Sustainability has long been a focus for Mercer. It is one of the five investment beliefs underpinning our advice and the firm established its responsible investment practice in 2004. The components of our sustainable investment beliefs articulate our conviction that:

- ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) factors can have a material impact on long-term outcomes and should be integrated into the investment process.

- Taking a broader and longer-term perspective on risk, including identifying sustainability themes and trends, will probably lead to improved risk management and new investment opportunities.

- Climate change poses a systemic risk, and investors should consider both the potential financial impacts of the associated transition to a low-carbon economy and the physical effects of different climate outcomes.

- Active ownership helps the realisation of long-term shareholder value by providing investors with an opportunity to enhance the value of companies and markets.

We continue to work with clients to embed these principles across their portfolios. In this article, we make the case for ESG integration and sustainability-themed investing.

We have been assessing portfolio managers on the extent to which they incorporate ESG issues and active ownership into their decision-making since 2008. The key aspect to our approach is to understand what decision-makers are doing at the strategy level to address ESG issues. Our ratings aim to capture the level of consistency with which ESG factors are assessed in the process and are a measure of intent.

ESG integration is about more holistically understanding the risks in a portfolio that are not necessarily readily apparent. In recent years, this has evolved to place greater emphasis on:

Climate change – Mercer’s study in 2015 on climate change at the asset class, industry, and total portfolio level highlighted the importance of taking a total portfolio approach to assessing climate risks. This has been reinforced by events such as the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement and the 2017 Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures’ (TCFD) recommendations for market participants to consider climate risks, apply consistent metrics and disclose related information in annual reporting. We are increasingly seeing managers incorporate climate change into their company assessments.

- Active ownership – There has been greater scrutiny of how asset managers are voting on shareholder resolutions and engaging with companies on climate change, diversity, food, water and other environmental and social issues at annual general meetings. For example, in the US in particular, the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility has found that climate change and inclusiveness/diversity were the top two areas of focus in shareholder resolutions in 2017. We expect these topics to remain priority areas.

- Social factors – More recently, the industry has turned its attention to the investment implications of social issues, with increased focus on areas such as social inequality, human and labour rights and slavery. While this is not yet apparent in manager approaches, we would expect this to become more prevalent as best practices are developed.

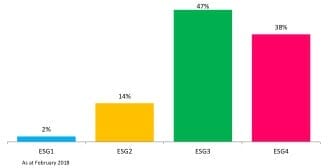

The extent to which portfolio managers integrate ESG and active ownership into their approach is reflected in our ratings. An ESG1-rated strategy is considered a leader; an ESG4-rated strategy is not. We take a similar approach for passively managed equity strategies, placing emphasis on active ownership at a central corporate governance level.

What is the opportunity set for strategies that integrate ESG?

We have seen good progress with asset managers since we started assessing ESG integration at the strategy level. In 2010, less than 9 per cent of investment strategies with an ESG rating were ESG1 or ESG2. At the beginning of 2018, more than 15 per cent of active investment strategies achieved a high rating. This highlights that there is still much room for improvement across the market.

We believe the trend will continue along a similar trajectory as asset managers develop their ESG programs at a firm-wide and investment strategy level, in response to increasing client demand, industry initiatives and regulation.

Over the last few years, we have seen more clients place a greater weight on ESG ratings when undertaking manager selections. The ratings can help identify managers who are genuinely integrating these factors and active ownership practices into their portfolio decision-making. We encourage clients to review the ESG ratings of their investment strategies regularly and aim for best-practice integration.

The investment case for sustainability

It’s not just about incorporating these intangible risks; it is also important for investors to capture the revenue prospects and opportunities sustainability themes present. Such themes aim to identify the growth opportunities of companies that provide solutions to environmental and social challenges. They can offer attractive opportunities, but can also enable clients to hedge portfolios against potential climate-change risks. Mercer’s research has demonstrated that exposure to sustainability-themed equities could improve the resilience of an overall portfolio across various climate-related scenarios. These themes tend to be under-appreciated or under-recognised by the market and, therefore, offer the potential for increased valuations over a long-term horizon.

