The UK’s £45.3 billion defined contribution pension scheme NEST is conducting a strategic review of its private markets allocation, in a bid to ensure it is still well-positioned in the market since it launched the program back in 2020 to capture a liquidity premium for its young member base.

The analysis by the investor’s eight-person private markets team includes assessing if there are more rigorous ways of identifying opportunities and is a chance to add managers if more strategies are needed for the fully outsourced allocation. The process also includes reviewing all managers to ensure that if the team were putting money out today they would select the same partner, explains Rachel Farrell, director of public and private markets in conversation with Top1000funds.com.

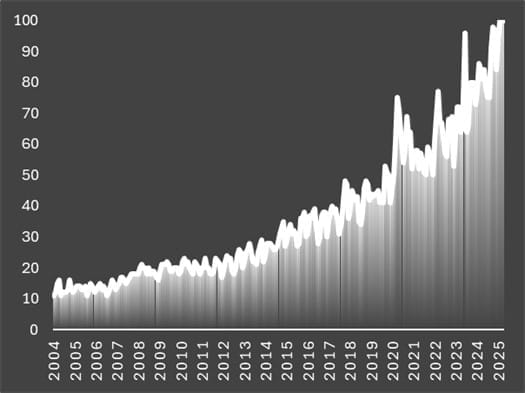

She reflects that one of the biggest challenges for private market investors involves maintaining re-investment and holding onto a deliberate pacing model that is challenged by the rolling maturation of assets as they realise. Something that is made more complicated for NEST by some £500 million ($645 million) of contributions pouring in every month,

“It requires constantly putting more money to work to maintain the allocation,” she says.

NEST’s journey into private markets began by developing some of the first evergreen structures with asset managers to specifically facilitate re-investment. These products have an indefinite life span that supports continuous capital raising, but were uncommon in private markets at that time NEST began building out its allocation, she says.

“The UK market was unused to evergreen structures at the time NEST began investing in private markets, but managers realised the benefits of not having to raise capital all the time. It’s a cost saving that is now accrued to the LP,” she says.

Evergreen structures (and close manager partnerships) also allow the team to constantly monitor deployment, she continues. In closed end structures managers raise the capital, investors commit over a 3-5 year cycle, and although there is communication between the two, the lack of transparency can be a source of investor frustration. In evergreen vehicles, NEST can see its money being put to work and see their investment pipeline.

“In many cases, NEST was the first evergreen fund the manager had done so the structures were really designed in consultation with us.”

NEST began investing in private assets with an inaugural allocation to private credit. That has now grown to include infrastructure, renewables, private equity and real estate and “as long as opportunities continue to present themselves” the pension fund aims to increase its 20 per cent allocation to privates to 30 per cent by 2030.

The team is close to funding a new US direct lending mandate and is also looking at opportunities in value-add infrastructure that marks a departure from the predominantly core allocation. NEST also added a second timber manager in August 2025.

Farrell believes scale also contributes to success. Researching private markets requires resources to monitor and select managers, and NEST’s scale also gives it more negotiating power with managers.

“Scale contributes to success in private markets, and the government’s initiative to create larger pools of capital makes a lot of sense. Financial services benefit from efficiencies of scale, and this is true of DC too,” she says, referencing the government’s Pension Schemes Bill which aims to consolidate smaller DC and DB schemes into fewer, better governed and more scalable entities.

NEST has styled its manager relationships around allocating large amounts to particular partners. It means that in many ways the pension fund has grown with its managers, and the relationships are strategic on both sides. Still, NEST took strategic partnerships one step further when it bought a stake in IFM Investors last year, joining a collective of 15 Australian pension funds.

“Our ownership stake in IFM means we treat each other as part of the same organization – it’s like being inside of the business.”

Close manager relationships also support better terms.

Farrell looks carefully at the trade-off between its large mandates and its own name in the market and wouldn’t work with a manager not willing to offer products at a fee the team feel is justified. Nor does NEST pay performance fees.

“We don’t believe that is necessary,” she says. There is no performance compensation within its own organization, and she says culturally NEST remains unconvinced by the idea that performance pay makes people work harder. Instead, the investor nurtures an ethos characterised by a belief that “people come in and do the best they can because they care about our members and want to do the right thing.”

NEST operates in a target date fund structure whereby members are invested in diversified funds that target their retirement. NEST’s investment structures and strategies have evolved in line with the Australian model

Another component of strategy is governance, of which ensuring managers have an appropriate valuation process as the value of assets grows in the portfolio, is key.

Because it’s a DC plan NEST prices a daily NAV, yet because private markets don’t price daily the team must ensure they are comfortable with the price they are holding assets, she explains. Governance around the valuation process includes ensuring each manager values and refreshes the portfolio and knows NEST will intervene if the valuation is suddenly out of wack because of infrequent valuation.

For example, private markets typically lag the public markets correction trajectory.

“During the pandemic, the correction in private equity lagged behind public equity. Had we been invested in private equity at this time, this would have been an obvious point of intervention. Public markets corrected more quickly than privates, and we would have needed a process with our managers to consider applying a discount, for example,” she says.

Good governance also includes ensuring manager stability. Managers are monitored on a quarterly basis to makes sure the team hasn’t changed in any way that could impact the strategy they manage on NEST’s behalf, particularly given the high level of M&A in fund management means teams often shift

Investing in private markets has also enabled NEST to integrate responsible investment. As direct owners, private markets give investors the ability to be a more active and influential owner; help managers focus on responsible investment and ESG, and have important conversations with companies.

Admittedly, equity owners can wield more influence than debt providers but she concludes that private debt investors can play an important role in encouraging corporate reporting.