Investors are putting pressure on companies to accelerate the shift to purpose-driven leadership and focus on human capital policies during the crisis. But while there are some examples of corporations making policy changes that positively impact their workers, supply chain issues pose a significant problem.

Purpose-driven leadership and stakeholder capitalism are in the spotlight during the coronavirus-induced health and economic crisis, with investors urging the business community to focus on human capital management during this humanitarian crisis.

More than 286 long-term institutional investors representing $8.2 trillion have signed the investor statement on coronavirus response calling on the business community to hone their human capital policies and focus on paid leave, prioritise health and safety, maintain employment, maintain supplier/customer relationships and financial prudence.

Dave Zellner, chief investment officer of Wespath and one of the signatories, says the short-term decisions made by corporations over the months to address this crisis will play a crucial role in defining the speed and nature of the economic recovery.

“We believe this presents a unique opportunity for businesses to demonstrate their commitment to workers, contractors, and the broader global community,” he says.

The statement is a call to action on business to look after their workers and Wespath says there is already evidence of good business practice.

“We publicly commended Google for supporting small businesses and non-profits through its contribution to a relief fund established by the City of Kirkland and the Kirkland Chamber of Commerce, which was the location of the initial outbreak of the virus in the US,” Zellner says.

Just Capital is tracking how corporate America is treating its stakeholders and has produced a COVID-19 corporate response tracker which looks at the largest 100 companies’ policies and practices in response to the pandemic. The tracker looks at policies such as adjusted hours of operations, paid sick leave, supply chain impacts and financial assistance.

For example in response to the crisis Walmart, which is the largest employer in the US with more than 1.5 million workers, has added 11 of the 18 policies measured by Just Capital.

The tracker also showcases corporate leadership and since measuring it on March 24 the number of executive pay cuts has more than quadrupled from 6 per cent to 27 per cent. Some include the Disney board which is taking a 100 per cent pay cut (Bob Iger, chair of Disney, had a total compensation of $47.5 million in the most recent financial year) and the company chief executive , Bob Chapek, who is taking a 50 per cent pay cut. At Boeing the CEO, Dave Calhoun and chair, Larry Kellner will both forgo all pay until the end of the year.

