The investment outlook over the next few years looks pretty dismal compared with the double-digit returns investors have grown accustomed to over the last decade, so it is critical for asset owners and managers to have a crystal-clear understanding of their clients’ risk appetites.

For the Queensland Government’s top investment adviser, Jim Christensen, that has meant spending countless hours over the last year meeting with stakeholders and ensuring they, themselves, have a clear understanding of their own investment objectives and how much risk they are prepared to take on in a bid to meet them.

“Quite a few of our clients have been served pretty well by their strategy for some time, but the world is different and more challenging now,” Christensen says. “Getting absolute clarity around what a fund’s objectives are and marrying that with the strategy is very important, because if we’re not on the same page, then down the track there are going to be disagreements.”

Christensen concedes it is a “strange conversation” to initiate.

“Because returns over the past decade, the past five years in particular, have been very good, lots of funds with a moderate-to-high risk profile have delivered double-digit returns,” he explains. “But over the next five years, we think returns on these moderate-risk funds are going to be around half that, with a high single-digit return a pretty good outcome.”

QIC began life in 1991 as the Queensland Investment Corporation, tasked with delivering long-term returns to help the state fund its asset liabilities associated with programs such as WorkCover and public servants’ defined-benefit plans, as well as the investment portfolios backing local councils, hospitals and cultural institutions.

Since 2001, the Queensland Government-owned firm has been allowed to take on external mandates, prompting its growth into a major player as a specialist global diversified alternatives house.

Today, QIC has more than A$85 billion ($65 billion) under management on behalf of 110 institutional clients, half of which are from outside the Queensland Government family, including superannuation pension managers based in other states and internationally.

Christensen regards it as a big advantage for QIC that it operates on both the buy and sell side.

“It means that there are more expertise and resources in my team than if we were investing only QIC’s own money,” he says.

The 404-member investment team is growing. In late January, former DMP Asset Management chief executive Allison Hill joined QIC, reporting directly to Christensen, in the newly created role of director of investments for the global multi-asset division. She’ll continue many of the conversations around risk appetite.

As Christensen sees it, asset owners have three options for how they react to the lower-return outlook: ramp up risk, lower their return targets, or come to accept targets may be missed for a number of years. He believes the latter is the only sensible response.

“Most people like to be successful in their objectives, so they either lower their objectives or they take on more risk,” he says. “But the world is genuinely uncertain and you’ve got to ask yourself if it is actually prudent to take on more risk.”

Christensen’s view is that in most cases it is not, but that ultimately depends on the risk profile of the end client.

Most of QIC’s clients have longer-term horizons, which means they can handle some short- to medium-term illiquidity risk, but he is worried about the outlook for the group of smaller clients with a shorter time horizon and mandates that make them unable to withstand capital losses.

Taking the time and effort to ensure expectations around risk are aligned up front makes it easier to

act quickly when markets turn.

“It’s about getting risk levels set at a tolerance that makes sense and setting strategic long-term asset allocation,” Christensen says. “Once we’ve got that in place, there’s a lot of trust there that means we can change managers or allocations, so long as they are within these broad, agreed ranges.”

To date, QIC has not made any major strategic changes to client portfolios and is maintaining risk levels at about their long-term averages.

Homecoming

It is a little over two years now since Christensen returned to QIC to take on the top job as chief investment officer and managing director of its global multi-asset division.

He joined from TelstraSuper, the country’s largest corporate super fund, where he held the role of CIO for six years. Prior to joining TelstraSuper, Christensen had spent more than 12 years at QIC, culminating as managing director of its active-management division.

It has been a happy homecoming for the Queenslander who, from 2010 to 2015, commuted between TelstraSuper’s Melbourne head office and the family home in Brisbane almost weekly.

Christensen couldn’t have been happier when the opportunity came up to lead the investment team at QIC and spend more time with his wife and kids. Such plum positions in the industry are few and far between in the Sunshine State.

While QIC runs as an independent body, being government-owned can bring a perceived pressure to invest in the state of Queensland.

“We get pitched a lot of stuff from folk up here in Queensland, and from all over the world…Having a lot of money to invest means you’re a very popular guy,” Christensen observes. However, he says that while local deals have the advantage of easier due diligence, their financial merits have to stack up.

