The investment office of the $341.3 billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) has revealed that it has shelved any plans to introduce leverage into its portfolios to help improve returns.

The use of leverage was canvassed extensively at the CalPERS Board of Administration meeting in July this year, as it looked for ways to meet return targets and improve its 68 per cent funded ratio. It was believed even then that leverage could have only a marginal impact on both measures.

In an asset liability management (ALM) workshop on November 13, CalPERS managing investment director, asset allocation and risk management, Eric Baggesen, told the board that “after a lot of discussion” the investment office decided not to proceed for two reasons.

“The first reason is the application of leverage, for one thing, certainly increases our market sensitivity,” Baggesen said. “It’s questionable as to whether we would really want to increase our market sensitivity when the majority of the segments of the investment opportunity set appear to be pretty highly valued at this point in time.”

Baggesen said the second, and “probably even more relevant” issue, from the perspective of strategic asset allocation, was that the application of leverage is not a set-and-forget exercise. He said the use and benefit of leverage depends on the spread between the cost of the leverage and the expected benefit of purchasing an asset using that leverage.

“That spread is not a constant, it expands and contracts,” he said. “That expansion and contraction, by definition, appears to recommend leverage as an active-management tool, in contrast to a strategic-management tool.”

Baggesen’s comments on leverage emerged during the CalPERS board’s asset liability workshop, an event held every four years to review, and if necessary revise, the fund’s long-term strategic asset allocation, and the demographic, actuarial, financial and economic assumptions that underpin them.

Four new candidate portfolios

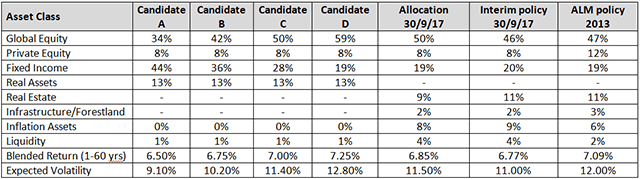

The board was presented with four new candidate portfolios (labelled A to D) the CalPERS investment office has developed. When the board meets in December, it will be asked to select the most appropriate of the four.

Candidate portfolio A is designed for an expected return of 6.5 per cent and that figure increases in increments of 25 basis points with each candidate, finishing at 7.25 percent for portfolio D.

The expected return of each portfolio represents its so-called ‘blended return’: the combination of a short-term (one-year to 10-year) return estimate based on the CalPERS investment office’s projections, and a long-term (11-year to 60-year) expected return, based on actuarial estimates, with an allowance for fees.

The board will need to consider these portfolios in terms of their volatility characteristics, and how the expected return of each portfolio supports the discount rate applied to the fund’s future liabilities.

For example, candidate A’s expected blended return of 6.5 per cent “would require a shift downwards in the discount rate, from 7 per cent; and that [50-basis-point reduction] in the discount rate would, in turn, immediately translate into a reduction in the funded ratio”, from 68 per cent to 64 per cent.

A reduction in the funded ratio would require additional contributions from the fund’s participating employers.

“In the same way, if you pick a portfolio that would increase the discount rate, that would result in an increase in the funded ratio, albeit with a greater degree of equity concentration and volatility that attaches to that,” Baggesen explained.

He said the investment office considers any one of the four candidates to be “implementable and prudent portfolios, although they’re not all equally advisable” given current market valuations.

He said portfolios A, B and D represent “pretty significant shifts in the actual exposure, and the shifts that take place in these candidate portfolios are really evident in the public equity and fixed income lines”.

“Elements such as private equity [are in asset classes attractive enough to] exist at the maximum bound constraint for them, regardless of any portfolio mix we put before you.

“That’s an indication of the degree to which the constraints are a binding issue on this analysis. I would suggest a [close look at] those constraints will be a big part of the mid-point review that takes place in two years’ time. But we believe [they] are rationally established for the present timeframe.”

The candidate portfolios currently have zero exposure to inflation-linked assets, across the board. Baggesen said this reflected “the fact we do not have a clear understanding of the effects of inflation on the liability structure, nor do we understand clearly exactly what risk inflation presents to the fund”.

“We do believe it presents a risk, though,” he said. But he explained there was more work to do on inflation to “restructure what we’re doing in that space to more appropriately align it with the effects on the liability structure.”

The four candidate portfolios’ allocation to liquidity is consistent as well, at 1 per cent across the board.

Baggesen said the fund was able to set a low liquidity target because it anticipated strong cash flows from contributing employers to make up for the impact on its funded ratio of recent underperformance, the reduction in the target rate of return, and general employee pay increases.

The candidate’s parade