On the back of a healthy annual growth rate of well over 20 per cent, last week we welcomed our 500th asset owner signatory.

This is a hugely significant milestone. Asset owners sit at the top of the investment chain, so there is now a powerful collective force committing to further mainstream responsible investment and lead PRI signatories’ $90 trillion in AUM towards more sustainable returns.

Impact on investment managers

Important steps have already been made in this community. Seventy percent of asset owner signatories now actively include ESG criteria in their RFPs to select investment managers. Though a range of approaches exist, our first Leaders’ Group put a spotlight on leading practices in how asset owners select, appoint and monitor their investment managers.

In addition, asset owner signatories tell us that PRI reporting data is useful as part of their evaluation of their investment managers’ activities.

This has clearly had the desired result and gained the attention of more and more managers across the globe. At the launch of the PRI there were more asset owner signatories than investment managers. Today, due to the requirements of many asset owners, over 2,000 investment managers have joined the PRI. In fact, whilst the PRI remains an asset owner-led organisation, investment manager signatories now represent over 70 per cent of the signatory base, and more than 50 per cent of the AUM of the Willis Towers Watson top 500 investment managers globally.

Geographically diverse

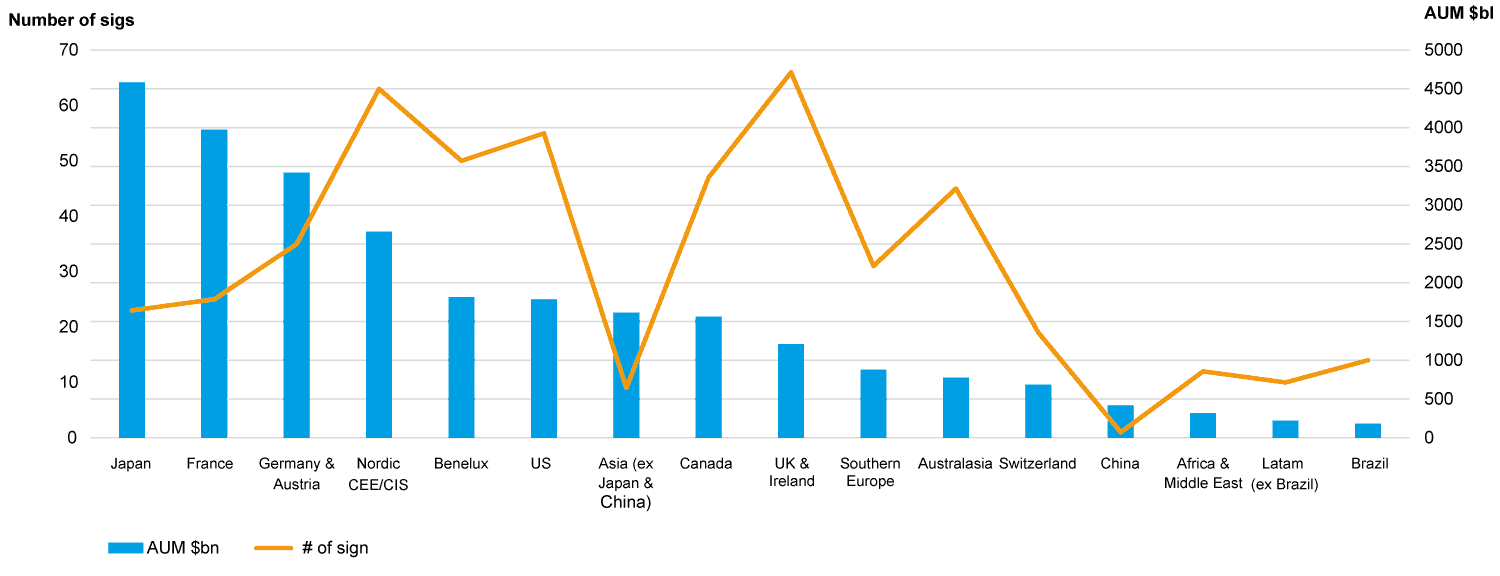

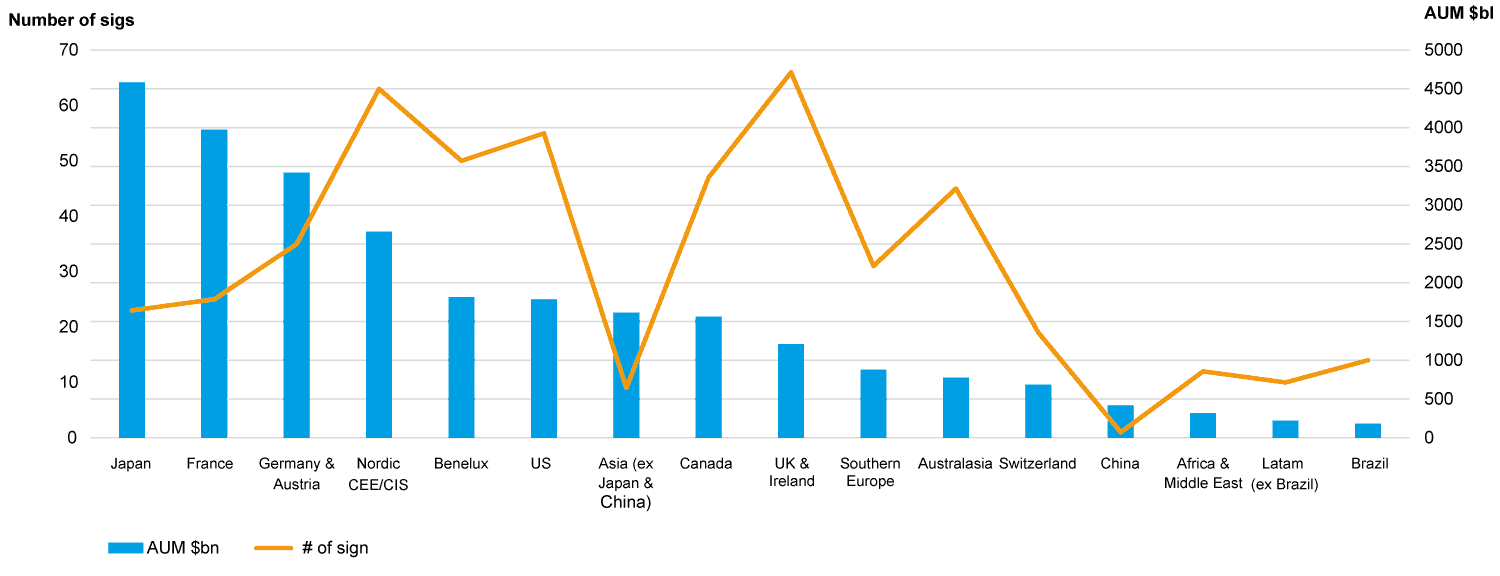

Growth in numbers has also been accompanied by increasing geographic diversity. Our 500th asset owner is Protección SA, a corporate pension fund based in Colombia, reaffirming how responsible investment is now inarguably global. In fact, the largest asset owners at the PRI by AUM are based in Japan, France, Germany and Austria. Our largest amount of asset owners are based in the Nordics, the US and the UK/Ireland.

Asset owners by AUM and size

More recently, the PRI has seen significant growth in markets with a traditionally lower presence, such as Latin America, Southern Europe and Asia. Some of Asia’s big asset owners – Japan Post Insurance, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Ping An Insurance Group (China) and the Employee Provident Fund (Malaysia) – are all new signatories.

