In 2018, sustainable investing worldwide eclipsed $30 trillion in assets under management, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, with $12 trillion originating in the United States.

In the recent market downturn Morningstar’s Jon Hale says that mutual funds that integrate environmental, social or governance (ESG) factors registered record growth in the first quarter of 2020, beating the previous record in Q4 2019.

Clearly, sustainable investing is no longer on the margins, it’s gone mainstream in a big way.

With this in mind it is important to look at the research that is behind the investments, and the funds, and the different approaches taken to analysing data.

The battle between man and machine, that has played out in various arenas – such as Garry Kasporov versus IBM’s Big Blue, and when IBM’s supercomputer Watson out-dueled Jeopardy champions Ken Jennings and Brian Rutter – is now taking place in sustainability research.

Arguably the two leaders from each side of the global market for corporate sustainability research and ratings are Sustainalytics, now owned by Morningstar, which represents the analyst-based sustainability research and ratings approach; and Truvalue Labs, which harnesses AI, machine learning and natural language processing (big data) to provide investors and companies with corporate sustainability performance insights and assessments.

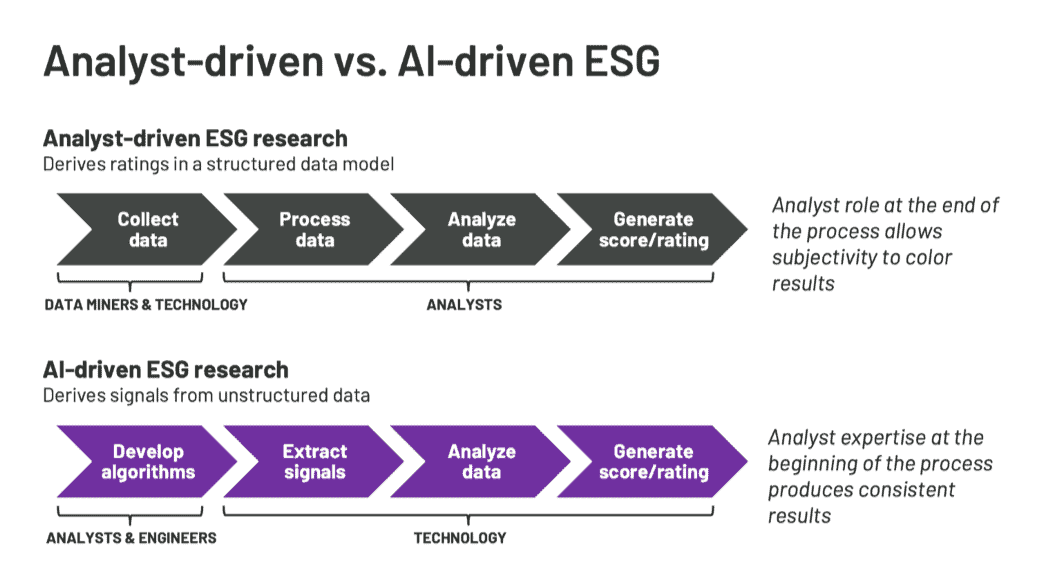

The differences between Sustainalytics and Truvalue Labs’ methodology are depicted below.

About the machine: Truvalue Labs

Al Gore, former Vice President and co-founder and chair of Generation Investment, said “The sustainability revolution is powered by new digital tools. It has the magnitude of the industrial revolution and the speed of the technology revolution. It is the single largest investment opportunity in all of history.”

Truvalue Labs, has harnessed those digital tools, and applies AI to uncover opportunities and risks hidden in massive volumes of unstructured data, including ESG behavior that can have a material impact on company value. It also integrates SASB’s materiality guidelines, which is the gold standard for investors seeking to evaluate a company’s performance from a financial materiality prism.

“The world is awash in unstructured data,” wrote Thomas Kuh, head of index at Truvalue Labs. “Roughly 90 per cent of the data in the world was generated over the last two years alone.”

This super-abundance of unstructured information provides an important source for ESG signals and makes it imperative to incorporate an outside-in view of ESG data to complement companies’ inside-out reporting.

As such, Truvalue Labs made the strategic decision to exclude from its analysis a company’s self-produced ESG information in order to obtain an unvarnished impression of companies’ performance.

“Many sustainable investors are skeptical of AI and the idea that we can trust machines. We make a point of emphasising that the role of AI is to do things humans can’t do efficiently in order to make humans work smarter. And good AI depends on being deployed intelligently by humans. Not all AI is created equal,” Kuh said.

Truvalue Labs’ sustainability performance assessments take into account the sentiments of a wide array of corporate stakeholders. Its coverage of ESG research and ratings spans more than 16,000 companies and it applies its proprietary, customizable AI algorithms to more than 100,000 sources.

An example of the value add it can produce is its coronavirus ESG monitor.

The analyst-based approach

Sustainalytics, a globally recognised provider of ESG ratings and research, has 25 years of experience covering more than 40,000 companies on hundreds of ESG performance indicators. Its 650 employees provide sustainability ratings for more than 20,000 companies that can be customised to clients’ specifications.

Last month Morningstar acquired Sustainalytics for an estimated EUR170 million.

“Modern investors are demanding ESG data, research, ratings and solutions in order to make informed, meaningful investment decisions. From climate change to supply-chain practices, the nature of the investment process is evolving and shining a spotlight on demand for stakeholder capitalism. Whether assessing the durability of a company’s economic moat or the stability of its credit rating, this is the future of long-term investing,” said Morningstar’s chief executive Kunal Kapoor.

Morningstar and Sustainalytics have worked together to provide investors and companies with new ESG analytics, including: the industry’s first sustainability rating for funds, based on Sustainalytics’ ESG ratings; a global sustainability index family; and sustainable investing analytics that includes carbon metrics and controversial product involvement data.

Implications for corporates and investors

Warren Buffet said famously several years ago: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently.”

Today, with the proliferation of social media, a company’s reputation can be bolstered or tarnished in a matter of seconds. Against this backdrop, what are savvy investors and corporations to do to prepare for the new normal?

Truvalue Labs’ AI approach provides several advantages:

- AI reduces the potential for ESG analyst biases to tilt assessments and ratings.

- AI can be applied to more companies more quickly, while analyst-based ESG information is generally updated quarterly or even annually, depending on the provider.

- Because Truvalue Labs’ AI does not rely on self-reported data, it is not as constrained by uneven availability of company-provided data.

Sustainalytics’ analyst-based approach provides its own advantages:

- It enhances company’s disclosed ESG information with third-party insights.

- Experienced analysts can provide invaluable judgement on a company’s culture and trends over time.

- A company’s ESG information can be validated by an assurance provider to enhance accuracy and reliability.

The optimal future state: Best-of-both approach

So which approach works best today? I believe the truth, as with most things, is in the middle. What works best in today’s market is a side-by-side comparison between analyst-based research and ratings such as those from Sustainalytics alongside AI technology from Truvalue Labs.

My bet, however, is that within the next 24 months, the machine will again prevail over the human touch and AI will become the industry standard for assessing a corporation’s sustainability performance and impacts.

This will, in turn, have broad implications for the future of corporate sustainability reporting and performance measurement. It’s indeed a brave new world.

Mark Tulay is the founder and chief executive of Sustainability Risk Advisors