Key takeaways:

- Failure to address climate change will have severe economic and social repercussions.

- Pressure for a just transition, a systemic and ‘whole of economy’ approach to sustainability, is growing.

- The human causes of climate change are now firmly established, but the human response, and impacts, are still very much to be determined.

Climate change is a human issue. There is now scientific consensus that the greenhouse-gas emissions causing climate change are predominantly man-made. This means that climate change is unequivocally a human issue – as a society, we can influence the course of that change, by adapting our individual and collective behavior. There are, of course, many uncertainties about the potential impacts of climate change but the choices that we make also add to this uncertainty.

Failure to address climate change will have economic and social repercussions. Global action, or indeed inaction, will affect the global workforce, human wellbeing, and society at large. No one expects these impacts to be equally distributed; some estimate that 75% of climate change damage may affect developing countries, despite the poorest half of the world’s population contributing to just 10% of global carbon emissions.1

The Role of the Just Transition

The phrase ‘just transition’ refers to the balancing of these interests: addressing the environmental risks that climate change presents, while ensuring that workers and communities are not left behind, and that the ‘green’ solutions deployed do not carry an ugly human cost. As a society, how we address this complex and increasingly politicized issue will be a considerable challenge in the coming years.

The ILO (International Labor Organization) defines just transition as “… a bridge from where we are today to a future where all jobs are green and decent, poverty is eradicated, and communities are thriving and resilient. More precisely, it is a systemic and whole-of-economy approach to sustainability.”2

The role of the just transition, and questions of fairness and equity, also have the capacity to undermine attempts to meet the Paris Agreement on climate change. The transition to a low-carbon economy could not only lead to ‘stranded assets’ but also ‘stranded workers’ and ‘stranded communities’. Higher levels of social trust enable institutions to undertake policy reforms that are in the general long-term interests of society. Where there is no societal buy-in, there are often adverse impacts on the overall impacts that policies seek to achieve. This can have significant economic and human costs too, as was seen with the gilets jaunes (‘yellow vest’) protests in central Paris. These started in late 2018 over substantial fuel-tax increases to tackle climate change and the resulting impact on lower-income workers.

What Does This Mean in Practice?

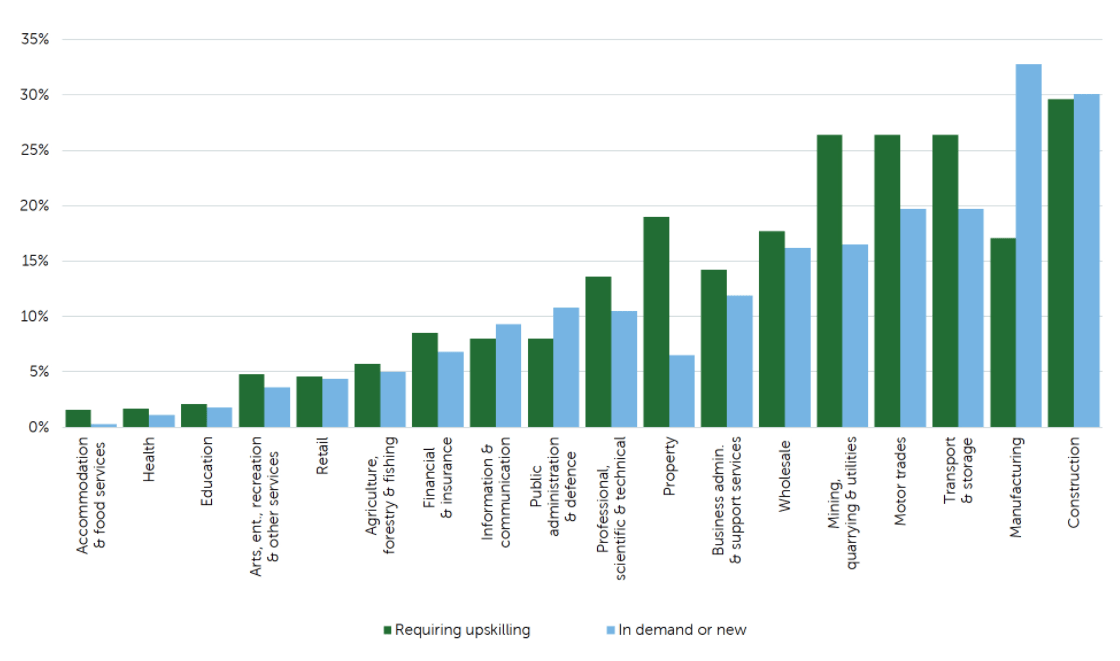

A key requirement of addressing climate change is changing our energy system, and reducing the use of fossil fuels. Understandably, workers in fossil fuel-related industries may feel vulnerable and oppose the changes that threaten their jobs, livelihoods and communities, as we have seen within the European Union. Taking the UK as an example, it is estimated that one in five UK workers could be affected by climate change – 10% of jobs may have less demand, and 10% may have more, with significant changes in structural employment. There will also be changes in the types and locations of jobs across and within these economic sectors.

