Mercer has quantified a ‘low-carbon transition’ premium in the sequel to its seminal climate change report, showing that a 2⁰C scenario equates to 11 basis points per annum to 2030 in a typical growth portfolio.

Further, investors with the same asset allocation but greater exposure to sustainability and the companies delivering the transition solutions, could expect to earn an additional 29 basis points per annum over the next 12 years if a 2°C scenario trajectory eventuates.

Quantifying alpha connected to particular climate change scenarios is fuel for investors to step up their efforts to protect their portfolios against climate change.

In Mercer’s new report, Investing in a Time of Climate Change —The Sequel, it analyses the potential impact of climate change on asset returns based on scenarios where global temperatures rose between 2⁰C and 4⁰C above pre-industrial levels by 2050.

The Sequel updates the ground-breaking 2015 report to take account of two global agreements: The Paris Climate Change Agreement and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The latest report concludes that for nearly all asset classes, regions and timeframes, a 2⁰C scenario leads to enhanced projected returns versus 3⁰C or 4⁰C and therefore a better outcome for investors.

While incumbent industries can suffer losses in a 2⁰C scenario, Mercer identifies many notable investment opportunities enabled in a low carbon transition.

Helga Birgden, the global leader of Mercer’s responsible investment team says the difference between the two reports is that the 2019 version models out to 2100.

She points out the updated modelling takes a much more positive view on the transition away from fossil fuels to a low-carbon economy.

“Most [pension fund] investors which have a growth asset allocation can expect 11 basis points per annum of additional returns to 2030 in a 2°C scenario and additional 29 basis points annually over the next 12 years,” adds Birgden.

“By 2050, climate change is a drag on returns in all scenarios.”

Sudden surprise

A new feature of the Mercer model is the ability to “stress test” the impact of sudden changes in scenario probabilities, and market valuations in the short term or shifts in the magnitude of physical damages in the long term.

But, from where Birgden sits, return impacts are unlikely to be neat and annualised. They are more likely to manifest as a sudden surprise.

In reality, she goes on to say, sudden changes impacts are more likely than neat, annual averages, so stress testing is an important tool in preparing for this eventuality.

“Stress testing portfolios for changes in view on scenario probability, market awareness and physical damage impacts can help investors to consider how longer-term return impacts that may appear small on an annual basis could emerge as more-meaningful shorter-term market repricing events.

“We see this occurring in markets all of the time. For example, it may be that there is a repricing event in insurance because of a hurricane or cyclone which according to our modelling will impact investor portfolios even within a year.

“Our stress testing model goes towards answering what it means now and what it will drive in terms of value loss and opportunity over the life of members, consumer’s savings,” she says.

Testing an increased probability of a 2°C scenario or a 4°C scenario with greater market awareness, even for the modelled diversified portfolios, results in a return impact of between +3 per cent and -3 per cent in less than a year, according to Mercer.

Mercer warns that returns across most asset classes will be affected by climate change.

However, at an aggregate level, the consultant expects developed market equities to be much less negatively impacted by the low-carbon transition than initially forecast but that interest-rate falls will see bond prices and returns rise.

“That said, on a relative basis, sustainability-themed equity is expected to benefit even further from a low-carbon transition, and emerging market equities are still expected to benefit from additional climate-finance support from developed countries,” the report notes.

Returns rise for renewables

The report underlines the negative sensitivity of real estate, infrastructure, agriculture and timberland to the impact of physical damages and resource availability.

Infrastructure on the other hand has a high positive exposure to transition risk due to a higher allocation to renewable assets in most portfolios, the report says.

While the consultant does not expect sovereign bonds to be sensitive to the climate change risk factors at an aggregate level, Mercer has identified Australia and New Zealand sovereigns as being sensitive to the impact of physical damages and resource scarce.

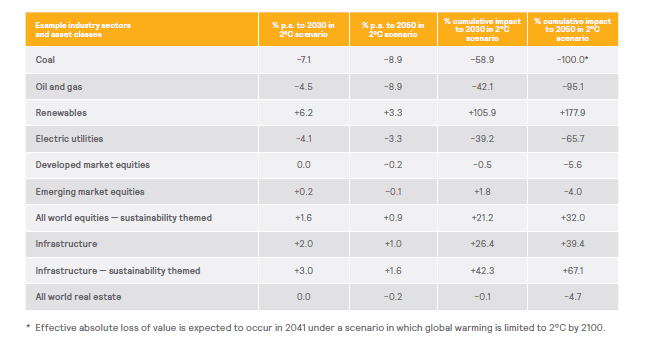

Unsurprisingly, the report shows that fossil fuel industries and on the flip side renewable energy are most sensitive.

The consultancy confirms that returns for cumulative renewables are forecast to rise by a stunning 105 per cent even as returns for coal will be down -60 per cent by 2030 in a 2⁰C scenario with oil and gas falling -42 per cent.

Incidentally, the positive impact on infrastructure at almost 23 per cent and sustainable equity at more than 5 per cent.