It’s not just about pension funds

It’s not just about pension funds

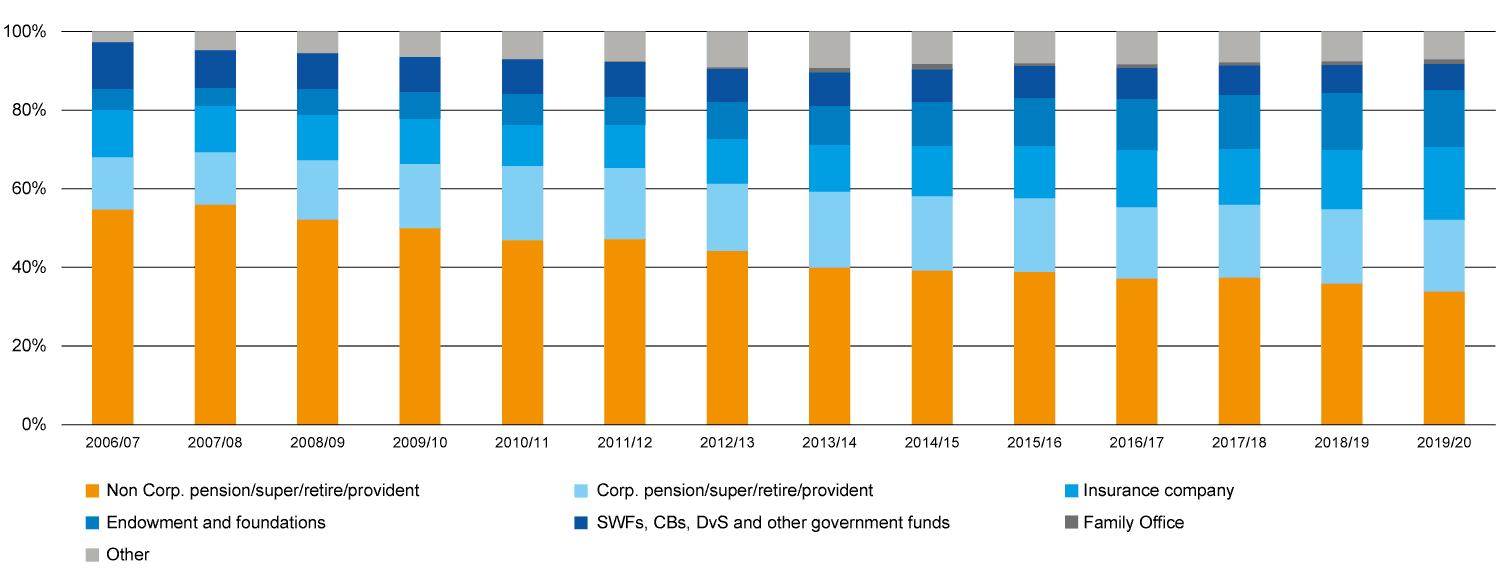

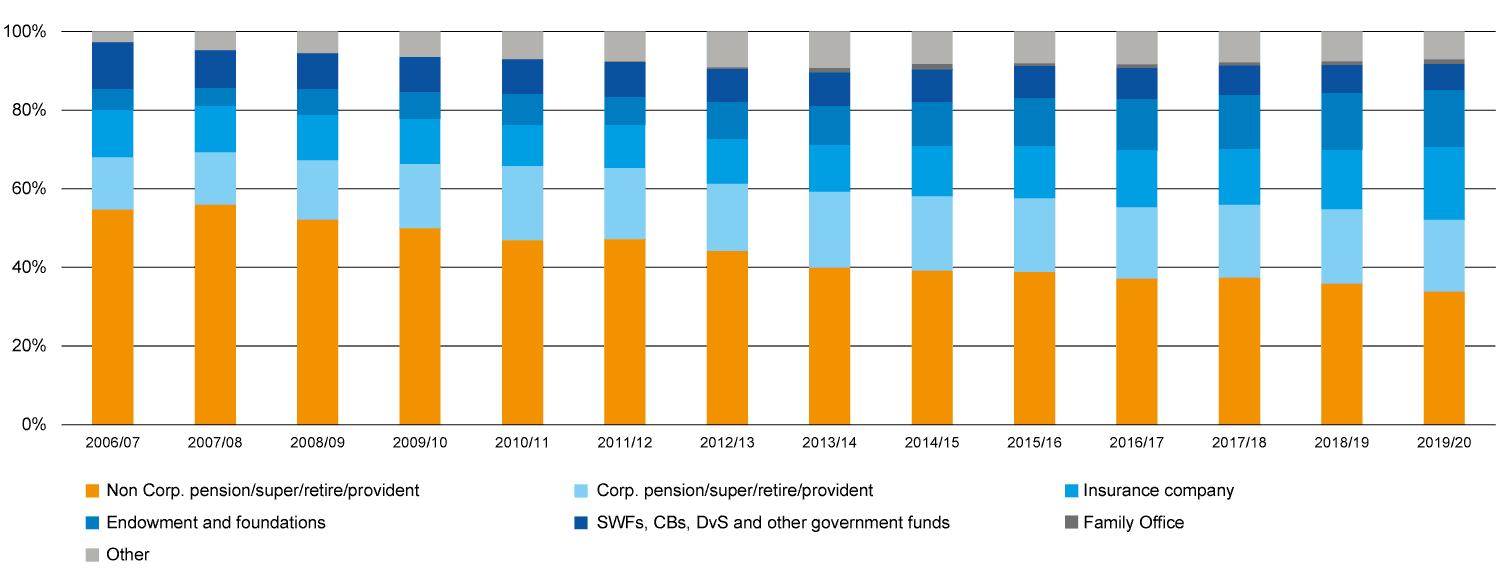

In 2005, the PRI’s founding signatories primarily came from the world’s largest public pension funds. Though public pension funds continue to be the largest group of asset owners, other types of institutional investors are increasingly demonstrating their commitment to responsible investment by signing the Principles.

For example, over 30 insurers became signatories in 2019. In Europe large players like Talanx Group (Germany), Poste Vita (Italy), and Ageas (Belgium) joined. In Asia, Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Sumitomo Life Insurance Company (Japan) and Ping An Insurance (China) also signed up. The PRI’s first US insurer – Re-Insurance Group of America – has also joined.

Endowments and foundations are another growing category, especially in the UK and North America. They now represent around a third of asset owner signatories in North America. PRI signatories now include the Harvard University Endowment, University of Toronto, University of Manchester, London School of Economics and Political Science, and University of Tokyo, whose interest in RI is often driven by student activism on sustainability.

Governments are also recognising the role capital markets must play in promoting social and environment goals. The EU’s Action Plan on Sustainable Finance is maybe the most visible example of this trend. This is spilling over to activity at sovereign wealth funds, central banks and DFIs; in 2019 our first central bank members, De Nederlandsche Bank in Holland and the Bank of Finland joined the PRI.

Working together in a decade of action

Working together in a decade of action

The UN’s calls for a “decade of action” should be a stark reminder of the urgent need for asset owners to step up their responsible investment efforts. And the PRI’s 10-year Blueprint puts asset owners at the heart of our response to key sustainability issues.

How do we support asset owner signatories? Since inception we have released practical guides and tailored tools to help asset owners invest responsibly. In our recent signatory survey, 84% of asset owners agree that these resources are useful in meeting PRI Principles I and II.