“You probably know your own back yard a bit better, but you’ve still got to hold it up against the lens of what other stuff is available around the globe,” he says. “Everything needs to justify its place in the portfolio.”

Liquid alternatives

Over a truly long-term horizon, of 20-30 years, Christensen still sees great value in real illiquid assets, although he laments that it is getting harder to find real estate and property deals that look attractive in the short-to-medium term.

One of the main ways QIC has been trying to juice up returns within the agreed-upon risk settings of clients’ strategies is by allocating more to its diversified liquid alternatives funds.

“Tactically, over the past six months, we have been adjusting our exposures to liquid assets in line with our internal dynamic asset allocation processes,” Christensen says. “This has generally meant a slight reduction in equity exposure and an increase in exposures to fixed interest.”

QIC’s approach to building liquid alternatives strategies is to find systematic, factor-based exposures that offer excellent transparency.

Basically, it’s looking for equity-like returns that are largely uncorrelated with equity risk. The strategies are typically long-short funds, although QIC does offer long-only solutions for clients with mandates that preclude shorting.

The systemic risk factors that can be isolated and targeted include quality, value, carry, momentum, trend-following and volatility, across a wide range of liquid markets.

Volatility risk-premia strategies have been favoured recently. As a result, when volatility made a notable return to global markets in late February, the liquid alternatives strategy dipped between 1.5 per cent and 2 per cent, but outperformed global equities, which were down 3.5 per cent to 4 per cent for the month.

This was “broadly in line with expectations”, Christensen says. “The overall strategy has strong risk-control measures that limit the impact of extreme movements in volatility, such as we experienced in February.”

Since its inception, the QIC Liquid Alternatives Fund has generated total returns of about 6 per cent annualised, in line with its objective.

“Within the liquid alternatives strategy, there are a number of specific volatility strategies, which ranged from flat to negative outcomes in February,” Christensen says. “Over time, these strategies have contributed strongly to the fund’s overall performance.”

Liquid alternatives remain only about 5 per cent of QIC’s total portfolio, which is dominated by real assets such as property and infrastructure.

Housing stress

Most of the investment decision-making processes at QIC are run using quantitative models, which indicate that mortgage stress will be, hands down, the biggest threat to the Australian economy and financial markets as interest rates inevitably rise in the years to come, Christensen warns.

“In terms of our doomsday scenarios, they are all linked to things like a housing market crash,” Christensen says. “The level of household debt is high and that’s probably one of the largest concerns we’ve got. If you look at interest payments, compared with what they were pre-GFC, they are relatively low, so there is headroom to stomach some extra interest payments, but everyone should be aware that it is going to happen at some point.”

When rates do rise, Christensen notes, some households won’t cope with their mortgage repayments.

“Some households have been paying down more than the minimum for some time, so will have a buffer, but clearly there are also newer entrants with a lot of debt that will be under stress if marginal rates trickle higher.”

That said, he remains confident that the Reserve Bank of Australia won’t allow a housing bubble collapse.

“Rates will rise at a moderate pace in Australia, while remaining well below historic averages for the foreseeable future,” he predicts. “The increase in rates will invariably have a negative impact on the sector, but the moderate backup in yields means this is manageable.”

Eye on China

The macroeconomic risks Christensen worries more about, in terms of the likelihood of them happening, all come from China.

“In Australia, we are very much linked to China’s fortunes,” he says.

QIC’s quant team is focused on monitoring the risks of a hard landing for China’s slowing growth, and Christensen visits China at least once a year to “get a feel” for things on the ground.

“I was in China in August last year, and the mood was generally positive on the outlook from the locals,” Christensen says. “On China, we have a broadly consensus view that growth is moderating in line with government forecasts, but will remain healthy and supportive of global economic activity.”

For QIC, one of the advantages of being a state-owned entity is the entrée it provides into the international sovereign wealth fund community.

This includes an ongoing dialogue, and some co-investments, with the roughly $US1 trillion ($1.3 trillion)

China Investment Corporation, although Christensen remains tight-lipped on the specifics of that relationship.