More recently, there has been greater emphasis in the industry on investing with a social (and environmental) purpose across a range of asset classes and new approaches. This is driving further innovation. The Paris Agreement and the launch of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in 2015, are examples of this shift. The SDGs represent a huge business opportunity that can lead to disruptive change as market participants focus increasingly on holistic thinking and systems changes. Research the Business & Sustainable Development Commission published last year shows the 60 fastest-growing sustainable market opportunities related to delivering these goals could potentially generate revenues and savings of $12 trillion by 2030 and have the potential to create about 380 million jobs. More than half of these opportunities are based in emerging markets.

Furthermore, we believe the momentum the Paris Agreement has created around investment opportunities related to the transition to a low-carbon economy has only just begun. For example, research has shown that at the turn of this century, renewable energy represented less than one-fifth of total fuel sources, highlighting that we are in the early stages of this transition. We expect renewables to replace fossil fuels at an increasing pace, as countries increasingly look for and use new sources of energy.

Increasing opportunities in sustainability themes

From our perspective, the investment universe is growing rapidly. A number of long-term opportunities in sustainable themes can be accessed via private markets, ranging from renewable energy to water and waste management, sustainable resource management, environmental consultancies, and agriculture and timber. We have also seen innovative ideas emerging in other asset classes, such as: active listed equity strategies, in which portfolio managers are investing in companies positioned to address the SDGs; fixed income, through green bond strategies; and passively managed strategies tracking a broad range of low-carbon and ESG indices.

These themes represent a small subset of our global investment manager database (GIMD) but there appears to be significant interest from asset owners in understanding the evolving product set. GIMD houses more than 31,000 investment strategies across more than 6000 asset managers. Of this, only about 500 strategies (of institutional quality) have some specific sustainability focus within their investment philosophy. This means less than 2 per cent of all investment strategies listed in the Mercer database actively focus on the revenue opportunities provided by ESG themes. This highlights the diversification benefits of investing in sustainability themes and the opportunity set will continue to grow as demand increases.

Performance of sustainability-themed investments has varied and has tended to be driven by factors such as regulatory and political initiatives, the economic environment, and broad equity market movements, along with sector and style biases. Although the track records for sustainability-themed investment strategies are short relative to those in mainstream listed equities, the best of these strategies have the potential to outperform the broader market while offering diversification from the risk and return drivers underlying mainstream strategies. Over three and five years, performance of broad sustainability and niche themes has ranged widely, which highlights the importance of manager selection. Our focus is on identifying those managers and strategies we believe have the expertise and skillset to find those underappreciated ideas and the potential to outperform the broad market over an economic cycle.

Clients are increasingly allocating to these areas. Between 2014 and 2017, we undertook about three dozen manager selection exercises focused on sustainable approaches, with clients allocating or committing about $2 billion in capital across various asset classes. So far in 2018, we are undertaking a further half-dozen manager selections focused on sustainability themes. Although these are relatively small allocations, the growth potential is huge.

What’s next?

Where Mercer is implementing manager selection and portfolio construction on behalf of clients, we have developed a reporting framework to help them report to their beneficiaries. Our reporting on sustainability includes:

the level of exposure to sustainability themes

the ESG rating of the underlying investment strategy

a snapshot of how managers are engaging with companies and the key themes of engagement

portfolio carbon footprint analysis.

We are working towards implementing additional elements of the TCFD framework, and continue to enhance our modelling of climate change impact under various scenarios.

The SDGs are a framework and common language for mapping activities to the 17 goals and to identifying relevant underlying indicators. Investors are increasingly looking to employ this framework, as it has the potential to standardise the approach to impact investing. We continue to enhance our approach and apply this to a wider audience.

We encourage investors to begin their sustainability journey through updating their investment beliefs and policies to holistically incorporate ESG factors. In building an unconstrained strategy, we encourage clients to develop: an approach to integration of climate change among other ESG risks that incorporates scenario analysis; an active ownership program on their approach to engaging with companies and regulators; and a focus on themed investments (specifically allocating to solutions around environmental and social challenges). While investing sustainably might not yet be mainstream, the direction of travel is increasingly clear.

Sarika Goel is a manager research specialist at Mercer Responsible Investments.