Employment Implications of the Transition on Different Sectors in the UK

An additional challenge is that these impacts will often be concentrated in specific communities reliant on industry, and new employment opportunities may not be created in these regions. Some workers may easily adapt – an engineer at an oil and gas company may be well suited to being an engineer at a renewables company. But not all skills are transferable. For example, it is estimated that the north of the UK may see 28,000 direct job losses resulting from the closure of coal-fired power plants alone.3 In less clear-cut cases, there will need to be research and investigation to understand the net impact of jobs, in order to manage this.4 Subsequently, there will be the need to generate new jobs in regions affected and to retrain and reskill workers.

Moreover, the transition is not just away from fossil fuels but also towards renewables. We need to consider the social implications of renewables technology, construction and operations as their role in our energy system increases. There have been numerous allegations of human-rights abuses at renewables companies, primarily related to project construction, ranging from intimidation, to indigenous rights and land-rights disputes. More recently, we have also seen this with increasing scrutiny over the use of forced labor of minorities in solar industry supply chains. This is material for our transition to a lower-carbon society: for those whose human rights have been adversely affected, and also for investors, as project delays and cancellations can have financial consequences. With increasing discussions of mandatory human rights due diligence requirements, this is only likely to become more salient.

The human causes of climate change are now firmly established, but the human response, and impacts, are still very much to be determined. There are no silver-bullet solutions, nor is there clear responsibility for any single actor. For example, who should be accountable for the reskilling of employees, and who should bear this cost? As always, collaborative action between all stakeholders – governments, corporates, investors, NGOs (non-governmental organizations), trade unions, and employees – would be ideal. But what does this mean in practice? And how can this collaboration be facilitated? It is clear that this will not be a simple task, nor one that any single stakeholder can achieve individually. It is a deeply political, cultural and social challenge, but it is a challenge which must be addressed as we continue to shape the way climate change develops, and the human impacts it will have.

Sources

Important information and disclosures

Important Information

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that strategy holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

This is a financial promotion. Issued by Newton Investment Management Limited, The Bank of New York Mellon Centre, 160 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4LA. Newton Investment Management Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN and is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation. ‘Newton’ and/or ‘Newton Investment Management’ brand refers to Newton Investment Management Limited. Newton is registered in England No. 01371973. VAT registration number GB: 577 7181 95. Newton is registered with the SEC as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Newton’s investment business is described in Form ADV, Part 1 and 2, which can be obtained from the SEC.gov website or obtained upon request. Material in this publication is for general information only. The opinions expressed in this document are those of Newton and should not be construed as investment advice or recommendations for any purchase or sale of any specific security or commodity. Certain information contained herein is based on outside sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. You should consult your advisor to determine whether any particular investment strategy is appropriate. This material is for institutional investors only.

Personnel of certain of our BNY Mellon affiliates may act as: (i) registered representatives of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation (in its capacity as a registered broker-dealer) to offer securities, (ii) officers of the Bank of New York Mellon (a New York chartered bank) to offer bank-maintained collective investment funds, and (iii) Associated Persons of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation (in its capacity as a registered investment adviser) to offer separately managed accounts managed by BNY Mellon Investment Management firms, including Newton and (iv) representatives of Newton Americas, a Division of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation, U.S. Distributor of Newton Investment Management Limited.

Unless you are notified to the contrary, the products and services mentioned are not insured by the FDIC (or by any governmental entity) and are not guaranteed by or obligations of The Bank of New York or any of its affiliates. The Bank of New York assumes no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the above data and disclaims all expressed or implied warranties in connection therewith. © 2020 The Bank of New York Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

In Canada, Newton Investment Management Limited is availing itself of the International Adviser Exemption (IAE) in the following Provinces: Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec and the foreign commodity trading advisor exemption in Ontario. The IAE is in compliance with National Instrument 31-103, Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations.