For most investors recognising whether geopolitical tensions are a short term blip, or a long-term systemic shift is key to understanding how those risks inform investment decisions. Amanda White spoke to investors about the impact of geopolitical risk on their portfolios.

Most long term investors agree that geopolitical risks are generally small short-term blips. But how do they know when those short-term blips – like US/China trade negotiations or Brexit – turn into larger systemic problems or trends that will impact markets and investment fundamentals?

CIO of the A$140 billion ($98 billion) NSW Treasury Corporation (TCorp), Stewart Brentnall, says his job is “to consider on a dynamic ongoing basis whether our risk is correct in quantum and complexion to meet objectives”. Geopolitical risks are assessed alongside other risks in the consideration of whether an issue is material in depth or longevity, and Brentnall and the investment team have constant interaction with Brian Redican – the chief economist at the fund – who also meets with the investment committee on a regular basis. For them, the key challenge in assessing whether geopolitical risk will impact portfolio allocations is determining how sustained or long-lasting any particular risk is.

Similarly, Angela Rodell, chief executive of the $60 billion Alaska Permanent Fund says the challenge of geopolitical risk is determining how sustained or long-lasting any particular risk is and managing around it.

“We want to make sure we are not overreacting to short-term noise and taking advantage where we have conviction around any particular geography,” she says. “Geopolitical risk is one risk discussed with all the other risks an investment may have that are taken into account in making a decision,” she says.

“I think geopolitical issues have always been an important dimension to a global investment strategy and therefore you need to have views about what is happening in the world, where you want to be invested, where you do not want to be invested and how your risk profile changes as a result.”

In its geopolitical risk indicator Blackrock recently upgraded the risk around some specific threats namely global trade tensions, US-China relations, gulf tensions and European fragmentation risks.

Rodell says all of these risks will have an impact on the Alaska portfolio, and already have had an impact over the last couple of years.

“Since 2016 we have seen huge shifts in trade tensions, increasing tension with China, the Gulf continues to be a place of conflict and Brexit along with concerns about Italy impact the performance. The challenge for us as long-term investors is to find opportunity within these arenas and generate value for taking on certain geopolitical risks,” she says.

Brexit

Australia’s TCorp has listed equity index exposures in the UK and a number of unlisted investments including two airports, a gas distributor, water, and ports.

“We are actively engaged with most of the management teams of those investments, and we are very aware of those assets and their histories. They were all managed very diligently through GFC, and we have confidence in them. They are all long-term assets,” Brentnall says. For the most part he says it is business as usual with these long-term investments, despite the Brexit uncertainty. Although one threat is the impact of currency which he says could swamp the income generated from those investments.

For other funds, mostly those based in the UK or Europe, Brexit is less an opportunity, and more of a headache.

The giant Dutch fund, PGGM, for instance is still preparing for a no deal Brexit and is looking closely at how the regulations will hold. This throws up a whole bunch of operational issues including a close analysis of whether it can do business with UK asset managers, the impact on derivatives paper it has in the UK, counterparty risks, and whether it can pay pensions to people who live in the UK?

The French sovereign wealth fund, Fonds de réserve pour les retraites, is also preparing for a no-deal Brexit. Executive director, Olivier Rousseau, says to manage a mandate for FRR, an asset manager must have a European passport, and as a consequence of Brexit, soft or hard, the UK asset managers will lose their passport.

For several months, FRR has been preparing for a no deal Brexit, which would imply the loss of the passport with immediate effect, by working closely with its UK asset managers in order to have them assign the investment management agreements to an European Economic Area entity.

Alaska’s Rodell believes certain political risks do create buying opportunities.

Nationalisation of assets is one political risk to avoid so some emerging and frontier markets are challenging, she says.

But, in terms of a buying opportunity, she says Brexit is creating interesting opportunities in the United Kingdom and Europe. Opportunities she views as a more tactical move.

“When the initial referendum took place and there was a vote to leave the EU, we were in a good time zone and could see the Asia market over reacting and so could take advantage of the short-term noise,” she says.

“We have some tactical accounts where we can move money very quickly. We can also convene pretty quickly on investment committee level too, and are talking to our active managers and discussing opportunities with them.”

Alaska has an investment policy set by the board with percentage allocation bands around each asset class. The investment team can move within those bands. In addition its governance allows investment of up to 1 per cent of the fund in a single manager without board approval. That’s about $600 million.

“It allows us to be nimble,” she says.

This was also demonstrated during the euro crisis in 2012, where the fund took advantage of undervaluations in certain Eurozone countries, investing in real estate in Spain and Portugal.

“We try to look at these advantages and think the value outweighs the potential risks,” Rodell says.

At the end of the day perhaps geopolitical risk is something not to baulk at.

“The unexpected is what makes markets, creates spreads and allows us to generate alpha,” she says.

China/US trade relationship

The NZ$40 billion ($27 billion), New Zealand Super is one of few investors that is a true long-term investor in that it doesn’t have liabilities to pay right now.

So as chief economist of NZ Super, Mike Frith, says long term trends and valuations are the only relevant measures in how it allocates investments.

“When we think about our allocation or strategy we are not trying to predict or front run market movements,” he says.

So when assessing geopolitical risk it is very much about the impact on the long term. To this end, Frith believes the US/China conundrum is not just about trade.

“These are two largest economies finding their place in the world, and most importantly they are coming from completely different places,” he says. “There will be ongoing flare- ups. As a result whatever happens will effect long term thinking but it will be slow.”

Frith says the biggest issue for asset owners looking at geopolitical risks is working out when something is fundamental and what the implications will be.

New Zealand reviews its reference portfolio every five years, with the next review in 2020, and this is where any big trends are picked up.

“We might miss the timing point on certain things but that doesn’t matter to us, we distinguish between short term blips and a long term shift,” he says.

Frith says that over the past 30 years not many, if any, geopolitical events and the subsequent short-term volatility of markets have led to any significant shift in markets.

Firth is watching the China/US situation and says if the trade issues have not been sorted out by the end of the year it will attract more serious attention.

“The China/US relations are not affecting us right now, but if it went on for 12-18 months we would expect there’d be some enduring effects on global growth and that would impact our forward looking earnings expectations,” Frith says. “The longer it plays out the more likely it will effect expectations.”

TCorp’s Redican agrees that it is important to distinguish the noise – such as Trump tweeting about tariffs and markets going up or down by 1 per cent – and the underlying signal.

While he agrees that this short-term activity does not have a meaningful impact on growth he does warn that that analysis can lead to complacency about the long term implications.

For example, he says, a protectionist route can lead to weaker productivity growth over the medium term and those impacts should be monitored.

He says the current tension is impacting the “natural order” and potentially changing the slope of growth.

“The underlying problem [between the US and China] that we think is more pervasive is the issue around intellectual property rights, IP transfer, and technological issues. This is the basis of the dispute, and it is hard to see a compromise that satisfies both sides, it’s a simmering issue,” Redican says. “The worst case scenario is a bifurcation in the global economy and the western world trades among itself and the east and china trades among itself.”

This would result in a massive step down in productivity and efficiency, and potentially increase the risk of military tension.

Like other investors, NZ Super does scenario modelling including, for example, the various iterations of the China/US relationship including a full trade war, and the impact of that on global growth and the fund’s direct exposures in China as well as its New Zealand assets.

“This can help identify exposures we might not have been aware of and allows portfolio managers to think a bit deeper,” Frith says.

Similarly, NZ Super has some strategies it invests in that look at dislocation in markets and whether there is an opportunity big enough to take advantage of, sometimes the driver is geopolitics.

“We are always nervous when our models don’t explain something, like populism,” he says. “But this is not the ultimate driver of markets.”

To invest or not to invest

Some pension funds, such as the $14.2 billion South Dakota Retirement System see investing in China as too risky, while others including Sweden’s SEK345 billion ($39.1 billion) AP2 are increasing investments with really good results.

Alaska’s Rodell believes there is a fundamental change taking place in the US/China relationship and recognising that helps inform investment decision-making.

“Knowing what is long term systemic change and what is short term noise is important and while we don’t have any more knowledge than anyone else on that front we think there is definitely a need to watch trends and how the market responds.

“US and China relations are definitely significant, and there are trade tensions, but we think the US and China are too large to let it flounder. The global economy doesn’t allow countries to throw up borders and say they are not playing,” she says.

Having said that Rodell acknowledges that it is important to recognise the world is a different place.

“You could say you don’t want exposure, or you could say China is an important trade partner with the US and so want to invest in China. You have to distinguish between the long-term shifts happening in terms of trade and then the individual noise of certain behaviours, like Trump leaving China a day early,” she says.

Alaska has exposure to China through A-shares and is looking at private market opportunities in infrastructure and technology.

“We believe that China will continue to be a place we want to have exposure and so we need to work to find long term value in strategies that are exposed to China, and while maintaining awareness of how trade talks evolve and the relationship changes, not allow short term volatility dissuade us from that conviction.”

Rodell says there is some mild concern around the US and its attitude to foreign investment and whether there will be a response by some countries that results in barriers to US dollar investments.

“Does China still want to attract USD? This is something to watch,” she says.

But perhaps a Bloomberg interview with CEO of the $1 trillion Norges Bank, Yngve Slyngstad, puts geopolitical risk this perspective for long term investors.

“We are invested in the UK with a long-term horizon. How much we will invest will not be changed depending on the results of this development [Brexit], if we look past this – 10, 20, 30 years – the UK will be an important economy in Europe, and it will remain in Europe. We expect business on that timeline to develop positively no matter the outcome.”

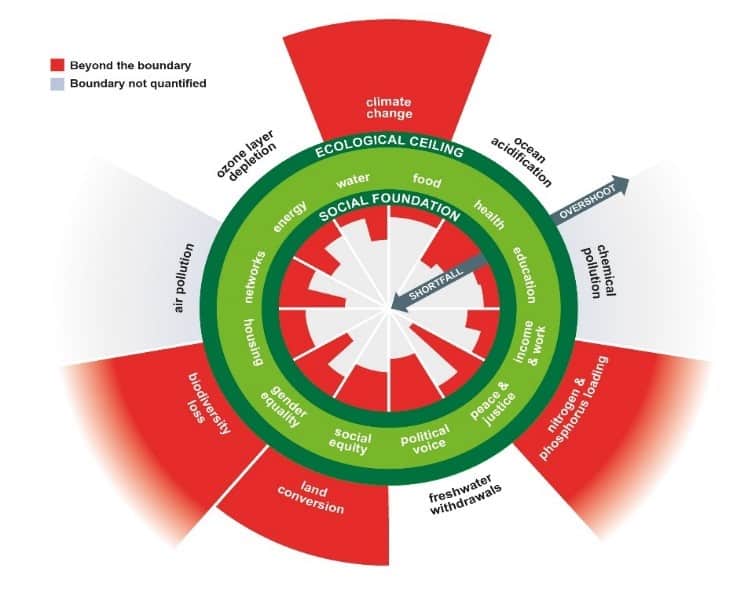

Source: Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth, 2017

Source: Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth, 2017