The Irish pension system is set for major reform over the next few years. The general direction of this was set out in the Pensions Roadmap the government published this February. It involves changes to the state pension, the introduction of auto-enrolment and general simplification of the system, with greater emphasis on governance and reliance on master trusts. The European Pensions Directive – Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provision (IORP) II – also has to be transposed into law by January 2019. Some consultation papers has already been issued, with more imminent. We expect to see legislation in the autumn.

Like many systems, the Irish one is a multi-pillar approach. It features a basic state pension, supplementary occupational pensions and personal pensions. While individual employers can make joining a pension scheme compulsory, the general approach is voluntary. Employers have to provide only access to a pension, they do not have to pay contributions. The net result is that only 50 per cent of the workforce has any form of pension savings and will, therefore, be relying on the state for all their retirement income.

The state pension is now €243.40 ($277) a week and is paid to anyone who meets the eligibility requirements, which are based on the number of social insurance contributions paid over a working lifetime. Lower amounts are paid to people who don’t have the required social insurance contributions and there is a means-tested pension for those who don’t qualify for the main pension. It is paid from age 66 but from 2021 that increases to age 67 and the age will rise again, to 68, in 68. This is intended to link the state retirement age to improvements in life expectancy, with regular actuarial reviews.

All public-sector pensions in Ireland – including for central and local government, teachers, health staff and the police – are unfunded and operate on a pay-as-you-go basis. The liabilities of those schemes were recently valued at €114.5 billion ($130.5 billion)

The most recent Irish Association of Pension Funds investment survey, at the end of 2016, found that Irish occupational pension schemes comprised €125.5 billion ($142.7 billion) in pension savings. This was the highest value ever recorded and almost double the €63.5 billion ($72.4 billion) at the end of 2008. Assets in defined-benefit schemes amounted to just over €78 billion (88.9 billion) while defined-contribution schemes totalled €47.5 billion ($54.1 billion).

Shift out of equity

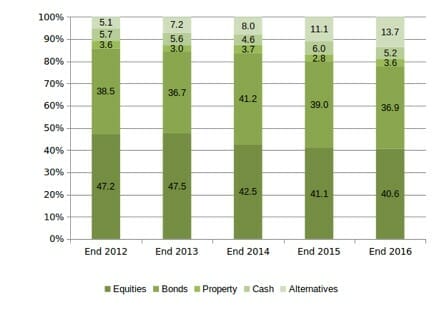

The shift away from equity allocations in DB schemes continues. Just over 40 per cent of assets are in equities and almost 37 per cent are in bonds. Alternatives now total 13.7 per cent compared with 5.1 per cent five years ago. This reflects a general “de-risking” of DB schemes, often under regulatory pressure.

Irish DB scheme asset allocation 2012-16

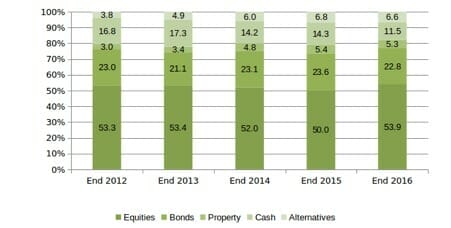

DC assets, in comparison, have a higher equity content but also a high bond allocation – 22.8 per cent. Some of this may be part of life styling strategies but it may also reflect more caution on behalf of individuals.

Irish DC scheme asset allocation 2012-16

Auto-enrolment

With just over half the workforce having any pension savings, the government has decided it is time to introduce auto-enrolment. The success of the UK system probably influenced this decision; however, it has been under discussion in Ireland for many years.

While the full details on how the system might work haven’t been published, the government has indicated that all employees over age 23 and earning more than €20,000 ($22,000) a year would be required to be enrolled in a pension arrangement by their employer. While contributions will probably be phased in, ultimately they will be on a matched basis: 6 per cent from the employer, 6 per cent from the employee and a 2 per cent government contribution, which will replace the current system of tax relief.

Individuals would be able to opt-out after nine months and there would also be an opt-in option for people not otherwise eligible, such as lower earners or the self-employed. The aim is to have contributions start by 2022. Will there be some state involvement or the equivalent of the UK’s National Employment Savings Trust? Or will there be approved providers as in New Zealand?

Professional trustees

The introduction of auto-enrolment will be a gamechanger but there are also regulatory shifts on the horizon, including IORP II and potential rules for master trusts. The directive focuses largely on cross-border schemes, governance and communications. The governance requirements will involve much more formalised focus on risk management and controls. All trustee boards will also have to have prescribed levels of professional qualifications and experience. This will probably mean that at least two trustees will have to satisfy each requirement.

While an increased focus on governance is welcome, it is important that there remains a place for member-nominated and lay trustees. While they may not have the prescribed experience and qualifications when they first become trustees, they do know the members of the scheme and understand the culture of the employer. These can be invaluable traits in determining what will and won’t work for the scheme and its members. Member trustees also have a strong sense of their responsibility towards their fellow members and this guides their decisions.

Master trusts can, in theory, produce better governance and lower costs, due to economies of scale but they don’t have the same connection with members, as they are from multiple employers and there is no direct link to the members. Also, employers often pick up administration and other costs in a DC scheme that, in a master trust, are usually just built into the charging structure. Getting the balance correct will be crucial to ensuring that members experience better outcomes, which should be the goal for everyone involved.

ESG emphasis

IORP II also requires trustees to disclose how they factor ESG considerations into their risk management and investment decision-making. This will be the first-time many trustees will have specifically considered this. While the requirement is relatively benign in that, for example, trustees could merely report that they don’t consider those issues, there are already plans to strengthen the requirements to force consideration and also gather the views of members.

There are many changes ahead for trustees and the role is getting more difficult. It is important that there be a good balance between effective governance and regulation and encouraging the involvement of trustees so that members receive the best outcomes possible.

Jerry Moriarty is chief executive of the Irish Association of Pension Funds, which represents pension savers in Ireland.