“We’ve got good relationships with a number of government funds around the world, but particularly up in Asia,” he says. “They’ve got a much deeper insight into what’s happening in China than we will have.”

Another benefit of working with sovereign wealth funds is the opportunity to learn from how they manage the challenges that come with massive scale.

“Some of these organisations have hundreds of billions, or even trillions, of dollars and there are all sorts of challenges that come with putting that sort of money to work.”

A clear head for the long run

QIC has 10 offices around the world, with staff working out of: Brisbane; Sydney; Melbourne; New York; Los Angeles; Cleveland, Ohio; San Francisco; Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; London and Copenhagen.

When Christensen isn’t travelling, members of the QIC investment team know that if they want to talk to him about an idea, they can always join him on his daily run along the Brisbane River.

“If people want to find me, they can come for a run with me at lunchtime,” Christensen says. “I like to run most days. So, it irritates me if I can’t get out for 6-8 kilometres.”

He credits the running with helping him keep a clear, calm head.

“Markets will do unpredictable things,” he says. “And if you’ve been around long enough, you’ll realise that…because you can’t be jumping at shadows.”

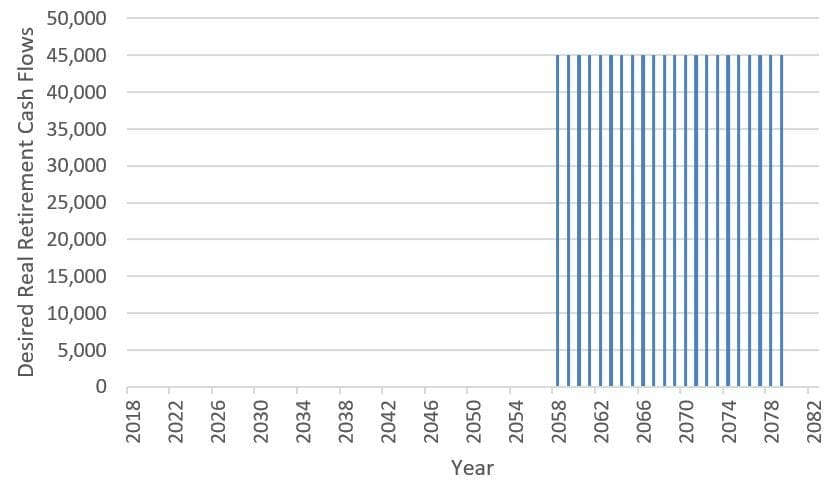

Chart 1: Potential desired retirement cash flows for a 25-year old Australian

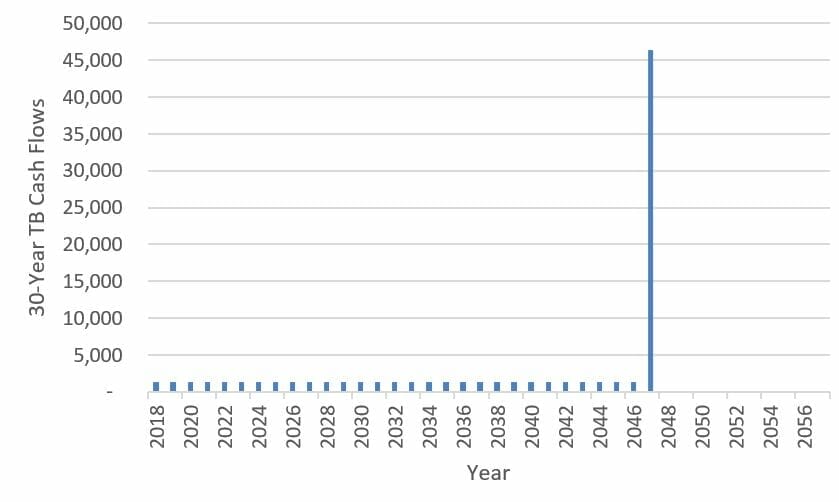

Chart 1: Potential desired retirement cash flows for a 25-year old Australian Chart 2: Cash flows from a traditional, nominal 20-year TB (with a 3% annual coupon)

Chart 2: Cash flows from a traditional, nominal 20-year TB (with a 3% annual coupon)