Why even good inclusion and diversity (I&D) policies will miss their mark unless corporates have a better understanding of their employees.

Well-trained company management often tout that employees are their most valuable asset, that people are at the heart of who they are and that they have a strong corporate culture.

However, interest by management is often fleeting (“employee engagement survey, anyone?”), focus and policies tend to be weak and emotional intelligence tends to be low, that is they deal with people in ways that de-motivate. The optimist in me would like to believe that it’s not that leadership teams do not care. It’s just that designing effective top-down policies beyond pay and benefits that the average employee really cares about is really hard to do, especially for large companies.

This problem is made worse by the fact that very few organisations actually know who their employees are outside of the usual metrics of 70 per cent junior/mid-level, 25 per cent senior and 5 per cent really very senior.

One of my favourite lunchtime hobbies is to read Work Tribes in the FT. From egomaniacs to altruists, from the ‘sponsor-me’ guy to the ‘superwoman’, this satirical series allows readers to ‘listen in’ on the conversations of various characters in the workplace. Work Tribes is a little bit funny and somewhat indelicate, but behind some of the outrageous comments by ‘co-workers’ is an important lesson: in our workplaces we are surrounded by a unique blend of potentially weird yet wonderful individuals. Organisations need to make more deliberate strides to understand the identity of their workforce as a very basic first step in designing sensible engagement and inclusion and diversity (I&D) programmes.

Who are you? An object lesson in identity

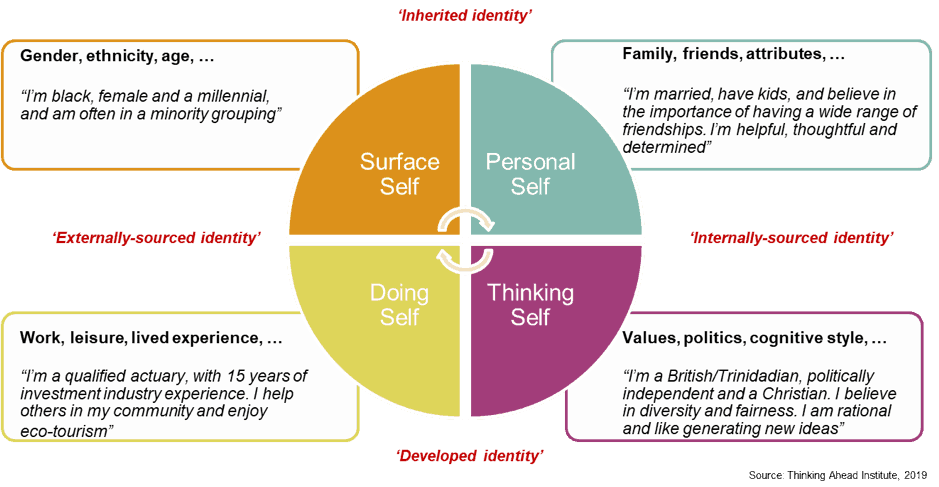

Imagine you are management and you have been asked to come up with some new I&D polices. You decide to be clever and sketch a map of the categories of individuals in your organisations. What does this map look like? While there are many more categories that one could add, we can view work identity as very broadly made up of four basic ‘selfs’ (and if you dislike these labels, please substitute your own – you’re management after all).

- Surface self: this is probably best described as your inherent features which to greater or lesser extents are observable by others. Examples may be your gender, race, age etc. Because some of these features are easily identifiable, they often serve as the basis for both positive polices and discriminatory practices when set against a wider group that form the majority. Even for those features which may be less visible (such as some common disabilities), you are still at the mercy of policies that are not designed for you and have no chance of being so unless you make the difficult choice of disclosure.

- Personal self: like many parents with young kids I often feel as if I run parallel lives – diving in and out of meetings to attend school events and doing the mandatory clothing check to ensure there is no kid’s cereal on it before leaving the house. Many of us have relationships with friends, family, our pets etc that, at least for me, keep us grounded. We also have views on our personal attributes and how we think about ourselves (I’m kind, I’m helpful, I’m a hard worker etc). This sense of self-branding is important as it affects how we see the world and how the world might see us.

