It is human nature to celebrate success. People love trophy ceremonies and hugs, confetti and high fives. Everyone loves a winner. The specter of “winning” associated with highly achieving firms in the investment industry, however, can be dangerous. Sometimes the intoxication of an extended period of laudable returns can lead to cultural apathy, lack of humility and reduced desire to innovate. This collective mindset can ultimately result in future woes.

Underperforming firms, in contrast, constantly seek new ways to create value, leverage innovation and force their way into the winner’s circle. CIOs responsible for investing on behalf of asset owners should recognise that underperforming firms could offer tremendous opportunities — especially when currently successful firms have become too comfortable with, well, winning. Below are five reasons why CIO’s should not overlook underperforming firms when seeking new avenues to invest an asset owner’s assets.

- The continued success fallacy

The investment industry is predisposed to viewing past success as an indicator of future success. Reasoning tells us that firms that have generated winning returns in the past have the talent, mindset and resources needed to generate high returns in the future. This bias, however, can be misleading. Continued success is never guaranteed in the investment industry, and could even be considered a liability. People are innately fallible, and investment firms are run by people — who are prone to the familiar trappings of success: apathy, entitlement, hubris and being lulled into complacency by the inertia of the past. The world is full of parables about the many perils of success, and human nature is always at the center of those failures.

The Chinese proverb “The spectators see more of the game than the players,” highlights the dangers of tunnel vision and why it is wise to consult outside opinions. Relying solely on proven resources can lead to an echo-chamber of the same strategies, attitudes and insights over time. The investment industry’s tendency to view past success as an indicator of future success is an understandable, but precarious, bias. Replicating effective strategies is a formula for obsolescence in an industry that is constantly evolving. In contrast, underperformers keenly aware of their shortcomings are always thinking about new opportunities on the horizon. Experienced CIOs who have witnessed the inherent dangers of presumed continued success are more inclined to value a focus on inventiveness and creating the future. Just look back at how much the investment industry has changed over the past 10 or 20 years. Change never stops.

- The complacency trap

CIOs must exercise due diligence on behalf of their stakeholders when evaluating the perceived benefits of working with currently successful investment firms. Complacency is a very strong and common psychological pitfall. After all, if the clients are happy and value is being created, why change? But complacency is deceptively quiet; it creeps in unnoticed over time, almost imperceptibly, and becomes part of a firm’s culture and operational routines. Complacency, as the byproduct of success, can masquerade as success itself and take root as soon as a firm begins patting itself on the back — and showcasing its latest industry awards beneath the bright lights of their lobby display box (you’ve seen them!).

The antidote to complacency is vigilance, humility and action. Investment firms must seek out groundbreaking or contrary ideas and learn to leverage evolving technologies and new regulations. Successful firms may ignore the inevitability and sweeping power of change because they are blinded by the glow of their current fortunes. What worked yesterday will certainly work today and probably tomorrow, they think. All investment firms, regardless of their prevailing circumstances, need to focus on what comes next. Firms that experiment with strategies and mechanisms that might give them a competitive advantage are more likely to stay ahead of change instead of chasing it. Investment firms with something to prove to themselves and the market, embrace change as opportunity.

- The client conundrum

Contented clients resist change for obvious reasons. Who in their right mind would change a strategy that is currently providing healthy returns? The onus to implement new strategies and a bold vision, therefore, falls on the investment firm. Educating clients today about future opportunities is key to winning tomorrow. An investment committee needs to be sure of its convictions if it wants to deviate from a historically lucrative path. Changing course and going out on a limb will be more difficult if the historic performance of the incumbent has been strong. The client conundrum constrains investment firms with the disadvantage of being trapped in a relationship that is inherently opposed to change. Underperformers, particularly less-established firms that are still making a name for themselves, tend to not have long-term clients, and therefore do not face the same obstacles. Not having to fight the gravitational pull of long-term success frees them to explore new or less traditional approaches to creating value. For investment firms that can only move as fast as their slowest parts, sometimes happy clients create headwinds that, in the long run, work against their interests.

- Timing Is everything

The investment industry is filled with firms that are at some point in their ascendancy or decline. CIOs, to effectively serve the asset owners that employ them, should strive to be as informed and insightful as possible with regard to timing. They must have the ability to read the tea leaves, so to speak, to identify where the most innovative ideas are coming from and know how to capitalize on those ideas before anyone else. Outperformers could be deceptively close to decline because they have realized their potential, and in an effort to maintain that success, have focused their energy inwards instead of outwards—which is where change and opportunities are born.

When determining the best investment strategies for their clients, CIOs should conduct qualitative, forward-looking assessments. The competitive edge could be found in underperformers who offer strategies that provide fresh perspectives. If a CIO waits too long to replace declining outperformers with ascendant underperformers, it could be too late to capitalize on the opportunities ahead. In this competitive industry, news regarding the “newest best thing” travels fast. Timing is key. CIOs who lack conviction can miss game-changing opportunities presented by lesser-known firms. In the famous words of financier James Goldsmith, “If you can see the bandwagon, it’s too late.”