The PRI’s asset owner resources

We have released a number of introductory guides for asset owners, with the Introduction to responsible investment for asset owners at the forefront. Other introductory guides include discussions on what responsible investment is; introducing a responsible investment policy and process; and asset class-specific guides on fixed income; listed equity; and private equity.

In 2020 we will be releasing three separate guides on selection, appointment and monitoring of external managers, as well as useful tools to underpin these practices, building on existing resources such as the RI review tool for trustees.

A full list of asset owner material can be found at unpri.org/asset-owners.

Asset owners can also use the Data Portal to monitor and assess their managers, if they are PRI signatories, on a range of ESG issues.

Improving internal processes is one important step. But another is taking collective action. For leading asset owners, there are collaborative initiatives such as Climate Action 100+ (CA100+) and the recently launched UN Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance. Members of the CA100+ include over 430 PRI signatories, of which 225 are asset owners. Here leading asset owners such as the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) in Japan, Aegon, Allianz SE, AXA Group, ABP, Generali Group, Ping An Insurance Group, Aargauische Pensionskasse (APK) and CalPERS are looking to drive change on climate across their portfolios. The UN Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance takes this one step further with a focus on aligning portfolios to net zero by 2050 – clearly a key goal in the light of our climate change crisis.

We would like to thank all the 500 asset owners who have now joined the PRI and whose collective ambition is driving responsible investment forwards. There is still so much to achieve, but there is power in numbers, so let’s roll up our sleeves and move forwards together.

Lorenzo Saa is chief signatory relations officer at PRI.

It’s not just about pension funds

It’s not just about pension funds Working together in a decade of action

Working together in a decade of action