- Doing self: whether it be that you are a Liverpool fan, a volunteer at a homeless shelter, C-suite level (or all three), for better or for worse, society places currency on understanding what you do with your time. It is interesting that the weight of that currency often depends on whether or not individuals participate in traditionally defined workplaces or do something exciting (where’s an entrepreneur when you need one?). It is the lived experiences of individuals that count; the skills that you have accumulated in your journey regardless of the route taken. We need to be better at embracing the value of those who do not neatly fit into the corporate workplace box.

- Thinking self: focuses on often less visible areas such as your values and beliefs, how you think and your cognitive style. This category includes your religion, political associations and national (or tribal) identity. It can probably be summarised by ‘what I stand for’, ‘how I feel’ and ‘what I think’. This is where cognitive diversity gets most played out and offers the potential to see diversity in a deep way. Some of your beliefs will creep into how you feel about your surface, doing and personal selfs, reinforcing the reflexive and fluid nature of identity.

Feeling perhaps foolishly brave, here’s an example of my own work identity map.

It is worth noting here that no simple sketch could ever fully encapsulate our identity and describe who we are. There is also discretion applied to which aspects of our identity we share with others and which we keep to ourselves.

In filling my identity map, I found myself feeling limited by wanting to say more (what about my love of talk radio?) and wanting to portray myself in the most positive light (did I mention that I’m very very kind?).

But with a few prompts, it did manage to extract some key points about me and got me thinking about the difference between how society views me and how I view myself. This is echoed in Francis Fukuyama’s book Identity which compares extrinsic/societally imposed identity and that which is intrinsically/self-imposed.

Additionally, some aspects of my identity are inherited whereas others have been developed based on my experiences. The map also got me thinking that some aspects of my identity become exaggerated in certain situations. Just think about how you might feel if you were the only Asian person in a room or the only female, or when your minority self was disrespected. In short, the concept of identity is complicated and nuanced, but should be respected as it speaks to who we are.

A framework for employers: integrating identity into people policy

The historical approach of dealing with gender first, ethnicity second, disability third or whichever order suits the corporate agenda has lent itself to box-ticking and compartmentalisation of diversity factors.

Sometimes I feel like a tired mum, a hard worker, a sympathetic friend, an angry citizen, a black woman and/or all of the above. Is it fair for a corporate to tick me off as (i) female and (ii) black and then ignore the rest in a diversity checklist? And where in this model does the diversity of individuals who are white and male fit it?

Filling out my identity map reinforced the inadequacy of any approach which attempts to chop off bite-size identity pieces, and use these as a proxy to understand who I am. This doesn’t mean that corporates should not have initiatives around gender, ethnicity etc. It just means that leadership needs to recognise that these initiatives are only a small part of the whole-of-life employee experience.

The goals of organisations should instead focus on sympathetically combining three things:

- Building a diverse array of people that make up the organisation (this is ‘diversity’)

- Recognising identity (this is ‘respect’), and

- Treating people with decency (this is ‘inclusion’).

Consequently, leading to stronger value propositions for shareholders, employees, clients and wider society.

Diversity is clearly important to organisations. But before we can promote fairness and inclusion in our industry, organisations need a better understanding of who their employees are. One way of achieving this is to engage sensitively with employees and improve knowledge through the use of a framework like the identity map described above. In developing effective I&D policies, sufficient corporate energy should be squarely placed in allowing employees to voice who they are. Otherwise, even the most well-intentioned diversity policies will be destined for failure.

Marisa Hall is a director in the Thinking Ahead Group, an independent research team at Willis Towers Watson and executive to the Thinking Ahead Institute.

As the new program gathers steam, Hitchcock and Berg are turning their focus to other areas of the fund. This includes working with consultant Meketa Investment Group to explore the benefits, and possibility, of simplifying the asset allocation.

As the new program gathers steam, Hitchcock and Berg are turning their focus to other areas of the fund. This includes working with consultant Meketa Investment Group to explore the benefits, and possibility, of simplifying the asset allocation.