Common sense must be applied to statistical data and rules-based investing should only be adopted with caution. Investors should prepare for the inevitable moment when the game suddenly changes.

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

Yogi Berra

In the aftermath of the financial crisis a growing sense of unease with mechanical rules-based investing techniques emerged, following the destruction of value in the portfolios of many carry managers, technical traders, arbitrageurs and quantitative stock pickers (among others).

However, in recent years, investor appetite for mechanical techniques has returned, with much excited discussion of “factor investing”, “smart beta” and “volatility control”. It is therefore reasonable to ask: can we invest by rules?

While financial markets have existed for hundreds of years, our understanding of market dynamics, and especially market crises, is surprisingly limited.

You would obviously be overly wishful in your thinking if you approached a meteorologist and asked them to create a model of hurricane formation based on the experience of one single hurricane. Luckily for meteorologists, in 2008 to 2009 there were 28 hurricanes, with the scramble for unused names reaching such underseen fare (in the English language world) as Fausto and Odile.

Fortunately for investors, financial hurricanes occur much less frequently than natural-world hurricanes, with few investors today having seen more than a dozen serious market crises in their working life. How can we hope to derive rules that might be robust in stressed market conditions based on a small sample of such experiences?

Prudish Victorians who were keen to avoid recounting the gory details of human reproduction often used to tell their children that babies were delivered by storks.

Just over 10 years ago a group of German academics “proved” that this idea had merit. They noted using statistical techniques that there was a strong correlation between the population levels of storks in and around Berlin with the number of home births.

They hadn’t lost their minds, they were merely keen to demonstrate the dangers of relying too heavily on statistical data without engaging common sense.

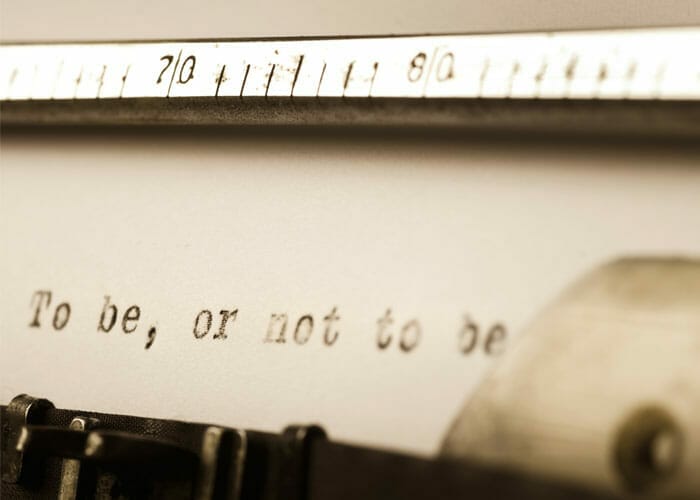

How often is common sense jettisoned in the world of financial theory with the notorious backtest? The “infinite monkey theory” holds that a monkey with a typewriter, given a sufficient length of time, will write out the complete works of William Shakespeare, even though they are hitting the keys of the typewriter randomly.

Given a large or infinite amount of monkeys this happens much more readily.

The point is that, by overwhelming likelihood, as soon as the monkey has written the last line of The Two Noble Kinsmen, what follows will be gibberish.

Similarly, with hundreds of researchers around the globe seeking to climb the academic ladder by finding apparently successful trading rules (or “factors”), investors must be careful to avoid relying on patterns that may prove no more persistent than the monkey that has apparently reproduced the works of Shakespeare.

The problem any investor faces is that they sit like a player at a board game, playing chess; but then the game changes and it’s snakes and ladders; once more and it’s backgammon; again, and it’s Monopoly.

Simply relying on how things were is at best of limited use: patterns emerge, are recognised, and disappear; systems emerge, are useful, and then their usefulness fades. Rules-based investors should prepare for the inevitable moment when the market “rules” suddenly change.

So while investors should be cautious when adopting rules-based approaches involving limited oversight, we are not arguing that all investment rules are worthless. Indeed, some time-tested heuristics include:

- Don’t put all your eggs in one basket (diversification), and don’t rely on the same basket manufacturer (counterparty diversification).

- Regularly rebalance portfolios in order to maintain a target allocation (in line with desired risk tolerance) and generate a modest rebalancing premium.

- Seek to be contrarian: “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” (Warren Buffett).

We might therefore conclude that rules, in and of themselves, are neither good nor bad; but it is important to understand the shortcomings of rules-based approaches and to distinguish between rules that are likely to be helpful and those that are not. Some sensible questions to consider when evaluating rules-based strategies include:

- Is there empirical support over long time periods, across regions and market regimes, that the strategy is robust to minor variations in rule definitions?

- Is there out-of-sample support? That is, has the rule continued to “work” after the publication of results, or has the effect been arbitraged away or proved to be a figment of data mining?

- Is there an intuitive economic or behavioural explanation for the historical success of a given rule and a reason to believe that this effect will persist in the future?

- Who is responsible for monitoring the ongoing efficacy of a given rules-based approach?

Rules can work, but we prefer rules-based approaches that are time-tested, are supported by a robust argument and where there is the possibility of evolution over time to reflect the changing rules of the game.

Matthew Scott and Phil Edwards work for Mercer.