Executives from 75 companies representing all 50 states, with a combined market value of $2.5 trillion and employing more than one million people, came together last month as part of the LEAD on Carbon Pricing effort to urge the US Congress to pass meaningful climate legislation.

Ceres and our partners convened the largest group of businesses calling for climate legislation in at least a decade. Their message was loud and clear: Congress must put forward policy responses equal to the severity of the climate crisis including a national price on carbon.

A cascade of new scientific findings and economic research shows the increasingly devastating impacts of climate change on the economy and on communities. The latest National Climate Assessment explains that, even with adaptation measures, climate change is likely to cause $800 billion in damages. Without strong action, that number could rise to as high as $3.6 trillion.

An analysis by Trucost shows that operating margins will turn negative for 46 per cent of companies in the chemicals sector by 2030, because emitting carbon will become too expensive. In the US, climate change could lead to as much as $160 billion in lost wages, as two billion labour hours will be lost annually by 2090 due to temperature extremes.

As study after study has made clear, ignoring climate science means accepting enormous economic risks. We must act now to reduce emissions and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

A well-designed price on carbon is widely considered an essential component of the efforts necessary to meet the climate crisis. The goal of a price on carbon is to address a market failure: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have global costs that are currently not borne by the emitter. A carbon price puts a monetary value on those emissions to account for their real social costs, which helps to drive down emissions across the economy.

Investors, companies and the people they serve rely on functioning supply chains, operations, and distribution facilities—and climate change poses significant threats to these elements essential for a profitable business.

Companies recognize this threat and are taking action to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon future by investing in renewable energy and setting GHG reduction targets. However, they cannot tackle to problem without policy solutions from Congress.

An economy-wide price on carbon would create a level playing field as these companies work to protect themselves against the financial risks of climate changes, by allowing companies to decide for themselves the best approach to reducing emissions.

Furthermore, a meaningful national price on carbon would provide the policy certainty investors and companies need to make long-term operational and investment decisions in the United States. As Tim Smith, director of environmental, social and governance (ESG) shareowner engagement at Walden Asset Management, puts it:

Investors are increasingly aware of the dangers of climate change and its impact on companies and our portfolios. We have seen a flood of papers and statements in the last six months, from BlackRock to the Bank of England to our Fed, calling for urgent action. Companies and investors working together have a central role in implementing climate solutions. A price on carbon would create the market signals needed to drive clean energy investments, grow the job market and strengthen the American economy. It is a critical tool in US efforts to address climate change.

Investors and companies agree on the need to implement a national price on carbon. Beyond the 75 investors and companies that gathered on Capitol Hill last month, 415 investors from around the globe—many based in the US and together representing over $32 trillion in assets under management—have called on governments around the world to step up action to tackle climate change, including a meaningful price on carbon.

And, it’s not just the private sector that supports a price on carbon. A March 2018 Gallup poll of registered voters found that 71 per cent of respondents favour a carbon tax on fossil fuel companies and support using the revenue to reduce other taxes.

At last, congressional leaders are hearing the call to act on the climate crisis. More than 80 congressional offices on both sides of the aisle and in both chambers took the time to meet with investors and companies participating in LEAD on Carbon Pricing. Lawmakers and their staffers heard the resounding message on the urgency of the climate challenge and the need for a strong policy response from the federal government.

Now, we need Congress to do more than listen. They must act.

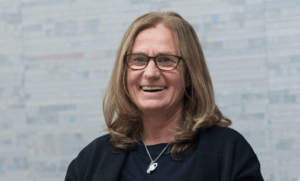

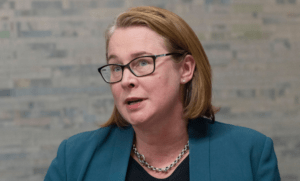

Anne Kelly is the vice president of government relations at Ceres, a sustainability nonprofit organization working with the most influential investors and companies to build leadership and drive solutions throughout the economy.