CEOs are accustomed to stretch targets and reward outcomes, not efforts says TIAA’s Thasunda Brown Duckett, the same principals should be applied in the DEI space. She was speaking alongside CIOs from CalPERS and CalSTRS at a diversity forum co-hosted by the funds.

TIAA chief executive Thasunda Brown Duckett said it’s hard to imagine that corporate America has made all the progress it can, given there’s only 41 female CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, with only two being African American.

Speaking at the CalPERS and CalSTRS 2021 diversity forum last week the new CEO also cited a study by McKinsey that documented how black Americans could collectively earn $220 billion less a year than white Americans.

But she maintained that part of the reason more DEI progress hadn’t been made might actually be well-meaning processes and policies that are getting in the way of accelerated progress.

“We don’t say we ‘tried our best’ to deliver… outcomes for our participants. That’s not how we even operate,” she said.

“We don’t even talk in that language. I do think we have to think about why are we talking in a whole different language [in the DEI space] that’s not even conducive to how we manage our business, it’s a foreign way that ultimately won’t drive… sustainable outcomes because we’re kind of code switching here. In terms of progress, I think we just have to operate it like we do everything else, which is tracking relentless drivers and measuring those outcomes.”

Brown Duckett, who heads up the $1.3 trillion US provider of financial services in the academic, research, medical, cultural and government fields, says she likes to call this “elevating with intention”.

“If we don’t really have that true mindset, then we will be able to excuse our way out of why there are not more women or underrepresented minorities in our pipeline.”

