The ratio of working years to retirement years should be a minimum of 2 to 1, says David Knox, senior partner at Mercer and author of the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index, who says increasing the pension age is a universal policy solution to the pension crisis.

He points to the Netherlands as an example of best practice in this regard. An increase in the target retirement age there is automatically triggered by any increase in life expectancy, as determined by the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics. From January 1, 2018, the target retirement age for occupational plans in that country will increase from 67 to 68.

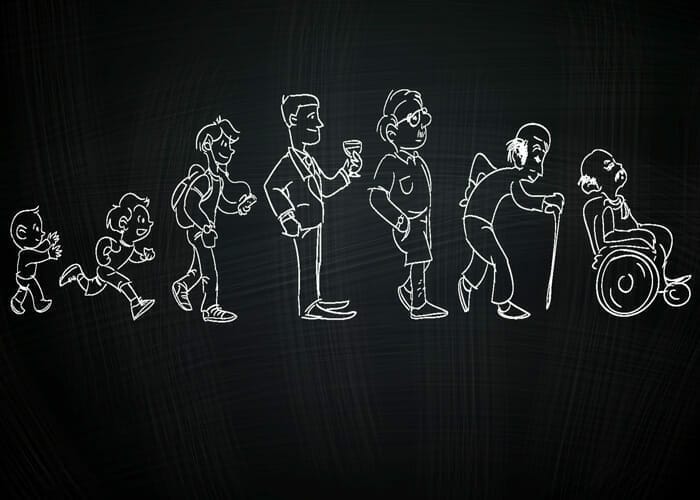

“If you live to age 95 but retirement is at 65, sustainability of the system is under pressure,” he says. “You will be in retirement for 30 years but you wouldn’t have worked 60 years to support that.

“In the old days, when people retired at 65 they would die at age 75, that ratio was more like 4 to 1. The ratio of working to retirement years shouldn’t be less than 2 to 1, preferably a bit more.”

Unchanged for 100 years

In Australia, as in many countries, the retirement age has gone unchanged for more than 100 years. The pension age was set at 65 in 1909 and was not changed until 2009 when the Rudd government announced it would be increased to 67 by 2023.

Knox says increasing the pension age adds to the sustainability of a system, but also adds to the awareness people have of working longer because they are living longer.

The Mercer pension index compares the retirement income systems in 30 countries, using more than 40 indicators that benchmark each country’s system. The index uses three sub-indices as metrics: adequacy, which accounts for 40 per cent of the index score; sustainability (35 per cent); and integrity (25 per cent). The Australian system ranks third, behind Denmark and the Netherlands.

Knox says many of the challenges relating to ageing populations are similar around the world, irrespective of a country’s social, political, historical or economic circumstances.

He says the policy reforms needed to alleviate these challenges are also similar. In addition to increasing the pension age, he suggests encouraging people to work longer, addressing the level of funding set aside for retirement, and employing benefit design that can reduce leakage of benefits before retirement.

Denmark, Netherlands, Australia lead pack

Denmark, the Netherlands and Australia – in that order – ranked as the best pension systems in the ninth Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index. No countries received an ‘A’ rating this year, with Denmark, the Netherlands and Australia scoring a ‘B+’.

This is a slip for Denmark and the Netherlands, which have previously received the top score. Their lower score is due to the inclusion of real economic growth in the sustainability sub-index.

There is a huge disparity in systems around the world, as reflected by the scores. Argentina ranked last, scoring 38.8, and top-ranked Denmark scored 78.9.

The top three countries all scored well across all three sub-indices, while some countries, such as France, scored well in a particular category (80.4 for adequacy, which was the top score) but were let down by other categories (38.6 for sustainability and 55.8 for integrity).

Knox says the scores highlight weaknesses in the systems and areas for reform. He points to Austria, Brazil, Italy and Japan as countries that must tackle pension reform sooner rather than later.

Ninth Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index country rankings