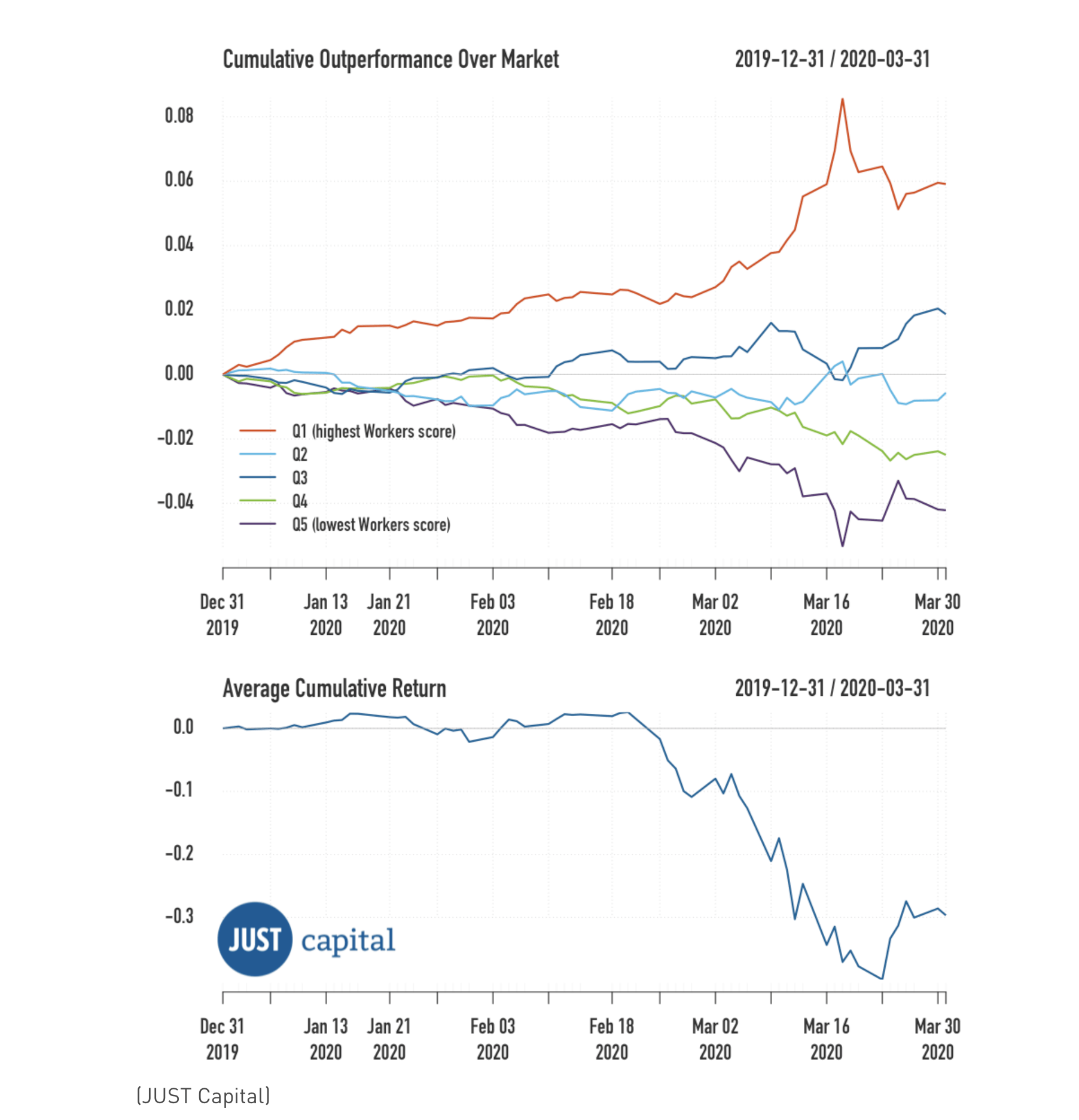

Importantly Just Capital reports that the companies that have been supporting their workers have been outperforming their peers during the crisis. Companies that are demonstrating leadership and caring for their employees’ health and safety will be better positioned for the long term, it says.

Truvalue Labs, which uses AI to analyse the impact of the coronavirus crisis on ESG issues for companies, has produced a “response signal” that it says could be a helpful tool in identifying new investment opportunities. The signal shows among other things the industries that have stepped up their operational response to the crisis, and Truvalue Labs says the companies leading the charge in these industries could have under-appreciated intangible value.

Not all good news

But while there are some examples of corporations making changes to policies to positively impact their workers, supply chain issues pose a significant problem.

The global garment value chain is one example of the potential deep and sustained impact the crisis could have on millions of workers. The combination of widespread retail closures, layoffs and furloughs, mandated factory shutdowns and slowing consumer demand has resulted in the cancellation of orders through the value chain and left some suppliers unable to pay workers. The impact of this is particularly pertinent in emerging countries. In response to this employers, unions and major brands together with the International Labour Organsiation have signed a call for action to support the garment industry.

The signatories have agreed to work with governments and financial institutions to mobilise sufficient funding to enable business continuity among manufacturers so wages can be paid.

General secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation, Sharan Burrow, says emergency funds are needed to protect workers.

“We cannot afford the human and economic devastation of the collapse of our global supply chains and millions more in developing economies thrown back into poverty,” she says. “Jobs, incomes and social protection are the dividends of business continuity and this statement calls for emergency funds and social protection for workers to guarantee industry survival in the poorest of our countries. Leadership and cooperation from all stakeholders are vital to realise a future based on resilience and decent work.”

Wespath’s Zellner says fair labour practices are an important element of achieving its sustainable economy framework which also includes supporting strong local communities.

“Corporations have an important role to play in supporting local communities,” he says. “It is in this spirit that Wespath has signed on to the Investor Statement for Coronavirus Response.”

In mid-March, Wespath responded to the outbreak by transitioning the vast majority of employees to a remote, work-from-home model. Moreover, it regularly provides workers with updates from senior leadership about the benefits available to employees including paid time off flexibilities, employee assistance programs to support mental wellness and information regarding federal COVID-19 legislation.

It also supports the local community by coordinating an employee-giving campaign for healthcare workers at local hospitals, first responders, and other frontline workers.

“We urge companies, banks and investors to come together to help position the economy for a quicker recovery, that is sustainable over the long term,” Zellner says. “Wespath’s experience investing for over 100 years as a steward of investment assets has meant we have weathered many crises as an institution. This perspective has informed our focus as a fiduciary on long-term, sustainable growth and our belief in the sustainable global economy.”