Robert ‘Vince’ Smith, chief investment officer of the $21.5 billion New Mexico State Investment Council since 2010, believes turbulent times lie ahead, and he’s getting ready.

Smith has shaped strategy at NMSIC around protecting the fund from the high prices in traditional investment markets – and the lower rates of return that they promise in years to come. The fund calculates its valuations according to the cyclically adjusted price earning (CAPE) ratio, developed by celebrated Yale professor of economics Robert Shiller.

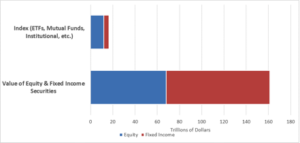

The real over-valuation this metric reveals, by comparing today’s prices with the 10-year moving average of historical earnings, is ringing alarm bells with Smith: stocks and bonds have rarely been priced so highly at the same time over the last 100 years.

“We are seeing stocks priced at the 95th percentile, so they have only been more expensive than they currently are 5 per cent of the time back to the late 1800s,” he explains. “We are also seeing fixed-income markets around the 90th percentile, so yields are very low relative to typical yields over time. [These situations usually] doesn’t happen together. Normally, if we see expensive stocks, we see cheap bonds and vice versa.”

He lays the blame at the door of central bank monetary policy.

“The low interest rate environment central banks have engineered is materially responsible for the high valuations in many markets.”

The US Federal Reserve raised rates in December 2015 for the first time in a decade, and although it has raised rates three times since, they remain historically low, in a range of 1 to 1.25 per cent, well below forecasts for 2017.

Smith’s response has been multipronged. He has steadily reduced equity exposure; the portfolio is now 40 per cent equities – equally split between US and non-US – 24 per cent fixed-income and 12 per cent each to private equity, real estate and real return. This contrasts with 2010, when the fund had a 60 per cent allocation to public equity, combined with equity-centric, opportunistic and credit strategies across real estate and fixed income.

Only a big sell off in US equities would make him rethink increasing the current allocation.

“Our publicly traded equity exposure is at a level that makes sense for now,” Smith says. “Here, at these valuations, we are comfortable with a more diversified portfolio.”

Smith has also switched 60 per cent of the US public equity allocation into diverse, factor-based strategies, away from cap-weighted benchmarks.

“We are avoiding the cap-weighted benchmarks because we think they are top heavy – as they usually get in late-stage equity bull markets.”

It’s also one way of diversifying away from the risk of the “huge multiples” of so-called FANG stocks, the acronym for tech stocks Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (via its parent, Alphabet), where valuations are, he believes, reminiscent of the late ’90s tech bubble.

Another 20 per cent of the US equity allocation lies in traditional active domestic equity strategies, where the focus is on value with downside protection, and using managers with strong performances in tough markets.

Donald Smith is a “favourite” small-cap manager here, along with Brown Brothers Harriman, which has a $600 million investment from NMSIC.

“We think they do a great job in tough markets,” Smith says.

The final 20 per cent of the US equity allocation remains in a cap-weighted index strategy.

An appetite for income producers

Smith has also steadily built up income-producing assets across energy, infrastructure, timber, farmland and real estate.

“High valuations can be managed by favouring investments that produce income as a large part of their total rate of return,” he says. “If we have two investments with similar expected rates of return, we’ll almost always take the one that has the higher component of income as part of that total rate of return over one that has a higher equity or capital-gain exposure.”

The real-estate portfolio is split between core real estate – where most of the return over a cycle comes from income – and value add and opportunistic investments, which are also biased towards income.

In private equity, this focus means a shift towards growth capital, investing with managers that improve margins at companies. These managers typically buy a company, increase its margins, then sell it on the basis of its higher earnings.

“It’s not dependent on a capital gain driven by revenue growth like public equities,” he explains. “We like this model more than the public-equity model, where an extra dollar of revenue is turned into a few cents of profit, and that additional profit gets capitalised and up goes the stock. Everywhere in the portfolio we are looking for ways to generate income and reduce dependence on growth-related capital gains for return.”

NMSIC expects to make $600 million in annual commitments over the next three to five years to reach the 12 per cent target for its private-equity portfolio.

Hello cash, goodbye absolute return portfolio

Smith’s crisis mitigation has also made him mindful of the need for cash. In a recent liquidity study, the fund looked into what kind of cash it would need on hand in a crisis market – something Smith defines as a time when stocks are down 35 per cent – to rebalance and meet capital calls. He also wanted to ensure a little in hand for opportunistic investments “if something really falls apart and we want to take advantage”. The process has resulted in NMSIC now ensuring 10 per cent of the fixed-income portfolio is liquid and available.

He has also just axed the absolute return portfolio. Despite acknowledging the work previous teams put in around the portfolio’s construction and strategy, Smith and his 11-member investment team reluctantly concluded it didn’t work.

“We took it out. Just this last month,” he says. “[It] has been a change on a par with our move away from equities – not in terms of dollars moved, but in terms of strategy. Seven years ago, we had a 10 per cent allocation in our funds-of-hedge-funds strategy. But it just wasn’t clear what it was doing, other than costing us a lot of money and delivering low returns.”

The few remaining hedge fund strategies – about 1 per cent of assets under management – won’t be in a bespoke portfolio but accessed through the non-core fixed-income allocation, where absolute return had the most success.

“It was difficult to find successful equity strategies, and macro funds weren’t putting up numbers that impressed us either. Most of the hedge funds we like have been in fixed income,” he says.

After a distinguished 30-year career in US public sector investment, Smith’s commitment and passion for public service is undimmed. He says nothing equals the reward of watching investment returns at the permanent endowment get ploughed back into the state.

“The tax-burden relief our investment income provides is the most impactful thing we do,” he enthuses. “Last year (ending June 2016), we distributed $900 million to the state that is mostly spent on education. That’s $900 million the tax base doesn’t have to come up with.”