- Evolving technology and AI

The investment industry is entering a new era of technological experimentation. There will be winners and losers; disruption from modern technologies like AI will be the norm. FinTech is revolutionizing the industry, and it is especially poised to catapult lean, tech-savvy underperformers into new spheres or relevance. CIOs will be increasingly tested on their understanding of how technologies, like blockchain, impact the future of the industry. AI and automation are progressively doing the work of actual people, which means outperforming firms with resource intensive products or services and aging operations are particularly vulnerable to change.

This charged atmosphere makes new, and maybe untested, investment firms more prone to seek out alternative sources of information and apply technology in new ways to derive value. Underperforming firms can also use new technologies to leapfrog into prominence, as the digital age has democratized access to information and resources. The history of investing teaches us that the future of the industry will come from unexpected places. Measures of past success such as assets under management and length of time running a particular strategy often counter-predict future success. To outperform through active management, CIOs need to consider underperformers who offer new, innovative strategies and mindsets. The digital transformation of the investment industry is underway and advancing rapidly.

Finally, it is human nature to seek the familiar and comfortable. The brand names and reputations of some outperforming firms may offer a reassuring and intangible sense of security. To compete, underperforming firms must offer forward-thinking strategies that differentiate their services from long-established rivals. That fight for survival is what drives innovation and change. And that survival instinct is what many of today’s successful firms can lose as a result of their good fortunes.

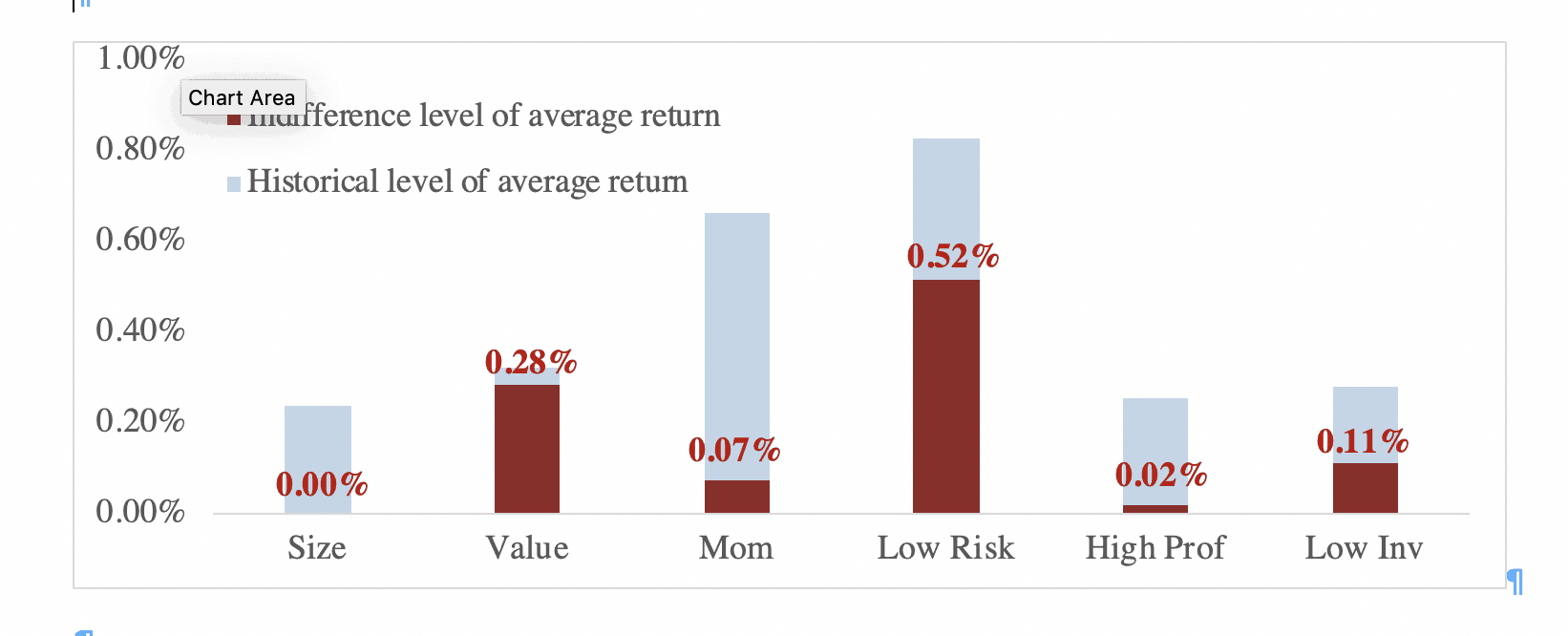

Why do some factors remain attractive after a sizable reduction of their premium? This is because such factors provide diversification benefits in addition to contributing to returns. A factor that provides strong diversification benefits will receive a positive weight, even if we assume that its premium is low. A low indifference premium thus reflects strong diversification benefits.

Why do some factors remain attractive after a sizable reduction of their premium? This is because such factors provide diversification benefits in addition to contributing to returns. A factor that provides strong diversification benefits will receive a positive weight, even if we assume that its premium is low. A low indifference premium thus reflects strong diversification benefits.