Sharan Burrow general secretary of the ITUC and Paddy Crumlin, president of the International Transport Workers’ Federation outline the recently released baseline expectations for asset managers on fundamental labour rights and why pension funds should be holding their managers to account.

Despite the enormous growth in responsible investment and interest in ESG, there is a looming sense that the global financial system is not serving the wider interests of society and is undermining efforts to build sustainable and inclusive economies. This failure has been acutely felt by workers around the world who are facing attacks on their fundamental labour rights, deteriorating working conditions, and a declining share of the income pie.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), between 2004 and 2017, the share of global income earned by workers declined from 53.7 per cent to 51.4 per cent. On fundamental labour rights, the 2022 Global Rights Index, highlights a series of worrisome trends: this past year, 113 countries excluded workers from their right to establish or join a trade union; the right to strike was violated in 87 per cent of countries surveyed; and trade unionists were killed in 13 countries. These are the worst results reported since the Global Rights Index was first published nine years ago and they are occurring against a backdrop of declining trade union density and collective bargaining coverage in recent decades.

The global attack on fundamental labour rights alongside pervasive economic inequality underscores the urgency for greater investor attention and action to address the “S” in “ESG”.

investor Guidance on labour rights

But, while there are roadmaps for investors to track progress on climate change, there is very little investor guidance in the area of labour rights.

Asset owners struggle to meaningfully evaluate their asset managers’ policies and practices in this area and yet those same asset managers often have significant ownership stakes in publicly listed companies and private assets where workers’ rights abuses are occurring.

Imagine if the world’s largest global asset managers used their sizeable influence to address workers’ rights abuses in publicly listed companies like Amazon.com and Teleperformance, or similar labour issues in private market assets like Cadent Gas in the UK or DIAM Group’s operations in Turkey?

This is what the Global Unions’ Committee on Workers’ Capital (CWC) has set out to achieve, mobilising its global network of trade unions and pension fund trustees to hold global asset managers accountable on workers’ rights.

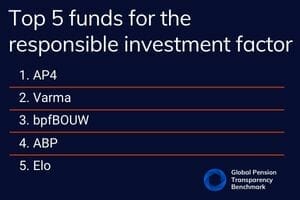

Through the CWC’s Asset Manager Accountability Initiative, pension fund trustees and staff from over 40 pension funds in countries such as Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK, Switzerland, Canada and the USA, are engaging with the likes of BlackRock, State Street Global Advisors, UBS Asset Management and Macquarie.

These engagements provide an opportunity for asset owner clients to express their expectations that the asset managers that aggregate workers’ capital use their influence to drive better outcomes for workers whose rights are being violated.

These engagements are guided by a set of baseline expectations for asset managers on fundamental labour rights, that draw from the ILO Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights.

The Baseline Expectations provide the roadmap on labour rights that has been missing for investors, outlining expectations in four areas: overall stewardship framework; public equities (including proxy voting and engagement); private markets (including stewardship of infrastructure and real estate assets); and policy advocacy.

The CWC is using the Baseline Expectations to steer ESG discussions with global asset managers towards real-world impacts for workers – beyond mere box-ticking and ESG marketing.

Let us now see if, five years down the road, we can pen another op-ed and report that the asset management industry is responding decisively to worker rights violations in their investments.

In the meantime, the CWC will continue to mobilise asset owners to hold their asset managers to account on fundamental labour rights in ESG stewardship policies and practices.

Click here to view the CWC Baseline Expectations

Sharan Burrow is the general secretary of the ITUC and Paddy Crumlin is president of the International Transport Workers’ Federation.