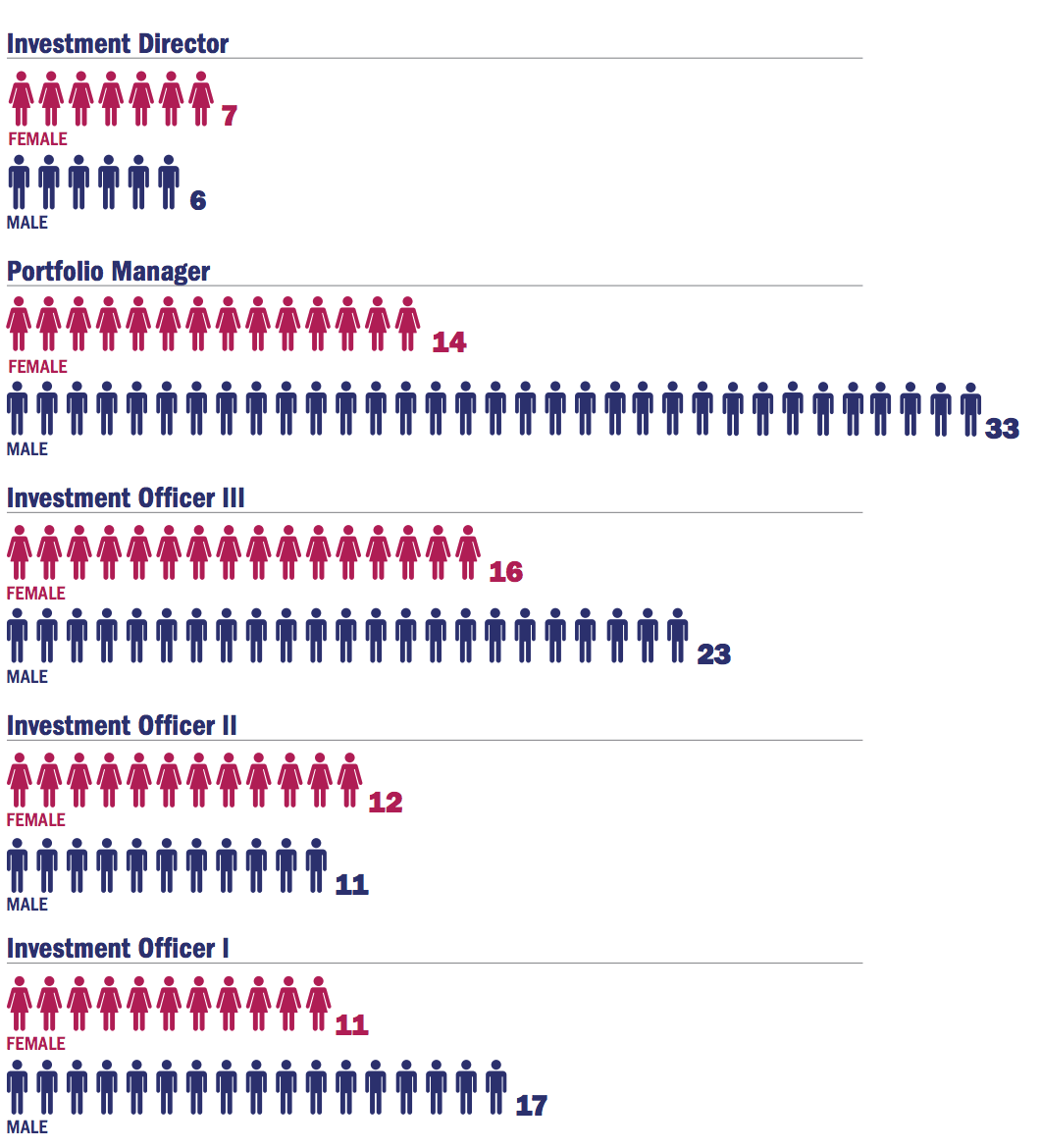

CalPERS‘ interim chief investment officer Dan Bienvenue speaking at the same conference was equally definitive about the need to measure performance but was also keen to point out that diversity held some of the answers to CalPERS’ key challenge, a challenge made all the more difficult in a low-rate environment.

“If I have to narrow the CalPERS’ challenge down to one thing, certainly for the investment office, it’s 7 per cent. Right?” he said.

“That’s our assumed rate of return. So how do we take $450 billion in assets, and expose them to a set of risks, investment risks, and try to earn a 7 per cent return over a multigenerational time horizon?”

“That speaks to the need for diversity and diverse perspectives. Because we never know where the best idea is going to come from, we never know where the smartest thought, the best way to structure our business, you name it. So we got to bring diverse perspectives to bear both internally within the investment team at CalPERS [and] the overall team at CalPERS. But then also this question certainly is one that many of our external asset managers and partners have heard me articulate, which is, if you were sitting in my chair, and this was your challenge, how would you do it? Again, bringing those really diverse perspectives to bear and then including them to the calculus is critical.”

CalSTRS‘ chief investment officer Chris Ailman said the tragic events of the last northern summer had really “woken up the country”.

“Now we’ve got lots of funds around the country who are raising this issue,” he said.

“And that’s critical. In the institutional investors like ourselves, they really now are paying attention. And they’re realizing that when they take a company public from private equity, it needs a diverse board, and that the way they recruit out of colleges is lacking, the way they promote people from within has been lacking. And I’m starting to see some really serious efforts… with a lot of the major GPs.”

“There has to be a shift in the process so that we can create space to be able to have access to the full talent”

Brown Duckett quoted a number of times the saying that “talent is distributed equally, opportunity is not”.

But she said for any real shift to occur in accessing talent from diverse sources there had to be a fundamental shift in the processes used to detect and, ultimately, hire it.

“We should not think about it as [if] we’re lowering the bar, because that is not what I’m saying. What I am saying is that there has to be a shift in the process so that we can create space to be able to have access to the full talent,” she said.

“And a real example is when we talk about best talent running P&L or running the bottom line. Maybe we don’t see as much diversity within the P&L lines of business today at mid management or upper [levels]. So maybe we need to say: who’s our talent and HR that [are] leading analytics, who’s our talent in other areas of the business? Where you do have a larger percentage of women or underrepresented minorities, and give them that shot, because they’ve proved that they can perform.”

Brown Duckett went on to say that while a company might make a strong commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion she saw the real question they had to ask themselves was how bold that commitment was?

“Did we just tally up what was already going to be? And it sounds like a really big number? Or do we really say, what is our outcome that we want to drive?” she said.

“And then when I think about being intentional about tracking the outcomes, this cannot be soft. We want to watch it like we do everything else, let’s look at the year-over-year growth, let’s have the accountability and understand the driver. And so again, when we’re thinking about the bold commitment, what outcomes will that drive that we think can be sustainable and create a real chasm shift? And then I would say that what matters is what the best result could be from the commitments we make.

“That’s that boldness.”

Brown Duckett, who took her position as CEO of TIAA in May this year, is the second Black woman currently leading a Fortune 500 firm, and just the fourth Black woman in history to serve as a Fortune 500 CEO. She’s the first woman to head TIAA.