolios in the next five-years at a time when it is also factoring in the potential doubling of total assets.

Identifying the fund’s strengths and competitive advantages has taken up a large part of Graham’s thinking and strategic planning, he says.

Local credit and direct lending, systematic equities investing as well as private equity co-investment are areas Aware will continue to focus on bringing expertise inhouse for as the execution of the five-year plan continues to play out.

Direct lending or ‘credit income’ as well as low-grade credit is an area the fund is focusing its internalisation capabilities on alongside the co-investment and co-lending relationships it is working on overseas.

It’s systematic equities project which it engaged HSBC on two-years ago will continue to help Aware build out its internal IP. Graham won’t be drawn on a “natural endpoint” for this project outside of highlighting that the mandate will eventually revert internally at some point in the future.

Infrastructure has been an area Aware has established internal expertise in, Graham acknowledges. He adds that private equity will be another area Aware will continue to push into co-investment relationships.

“I think we have a good capacity to manage complexity in our organisation. We want to continue to have flexible mandates which enable us to take on additional complexity to trade that for price paid,” he says.

“We have been happy to buy assets we need to develop or a business model for which we need to implement to create value. That additional complexity is a good trade off to get you a better return but not in every asset class,” he says.

Active management still lives here

The increasing focus on performance comparisons in the Australian market won’t be the death of active and fundamental management, according to Graham, however he added that funds will likely need to periodically adapt their approach to taking on risk.

“If you’re in the situation where you are at risk of failure of the performance test, clearly in the period before you’ll be considering what you do with active risk and there may be a way of changing the active risk in your portfolio to reduce the risk of failure and that will be a natural consideration the fund will need to go through,” he says.

“I don’t think this will kill active management, but at points in time you will need to consider active risk and need to change that.”

The balanced growth fund of Aware Super has returned 7.15 per cent over the 10 years to May 31, 2021.

When it comes to the evolving role of CIO as the country’s largest funds evolve into ‘mega’ funds, Graham puts it this way: “I try to keep somewhat of a good eye on markets, the investment decision making and frame work I keep involved in but not overly involved in,” he says, before adding that risk culture and governance rests with him in the Financial Accountability regime.

Graham is still at weekly investment meetings where all the main investment decisions are made but he concedes that a lot of the day to day decisions will go back to people responsible for the individual portfolios.

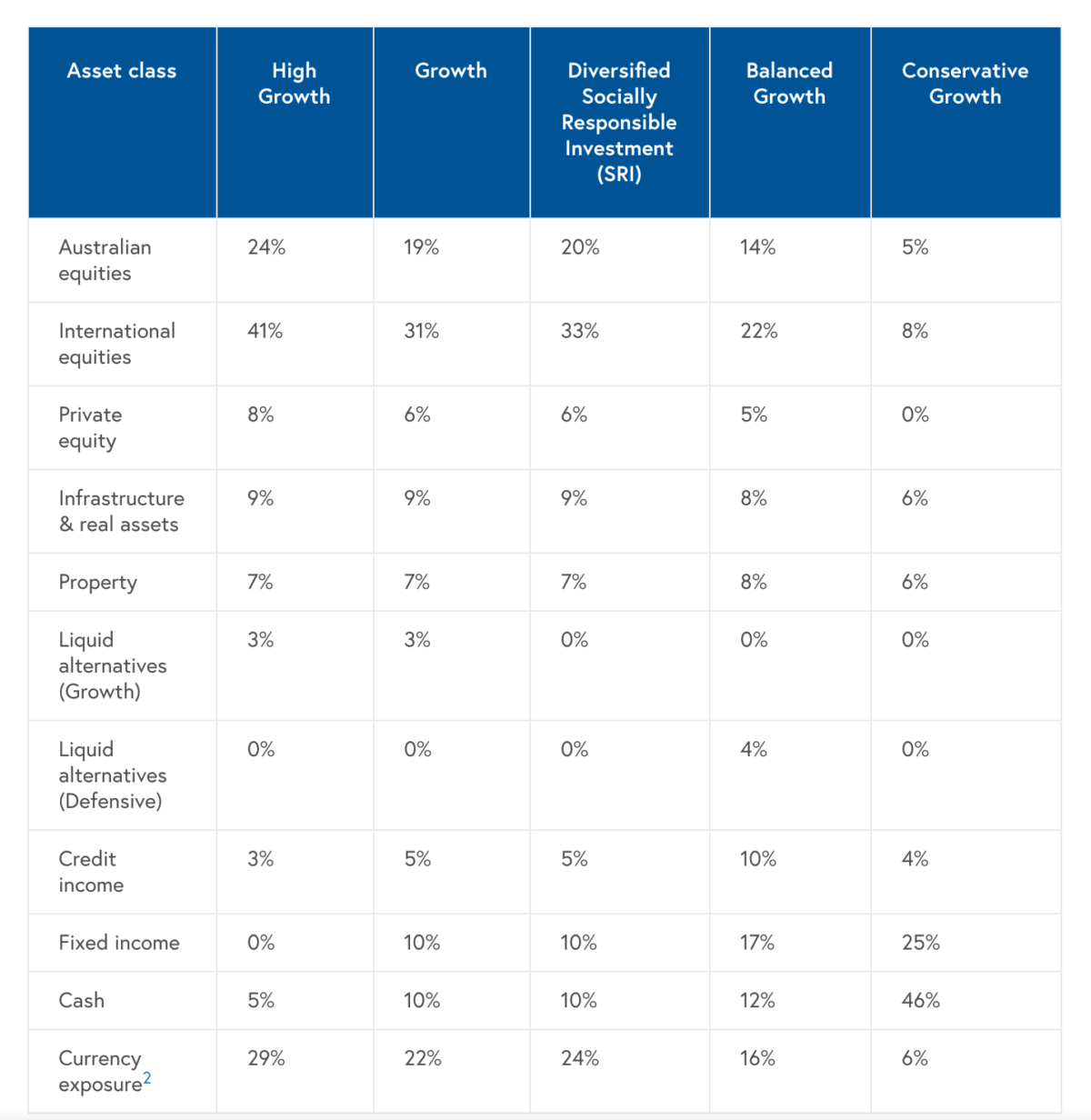

Aware Super Strategic Asset Allocation